Autumn 1992

Quentin Fiore: Massaging the message

The man who gave form to Marshall McLuhan’s ‘global village’ designed books that were both for and ahead of their time

A recent article on the critical reception of Marshall McLuhan’s work summarily dismissed his 1967 The Medium is the Massage and 1968 War and Peace in the Global Village as ‘crude publicity tracts’. Yet for many designers, these books are landmarks in modern book design. This divided appraisal reveals the gap that persists in publishing between words and pictures, high academia and low mass media, and authors and designers. Massage and War and Peace are remarkable for momentarily blurring the professional, commercial and formal distinctions that publishing is built upon.

The Massage book was initiated by Quentin Fiore, who was at the time a successful graphic designer and communications consultant, and who is now living near Princeton, New Jersey. When we met to discuss the work he did with McLuhan, I was surprised to learn that it was less of a collaboration than I had imagined: it seems more accurate instead of describe Fiore as a graphic interpreter of McLuhan. While McLuhan approved each page of the book – revising only one word – all the texts and images, their order and arrangement, were controlled by Fiore. He and McLuhan are listed as co-authors; Jerome Agel, a friend of Fiore’s and a pioneer book packager, is listed as ‘co-ordinator’ of the project. It was Agel who served as the link between Fiore and McLuhan, and who later organised the follow-up book.

Fiore described The Medium is the Massage as having ‘no “original” manuscript. The idea was to select some of McLuhan’s ideas from previous publications and present them in isolated ‘patches’ on individual spreads with accompanying artwork.’ The major sources for the book were McLuhan’s 1962 Gutenberg Galaxy and 1964 Understanding Media, the two texts that were gaining him notoriety for their aphoristic style and unqualified assertions. The Massage book was, at its core, an attempt to popularise McLuhan, just as McLuhan himself had done in articles for Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, TV Guide, Mademoiselle, Family Circle, Glamour, McCall’s, Look, Playboy and the Saturday Evening Post. To succeed, Fiore felt the book ‘had to convey the spirit, the populist outcry of the time, in an appropriate form. The “linearity” of the average book wouldn’t work. The medium, after all, was the message!’

While Fiore gave McLuhan’s ideas their most popular and visual form, McLuhan was already an accessible writer. Gutenberg Galaxy has chapter glosses that read like advertising headlines (‘Nobody ever made a grammatical error in a non-literate society’), while Understanding Media is divided into 33 essays that average three to four pages in length. Complaining to a friend about his 1951 The Mechanical Bride, McLuhan wrote that the editors ‘are obsessed with the old monoplane, monolinear narrative and exposition’. McLuhan disliked writing, and the brevity of his chapters reflects his impatience with the medium: he preferred the impact of the bon mot and the punchline to the intricate discourse of the classic academic. Popularisation was part of McLuhan’s agenda from the outset.

Despite McLuhan’s fame at the time, the project was difficult for Agel to sell. After being rejected by 17 publishers, a deal was finally struck with Bantam, who agreed to produce 35,000 copies in paperback, while Random House did a larger hardbound edition. The rapid success of the book led to two more runs of 35,000, followed by German, Portuguese, Spanish, Japanese and Italian editions which brought its worldwide circulation close to a million. The Medium is the Massage became McLuhan’s largest-selling publication, a fact which irritated him.

The success of the project was all the more surprising considering the conditions under which it was produced: Fiore was given a limited budget and a three-week deadline for design and production. Composed of commissioned photographs as well as stock images of news events and personalities, the book is a hybrid: part book, part magazine, part storyboard. It combines short prose passages with caption-length texts, some tied directly to images, others demanding to be read more obliquely – Fiore’s visual punning is as persistent as McLuhan’s wordplay. Showing a remarkable lack of confidence, the publishers demanded that the work not push editorial or production boundaries too far: ‘There was concern that the book meet with wide acceptance. The publishers felt that the anticipated sales would not warrant expenditures for colour, die-cutting, or photo-studio “tricks”.’ Thus from both an editorial and production standpoint, Fiore felt that the project was not ambitious enough.

The most striking aspect of The Medium is the Massage, however, is the way it explores the space of the book – its literal scale and sequential unfolding – as part of its content. For instance, the full-bleed images that introduce an idea on one spread are repeated on the following spread at postage stamp size. This structure, repeated across several pages, encourages the images to be read differently according to their scale and juxtaposition to other images and words. Fiore’s layouts destabilise the traditional hierarchy of image and caption, text and illustration. Elsewhere, Fiore highlights the literal dimension of the book with a spread showing the thumbs of the reader holding the pages open: a photographic doubling of the reader’s own hands.

While the typography suggests a cool Swiss-Modern sensibility, the photography bears the trace of a more diverse heritage, stretching from Moholy-Nagy’s Painting, Photography, Film and the Dada collages of Heartfield and Hausmann to the underground publications of the 1960s. Fiore cites as precedents such influences as Marinetti, Wyndham Lewis, concrete poetry, Apollinaire’s calligrammes, Fluxus, rebuses, and the ‘mouse’s tail’ of type in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

Fiore is a self-taught designer. His only visual education came from a short period of painting and drawing classes in New York in the late 1930s with George Grosz and, later, Hans Hoffmann. His classmates under Hoffmann included Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock; while studying with Grosz, he witnessed the teacher dismiss fellow student Paul Rand for bringing frivolous coloured pastels to class. Hitchhiking across the country with a letter of reference from Grosz to Moholy-Nagy, Fiore attended the New Bauhaus in Chicago. His departure was swift – ‘I wanted to paint pictures, not design furniture!’ – and after moving back to New York, he found himself working proficiently and profitably as a lettering artist, primarily for the emerging ‘Midwestern Modernist’ Lester Beall.

As phototypesetting technology displaced hand-lettering, Fiore shifted from lettering artist to graphic designer. During the late 1940s, he worked as an art director for Christian Dior and Bonwit Teller. From the 1950s he worked as a graphic designer for organisations such as the Ford Foundation, Time-Life, RCA and Bell Laboratories. His professional work included magazine design, instructional films, signage and consultation on an electronic newspaper. While remembered for his collaboration with McLuhan on the fringes of publishing, he was at the same time firmly positioned within the mainstream of graphic design, working at an advanced level for large, basically conservative organisations. When asked whether he considers himself a classicist or a Modernist, Fiore says the term ‘vaudevillian’ is more apt, since he did whatever was required of him at the time. A good deal of his work is classical and, as he says, ‘even reactionary’, bearing the influence of his two great passions: the Renaissance and illuminated manuscripts.

The design of The Medium is the Massage is both inventive and readerly. Fiore remembers it being attacked by the publishing world for having too few words per page, and for lacking a preface or table of contents. At the time, Fiore was told that ‘truly serious books should bulk at least an inch and three quarters’. The people in the ‘industry of the word’, as Fiore describes publishing, ‘demanded words – lots of words – all set on good, grey pages’. For people in publishing and traditional book design, The Medium is the Massage was threatening: ‘The reaction of those designers with a highly developed moralistic sense was that the book was “manipulative”.’ As to its popular reception, Fiore feels that ‘the Massage book became a kind of icon for many people. The images, the feel of the book, summed up their time. It became a graphic expression, and an approbation of their feelings and thoughts. Along with the general acceptance of the book, however, there was some hostility: it promoted illiteracy, encouraged drug use, it corrupted the morals of the American youth, it was anti-intellectual, and so on.’

The success of The Medium is the Massage led to a number of spin-off projects with McLuhan and Agel. One was an audio version of Massage with McLuhan, Fiore and Agel doing vocals to a blend of audio effects and music. Fiore dismisses the record as a silly by-product of an otherwise important project. Another book began as a compilation of McLuhan’s writing on automation. The 1967 manuscript, edited by Agel and Fiore, was entitled Keep in Touch. The project was scheduled for publication by Bantam, but after McLuhan underwent a massive operation to remove a brain tumour, he cancelled the book and instead offered Agel, Fiore and Bantam the manuscript for War and Peace in the Global Village.

In McLuhan fashion, War and Peace is a collage of thoughts about generational division, the ‘new tribalism’ of electronic technology, and the ravages of violence and war. With the exception of his membership of the Canadian pro-life movement in the 1970s, McLuhan did not take up explicit political positions, and thus the mode of commentary in War and Peace is oblique rather than specific: for example, a news photograph of a soldier, probably in Vietnam, is accompanied by the headline ‘Every new technology necessitates a new war’. Critical passages are softened by gentle humour: an image of the Pentagon is caption ‘The biggest filing cabinet in the world’. Formally, the book is more conventional than The Medium is the Massage. According to Fiore, McLuhan submitted an official manuscript, which ‘created a devotional relationship to the text among the publishers and editors’. Fiore describes the relationship between author and designer, and between text and image, as more traditional than in the first book, ultimately limiting the scope of his influence on the final product.

Two other book projects, both published in 1970, bear the stamp of Fiore’s involvement. Do It! Scenarios of the Revolution, written by the Yippie leader Jerry Rubin and designed by Fiore, was an anti-authoritarian, free-love, blow-dope manifesto given lively form through the use of images from underground comics and news photographs. Fiore was invited to design the book by Rubin himself, who, along with Abbie Hoffman and Timothy Leary, was taken with his work with McLuhan. Rubin was one of the infamous Chicago Seven, responsible for the organisation of the demonstrations during the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. According to Fiore, Rubin collected much of the visual material in the book: “We would lay out the book in my office on weekends when he was free to fly in from Chicago, where he was on trial in Federal Court.”

The jacket copy for the book, published by Simon & Schuster describes Rubin’s text as the “most important political statement made by a white revolutionary today”. The Federal conspiracy trial gave the book a special cachet, as did the introduction by Black Panther leader-in-exile Eldridge Cleaver. Like War and Peace, Do It! has a more traditionally conceived relationship between texts and images, though the images – such as the photo-collage “Fuck Amerika” and the frequency of nude insurrectionists – remain startling, the document of another era. When asked whether his association with Rubin caused him any professional problems, Fiore describes himself as living a double life. With a few exceptions, his work with Rubin, McLuhan, and, later Buckminster Fuller, made no contact with the refined classicism and Modernism of his work with more conventionally-minded clients.

Perhaps Fiore’s most unusual project was a collaboration with Jerome Agel and Buckminster Fuller. Echoing the success of The Medium is the Massage, the 1970 I Seem To Be a Verb became Fuller’s biggest seller. Like the McLuhan book, it served as a general introduction to a study of the environment, focusing (loosely) on technology rather than on media. The first few spreads have a traditional orientation, but the pages are soon divided horizontally along a central axis, with the lower half printed upside down in green ink. Across the centre of each spread, a quote from Fuller, which continues throughout the entire book, is conveyed in a telegraphic line of large caps. When the quote reaches the end of the book, it turns and loops back, continuing in the opposite direction. The pages themselves resemble a scrapbook, crammed with advertisements, newspaper clippings, paintings, camp film stills, lyrics, wire-service photographs, and quotes set in contrasting typefaces. I Seem To Be a Verb is even less linear and didactic than The Medium is the Massage, and seems to revel in its puzzling discontinuity, mixing the words of Charlie Brown and Charles de Gaulle, the images of Hollywood and starving children. The quote from Fuller is the only apparent thread holding things together.

Common to all Fiore’s books is the deliberate repetition of images and texts. This technique seems partly inspired by the serial forms of Pop Art, but more fundamentally, repetition is an effect of the mass media which McLuhan sought to explain. Throughout his career, McLuhan described his work as a series of “probes”. Bruce Powers, one of McLuhan’s collaborators, has written that these “probes” were conducted not through argument, but with a “semantic wedge” – for example, the phrase “the medium is the message”. According to Powers, a wedge such as “the medium is the message” allowed McLuhan to shift attention from content to form. Fiore complements this “semantic wedge” with a design strategy centred on repetition, reinforcing the large premise of McLuhan’s work that America is a culture of reproduction.

Jean Baudrillard has noted the relationship between McLuhan’s “medium message” and Walter Benjamin’s landmark 1936 “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”. As Baudrillard writes in “Symbolic Exchange and Death”: “Benjamin (and later McLuhan) grasped technique not as productive force (where Marxist analysis remains trapped) but as medium, as the form and principle of a whole new generation of meaning.” Thus Benjamin and McLuhan both draw attention to reproduction, not as a neutral product, but as a definitive aspect of modern culture.

Fiore’s books recycle, repeat and make patterns out of images and texts: the ability to create meaning and pattern by altering the scale and context of images and texts constitutes Fiore’s graphic response to McLuhan. Yet this McLuhanesque strategy has informed Fiore’s work with Rubin and Fuller as well, appropriately, since these authors too are concerned with the reproduction of social life (Fuller’s liberating technologies or Rubin’s critique of oppressive institutions).

Fiore finds irony in the fact that his 50-year career is measured by work he produced on the sidelines during a span of two-and-a-half years. In retrospect, the late 1960s has emerged as one of the most interesting moments in American history, a period of re-evaluation and re-invention that affected design as strongly as it affected politics. The Fiore books laid a foundation for a design practice that merges design and writing, form and content, theory and practice. The fact that this strategy has been rarely repeated says more about the conservatism of the “industry of the word” than about the success of the projects. Occasional exceptions, such as the 1990 photo-text book Artificial Nature, edited and designed by Jeffrey Deitch and Dan Friedman, reveal the viability of designer-writer collaborations. But the same enthusiastic merging of theory and populism and words and pictures forged by McLuhan and Fiore has not been repeated.

J. Abbott Miller, Partner, Design Writing Research

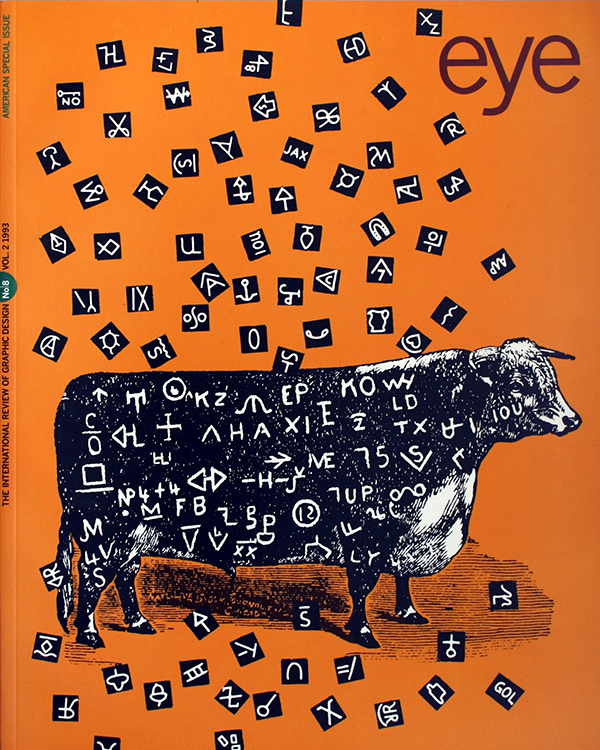

First published in Eye no. 8 vol. 2, 1993

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.