Autumn 2018

Radical platform

From its early grassroots days, Spare Rib provided a groundbreaking public arena for women’s issues, opinions and feelings that had previously been sidelined

The first issue of Spare Rib was published in July 1972, launched by founding editors Marsha Rowe and Rosie Boycott, with designers Sally Doust and Kate Hepburn. Rowe and Boycott announced their goals with a manifesto that declared: ‘The concept of Women’s Liberation is widely misunderstood, feared and ridiculed. Many women remain isolated and unhappy.’ With the new magazine they pledged to reach women across ‘material, economic and class barriers’. In sharp contrast to existing women’s magazines in both form and content, Spare Rib provided a new platform that addressed issues – from sexual and racial equality to household tips, child- and healthcare – within a radical, contemporary framework strung through with wit and criticism.

The design of Spare Rib was crucial to its aims. Rowe later wrote that it had to ‘look like a woman’s magazine, yet with contents that did not reflect the conformist stereotyping of women. It had to suggest the familiarity of women’s magazines – like a good friend, intimate, loyal, supportive – while also being challenging, questioning, exciting and radical.’

Doust and Rowe first met when they both worked at Vogue Australia (as part of a mainly female team) in the late 1960s. Rowe had also been a secretary at the Australian underground magazine Oz (1963-69). Upon moving to the UK, Rowe worked with the London incarnation of Oz, but soon found the male-dominated scene of the underground press ‘disillusioning’, both for the sexist elements of its output and a reluctance to advance women’s careers beyond administrative roles.

Rowe found inspiration in the takeover of the New York-based underground newspaper RAT by the feminist groups Redstockings and Weatherwomen, as well as the guerrilla theatre group Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell (W.I.T.C.H.), who renamed the title Women’s LibeRATion.

The designers used paste-up methods (‘Lick and stick’) to produce camera-ready artwork for London litho printer J. H. Paull. Type was set by T&R filmsetters who provided galley setting, which Doust and Hepburn pasted up on grids of two, three or four columns using Cow Gum. Spare Rib was saddle-stitched (bound using staples), with its news pages – sent later than the features and other elements – printed on coloured paper with coloured ink, using a different combination of colours for each monthly issue. For photography and illustration, Doust and Hepburn drew on a large number of friends, many of them fellow students from Central School of Art & Design and the Royal College of Art. These included photographer Angela Phillips, illustrator Posy Simmons and cartoonist Deborah Allard and – controversially – several male contributors, including Bob Mazzer, Michael Foreman and Peter Brookes (see Eye 93).

Spare Rib no. 9, March 1973. Design and layout: Kate Hepburn, Rose Verney, Lucinda Cowell and Sally Doust. Cover photograph by Roger Perry.

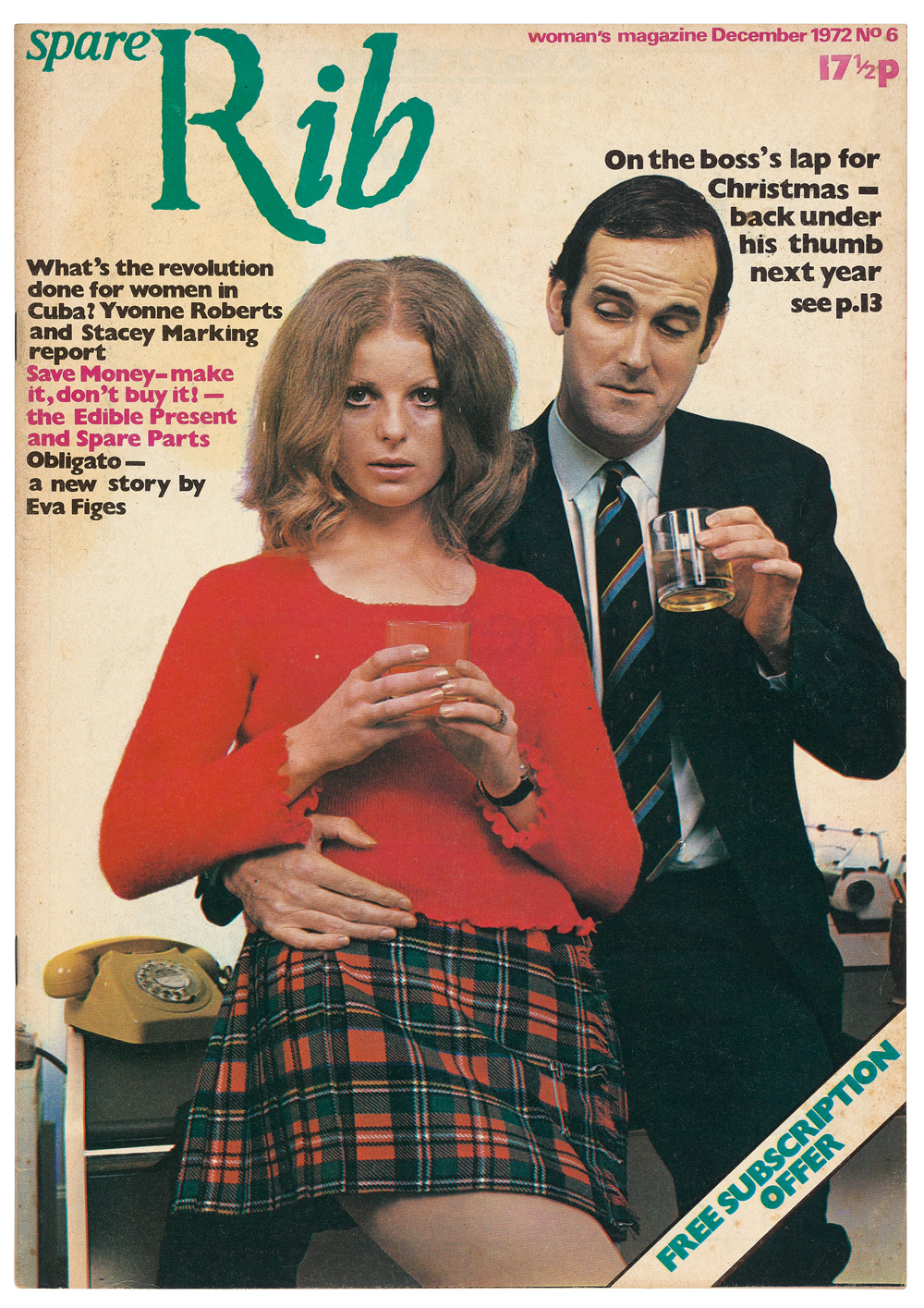

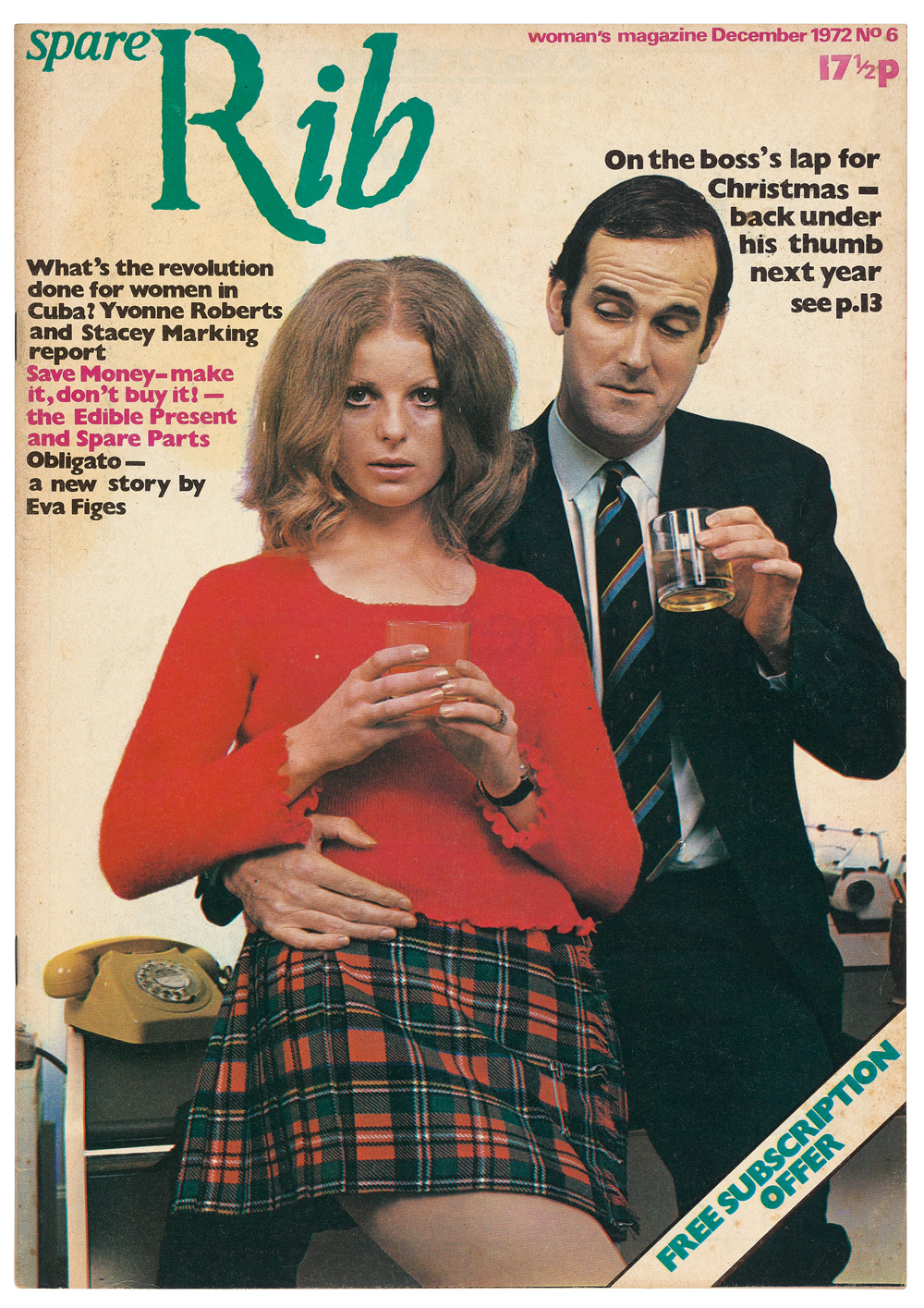

Top: Spare Rib no. 6, December 1972. Design: Kate Hepburn and Sally Doust. Cover photograph by Valerie Santagto. This satirical Christmas cover signals Anna Coote’s feature about ‘the female ghetto’ of secretarial work. Monty Python’s John Cleese is pictured with Marion Fudger, Spare Rib’s advertising representative.

The magazine went through several transformations during its lifespan: having grown from grassroots feminism, to later competing on newsstands. The editorial team adapted Spare Rib’s content and imagery to address myriad aspects of feminism, and dropped its editorial board in favour of a collective.

By November 1985, when Spare Rib was redesigned by Valerie Hawthorn (who was also working as Neville Brody’s design assistant at The Face), the magazine had become a vehicle for highly politicised agendas. Margaret Thatcher had been prime minister for five years, leaving the Labour party and its constituency side-lined and, according to members of Spare Rib, on the ‘back-foot’. Feminism itself had expanded into many more factions, including issues of race, religion and class, as well as queer discourse. Funding from the left-wing, Labour-led GLC (Greater London Council) came to an end in 1985 – the GLC was abolished in 1986. Organisations such as Spare Rib came under increased pressure to be more commercially viable. (Barbara Norden, designer and administrator at the time, remembers a tendency for alternative magazines to mimic the look of The Face.)

Founder Marsha Rowe said that by the end of the 1980s, ‘the revolutionary daring of Kate and Sally and their particular skills and genius at making the magazine look special were rather dropped.On the other hand, there were more and more women photographers and cartoonists coming along.’ A further change of look took place in October 1990. That issue’s editorial declared that the redesign had finally persuaded W. H. Smith to rack the magazine alongside other women’s mags, ‘where we feel we will reach the most women’ rather than in the ‘general interest’ section.

In December / January 1992, the Spare Rib collective published what turned out to be its final issue. Following its abrupt closure, Spare Rib’s Clerkenwell office was stripped of everything. Sue O’Sullivan, a member of Spare Rib’s staff from 1979-85, rescued a Women’s Liberation tapestry from the dumpster beneath the magazine’s first-floor office window. It was also filled with minutes, notebooks and readers’ letters that had formerly filled the office shelves and lined its walls.

Throughout Spare Rib’s twenty-year run, tensions within its collective made it a challenging environment to work in. Members recall political and personal conflicts, and arguments on an editorial and design level – where even a layout with justified text might be seen as ‘authoritarian’. Despite the difficulties faced by the magazine and its staff over the years, Spare Rib provided an accessible platform that promoted the sharing of ideas, knowledge and experiences. Doust says: ‘The team at Spare Rib had proved that the production of such a magazine could be entirely produced by women. We were a close team.’

In 2013, the British Library completed a digitisation of Spare Rib, available via their website and a good resource for research and inspiration.

Rowe says: ‘I was very pleased to see the way women’s magazines evolved and they started having inside them really everything Spare Rib would have had … Spare Rib broke new ground.’

Perhaps its greatest legacy was in letting women who shared similar views feel less isolated – the magazine was a physical artefact that connected women across the world – and the very act of publishing ideas and voices in print helped legitimise views and feelings that had previously been ignored or trivialised. The same spirit with which the Spare Rib collective drove forward their ambition to give voice to the issues of its time continues in publications set up and run by women today.

See ‘This woman’s work’, a profile of Kate Hepburn, also in Eye no. 97 vol. 25, 2018

Fi Churchman, writer, London

Originally published in Eye no. 97 vol. 25, 2018

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.