Summer 2003

Punch cuts

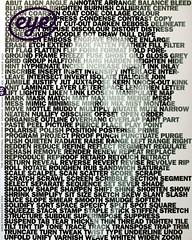

The type and layout of a Victorian weekly anticipated Modernism

No culture or era is a monolith; the Victorian epic was packed with sub-plots. Yet time can flush out diversity, and the common received notion of Victorian design quickly conjures a Retro image of eclectic hyperdecoration. The opposite is also true. Beyond the poster, the title page, and the exotic foundry specimen, everyday Victorian typography was smart, generic and utterly of its time.

The page layout of Punch magazine, a work of precise, elegant restraint, persisted from the magazine’s founding in 1841 for almost a hundred years, the only change being an increase in text size in the 1890s. Very classic, practically indestructible and perfectly Modern.

Its form was the culmination of a period of radical typographic modernisation in London, beginning around 1800 and notable for the emergence, by the mid 1830s, of a spectacular variety of new type genres from the foundries of Thorne, Figgins, Caslon et al: fat face, Egyptian, sans serif, 3D and so on.

During these years, the Didot (Modern) style replaced the old styles, killing off the long ‘s’, ‘ct’ and ‘st’ ligatures, and non-lining figures, while weight contrast became the new way to create interest in one’s typographic layout, outmoding the traditional oppositions of roman versus italic and caps versus lowercase.

Art history places the Modern movement during the early twentieth century, and type history follows suit, chronicling the emergence of the sans serif in the late 1920s as a Bauhaus-branded expression of reductive functionalism. In this scheme of things great store is set upon the sequence ‘Realism; Modernism; Post-Modernism’, making it impossible to accept the original sans serif faces (and other contemporary typographic experiments in pure plastic formalism) as expressions of Modernism, concurrent as they are with realist painting, and preceding the invention of photography.

Nonetheless, Vincent Figgins beat Paul Renner (Futura) to the punch by a century. The evidence could not be clearer: his 1836 specimen shows a bold sans serif, spelling out the word ‘modern’. The Caslon & Livermore 1837 specimen contains fifteen pages of bold condensed, all-cap, sans serif faces; William Caslon IV had shown the first sans [serif face] 21 years earlier.

Renner discussed the concept of the Modern, and how it is a process rather than the style of a particular era, but it’s unlikely that Figgins or Caslon theorised about such stuff. They just did it. The Crystal Palace (1851) was a piece of engineering, far removed from architecture or art. The fine arts carried the heavy intellectual load; decoration added merit to applied art; and nothing could be further off the map than the naked shape of letters. There were no design trade journals, no critics to ask: ‘Dude, where’s the lower case?’ T. C. Hansard, in his monumental Typographia (1826) devoted but a handful of paragraphs to the aesthetics of type design, mainly to roundly slate the latest ‘Monstrosities!!! … the book printing of the present day is disgraced by a mixture of fat, lean and heterogeneous types, which to the eye of taste is truly disgusting,’ with a nod to the burgeoning market for job printing, ‘ … for which purpose it appears so appropriate …’ Hansard attributed the trend entirely to the capriciousness of typefounders; we recognise a cultural ecology in the marketplace, where all are both shapers and shaped.

The innovative type founders of this era were contemporaries of Henry Maudslay, who improved the slide rule and built the first precision lathe (called the ‘mother tool of the industrial age’ by Witold Rybczynski in One Good Turn). The modern style of type was not so much an imitation of the sparkle of engraved lettering, but an expression of every designer-engineer-craftsman’s quest for finesse.

These graphic changes did not happen in isolation, but were part and parcel of the general turmoil that accompanied the birth of the modern industrial state. In politics, the suffrage crisis (only three per cent of men with the vote) had put the Britain on the brink of armed rebellion prior to the Great Reform Bill of 1832, which redesigned the structure of society. New lifestyles emerged in the 1830s with the advent of mass transit by rail and bus. Turner expressed the modernism of this age in his 1844 painting Rain, Steam, and Speed; Figgins expressed it in his conceptual type designs; and Bradbury & Evans, Printers, Whitefriars, expressed it with Punch.

Nick Shinn, type designer, Toronto

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.