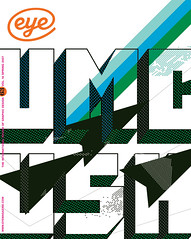

Spring 2007

Reason and rhymes

Kim Hiorthøy

Doyle Partners

Will Bankhead

Julian House

IWANT

Intro

Chris Bigg

Can design for contemporary jazz, world and experimental music have a meaningful partnership with the musical content?

Music design may not be the most lucrative area of design, but it often stirs the most passion. For many, it is the way they discovered graphics in the first place; their first teachers were Reid Miles (Blue Note), Vaughan Oliver (4AD) or The Designers Republic (Warp), say. Graphics can become inextricably linked with the music in a way that doesn’t happen elsewhere; powerful, iconic images that started on the drawing board or Mac of a music-obsessed, underpaid graphic designer will follow that musical content into the distant future, into formats unimaginable at the time of their creation.

Witness that heroically rendered advertising campaign for the iPod, which shows thousands of famous album covers, miniaturised and squeezed into the virtual space of Apple’s era-defining gadget. For pop, jazz and world music fans of the pre-download eras, a glimpse of the covers for, say, Milestones (Miles Davis), Revolver (Beatles), Soro (Salif Keita) or Walking Wounded (Everything But The Girl) will trigger an immediate audio memory. To use the terms coined by musicologist Nicholas Cook, the visuals either ‘conform’, ‘complement’ or ‘contest’ the sound in a memorable way. (See editorial, Eye no. 39 vol. 10.)

Is it possible, or even desirable for music design to represent – or settle upon some equivalence with – recorded music, the audio contents of a CD, LP or download file? In my other life as a music writer and compiler I receive about 80 CDs each month in the ‘creative’ (non-repertoire) genres: jazz, world music, electronic, experimental, contemporary classical, etc. This is an area in which designers expect to work with more freedom (if a lower budget) than in mass-market music packaging, yet they may also feel a greater responsibility towards the content. If this is music that expects a long-term relationship rather than a one-night stand, perhaps the artists and labels need to forge a bond with design that is equally deep, and which can be communicated to the listener. Fortunately there are a number of designers who are consistently successful in relating their work to musical content. And clients – both musicians and marketers – who value the relationship between sound and vision as a virtuous circle of culture and commerce. The pages following this article feature work by Kim Hiorthøy, Doyle Partners, Will Bankhead, Intro’s Julian House and Iwant, and labels such as Rune Grammofon, Nonesuch, Honest Jons, World Circuit and Buzzin’ Fly.

The single image

If we assume that music is more than a throwaway consumer item, its design works in three stages: the brief, the artefact for sale, and the rest of its life. The process is analogous to architecture in the sense that once the consumer has bought the product, he or she has to inhabit it, though for the record company, the packaging design is a means of selling an artefact. This is why designers are usually commissioned by marketing departments, rather than artists or creative staff. Kim Hiorthøy points out, only half-jokingly, that as soon as someone buys the album, the designer’s work is done (see page 24).

However for the buyer, the third stage is everything. Their experience of the music, their engagement and enjoyment will become wrapped up with the design and packaging and presentation of a particular album. Those graphics will spring to mind every time they listen to the music, whether following lyrics, reading the credits, opening the package or merely glimpsing the cover image in the iTunes browser. Yet as downloads become a more substantial part of the creative music market, the single image may become more significant than the details of ‘packaging’, changing the music-image relationship once more: the image chosen for Acoustic Ladyland’s Skinny Grin made its first appearance on the band’s MySpace site, predating the CD’s design (and for that matter, the album deal) by months.

The one-to-one relationship between music albums and single, memorable images is something that Apple exploits in the aforementioned iPod campaign. It is also echoed in the Beatles stamps (recently issued by the UK Royal Mail), whose tiny images rely upon our familiarity with famous Beatles albums. Notwithstanding exceptions such as The Catcher in the Rye and A Clockwork Orange, books, DVDs and classical music albums are routinely sent to market with visual makeovers. However few companies would dare repackage Bitches Brew or Man Machine. Even when older albums are re-released with new notes and elaborate extras, their front covers frequently pay elaborate respect to the originals. Look at Open’s design for the Smithsonian Folkways Anthology of American Folk Music (see Eye no. 53 vol. 14) and Doyle Partners’ ingenious anniversary re-packaging of Song X by jazz legend Ornette Coleman and guitarist Pat Metheny (see page 27).

Metheny’s albums have nearly always featured good design, from early ECM releases such as the hand lettering of 80/81 through Stefan Sagmeister’s famous ‘visual code’ cover for Imaginary Day, to Doyle Partners’ confident photographic system for The Way Up. Guitarist-composer Metheny may be the nearest thing that jazz has to a rock star – his CDs sell well, he has a loyal fan base and he sells out big venues for his long, demanding concerts. Nonesuch, his record label, is that now rare beast, a creative music label owned by one of the three remaining ‘majors’ – the Warner Music Group. Doyle Partners’ Nonesuch designs have an individual flair that nevertheless remains the servant of the music and fits well with their ‘editorial’ approach. Other designers who have made memorable and effective covers for the label include Hollis King, Evan Gaffney, Tracey Shiffman (Ry Cooder) and Edoardo Chavarin (Kronos). Barbara de Wilde (Bill Frisell, Viktor Krauss) and John Gall (Frederic Rzewski), are also known for their editorial design.

Brand benchmarks

Nonesuch’s designers typically make the most of the label’s larger budgets and manufacturing runs, with foil-blocking, substantial booklets and innovative use of ‘O-cards’ that cover (and soften) the plastic jewel cases. It is significant that Nonesuch CEO Bob Hurwitz worked for ECM’s US distributor early in his career. The label’s subtle approach to branding has been applied to other artists in the Warner group, such as Randy Newman and Wilco.

Many creative music companies adopt a consciously ‘branded’ approach, both to indicate a house aesthetic and to help sell to an audience for whom the label is much better known that any of the artists. Manfred Eicher’s Munich-based ECM is an example of this. Though its recent releases are thought to lack the grace and freedom of its earlier successes (see Eye no. 16) the label remains a benchmark for successful branding in the world of creative music. John Zorn’s uncompromising imprint Tzadik, Leo, Hat-Hut (see Eye no. 33), Emanem, Winter & Winter (see Eye no. 42) and the French companies Label Bleu and No-Format, are just a few of the outfits for whom modular design formats and simple branding are essential for economic survival. Paris-based Label Bleu has a more flexible approach, often featuring design by Jérôme Witz; Honest Jons and Soul Jazz Records, both founded by London record shops, are developing strong brands through the packaging of re-releases and compilations.

The company that comes closest to taking on ECM’s mantle is Rune Grammofon. Every sleeve on the label is designed by Kim Hiorthøy, clothed in digipaks with minimal typography and a vast range of illustrative approaches. The on-body designs are often impenetrable – flat colours and no type – but the musical contents are more diverse, ranging from the opaque noise of Supersilent to the glassy pop of Susanna and the Magical Orchestra.

Rune Grammofon is not far from ECM on the creative music family tree, since founder Rune Kristoffersen for many years had a day job at ECM’s Norwegian distributor. Another familial link comes from bassist Dave Holland, who left ECM to start his own label, which he licenses to Universal for certain releases. Holland’s latest album cover, by Niklaus Troxler, the Swiss designer celebrated for his jazz posters, might provoke a double-take from Holland’s earlier followers, a colourful graphic that represents the way the bassist’s music has been rejuvenated in recent years.

Chris Bigg’s design for David Sylvian’s album The Good Son vs. The Only Daughter (The Blemish Remixes) is a clever transformation of Atsushi Fukui’s delicate drawings for the cover of Sylvian’s earlier Blemish (2003). The elegant typography and distressed artwork are hardly unexpected, yet they cleverly hint at the content: sophisticated, exotic remixes of the raw originals. Looking at the muted ECM covers for poet and songwriter and former Incredible String Band member Robin Williamson, you might never think it the work of the bearded hippie whose The 5000 Spirits (or the Layers of the Onion) had one of the defining covers of the psychedelic era. In the later album, the ECM mood and house style prevails.

Sometimes, effective music design appears out of the blue, such as Karlssonwilker’s poetic cover for A Blessing (OmniTone) by the John Hollenbeck Large Ensemble, Art Spiegelman’s cartoon for The Microscopic Septet or Field Study’s haunting imagery for Stick Music by the Clogs.

Perhaps it is too easy to expect that a cover can genuinely represent the music within – and too heavy a burden to place on the designer or image-maker. Of the designers I spoke to, John Gilsenan and Bruce Allaway of Iwant, Stephen Doyle of Doyle Partners and Will Bankhead all placed emphasis on listening to the music, and entering the world of the musicians, whatever the genre. Yet there was also a rueful awareness that graphics can only do so much – that music continues to resist visual interpretation.

The documentary approach

The design of world music albums, whether approached as entertainment, art, ethnomusicology or ‘international’ (the industry’s original catch-all term) often benefits from a documentary approach to design and packaging, even when the artists are viewed as pop stars in their own countries. Maps, archive photos, detailed notes, credits and academic annotations supply raw materials for a design process that has much in common with editorial design. John Haxby’s designs for Topic take a respectful approach to the field recordings and research collected for previously neglected areas of music such as ‘gumboot guitar’ and Jarana’s Four Aces from Peru. Doyle Partners’ repackaging of the Nonesuch Explorer recordings has taken on heroic proportions as the collection approaches 99 releases over several years.

Will Bankhead’s designs for the Honest Jons compilations use archive photography and personal testimony to put the music in a time and place. Though the very diversity of such music collections might appear to resist simple music-image connections, Bankhead is quick to say how easy most have been to work on. Photography is used as a signifier for the contents, and the images are frequently chosen in collaboration with the label’s Mark Ainley, who compiles the CDs. Val Wilmer’s photographs in the digipak booklet for London is the Place for Me no. 4 are full of warmth and immediacy, while the anonymous cover picture creates an urgent, almost surreal context for this collection of African and Caribbean music from the capital. The most effective cover image is perhaps the second in the series, a striking portrait of a mixed race couple in Notting Hill Gate, by local photographer Charlie Phillips. ‘He just came in with his book,’ says Bankhead. Similarly, the Bruce Davidson photos that Bankhead uses for Son Cubano NYC and Boogaloo Pow Wow show not the musicians, but the people who would have listened to these rare dance tracks around the time of their release.

Collage and context

Cultural context is a starting point for Julian House’s CD designs (see page 29). While his pop / rock designs for Primal Scream and Stereolab are well known, his covers for World Circuit, London jazz label Dune, the experimental pop of Broadcast and his own Ghost Box releases bear closer examination. For House, collage is a fruitful way to make music design: it provides a way to express several, possibly conflicting cultural associations, and the process mirrors the way improvising musicians work. The documentary approach gets a distinctively House-like twist in his design for the groundbreaking Cachaito, by Orlando ‘Cachaito’ López, released under the umbrella of World Circuit’s multi-million-selling ‘Buena Vista Social Club’ series, but with an edgy, more uncategorisable sound. House’s choice and treatment of Christina Jaspars’ photographs from the album’s original recording sessions, together with the type treatment on the cover (and on the associated posters and marketing materials) evoke the feeling of a foreign-language cinema documentary yet to be released, and reinforce the album’s dream-like strangeness.

However much designers want to create design for music, the fear remains that album covers – perhaps albums themselves – may prove to be a historical blip, a short detour in the long history of music. The Rite of Spring didn’t need a sleeve design, nor did Duke Ellington’s East St Louis Toodle-Oo. With hindsight, the 78s of early jazz and folk music, with their ever-changing formats and anonymous paper bags (festooned with ads for hardware stores) are closer to today’s downloads than more recent music products. ‘Does the visual add something?’ muses Stephen Doyle down the line from New York, talking about the ‘incredible shrinking’ that has taken place during his career. ‘Maybe it’s the ultimate freeing up of music. Is the album cover the cord of the telephone?’ These are questions that the music industry – and music designers – may have to ask themselves as the industry realigns itself within the age of the download.

Good music is more than ‘product’; creative musicians are habitually less dependent on the fluctuations of the pop industry, looking to performance, teaching, multimedia and other forms of self-sufficiency in the face of an unsympathetic marketplace. If design’s old function as packaging declines, as music becomes disembodied entertainment software, perhaps the music design that survives will be in genres where the visuals forge a genuinely strong relationship with the sound, and where listeners expect imagery, content, information, style and depth in the way such music is presented to them. To use Doyle’s term, there is still a role for design that rhymes.

John L. Walters, Eye editor, Guardian and Unknown Public music writer, London

First published in Eye no. 63 vol. 16 2007

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.