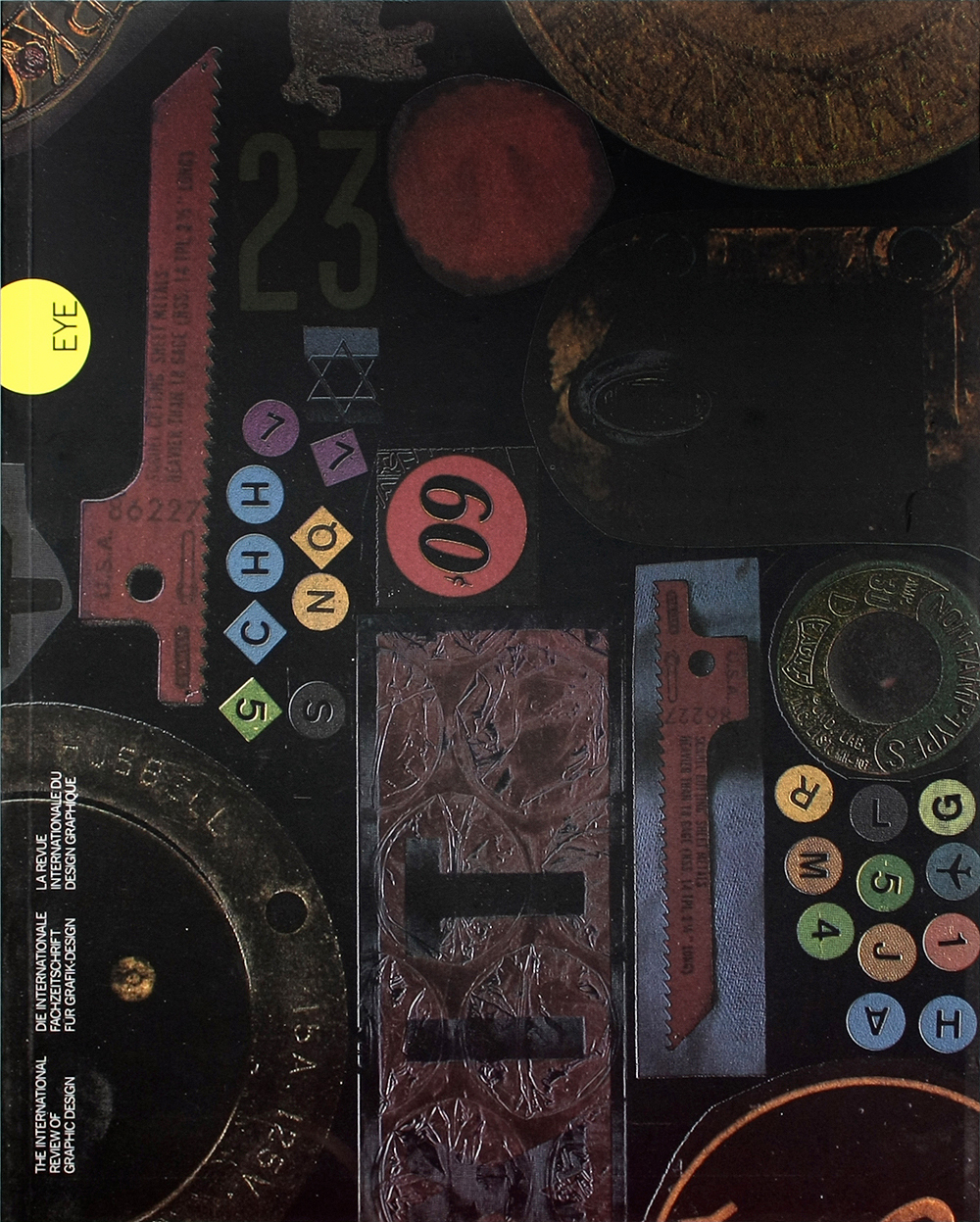

Winter 1990

Reputations: Alan Fletcher

An interview with Pentagram’s ringmaster of paradox.

Alan Fletcher was born in Nairobi, Kenya, in 1931. He studied graphic design in London before attending Yale University. After a year at Fortune magazine, he returned to London in 1959 to work as a freelance designer. In 1962, he co-founded Fletcher/Forbes/Gill and in 1972 he was one of the founder members of Pentagram, with Colin Forbes, Theo Crosby, Mervyn Kurlansky and Kenneth Grange. He was president of the Alliance Graphique Internationale [AGI] in 1983. In more than 30 years as a designer, Alan Fletcher has worked on projects for clients ranging from Pirelli to IBM. But it is in his many posters that Fletcher’s remarkable talent for ambiguity and paradox is most fully revealed.

Rick Poynor: Why did you become a graphic designer?

Alan Fletcher: I always used to draw as a kid and when it came time to leave school, you were offered three options. You went to university, or you went into the army, or you worked for the bank. I didn’t fancy any of those and I learnt that if you went to art school you could get a grant. I studied illustration at Hammersmith art school for a year, then I discovered there were other art schools in London. Central School was very lively so I applied to go there.

RP: Colin Forbes was at Central; so were Derek Birdsall, Ken Garland and Terence Conran. Did you have a sense of almost evangelical mission towards design? Were you as a generation going to bring design to Britain?

AF: It was an evangelical mission, not necessarily to bring design to Britain, but to do design. It was that 1950s period which was fairly socialist-minded – hair-shirt and puritan. There wasn’t much work around and you would have been mad to become a designer if you weren’t passionate about it.

From Central I went to the Royal College of Art, where I managed to get a scholarship to Yale. Britain was very grey, boring place and America, from what I could see in the movies, was bright lights, Manhattan, Cary Grant and Doris Day.

RP: You seem to have had trouble making contact with inspirational people there – with Paul Rand, Saul Bass, Leo Lionni. Was that something you set out to do, or was it just a series of happy accidents?

AF: It was a bit of both. If you know the right people, you meet the right people. I happen to have been taught by pretty terrific people at most of the schools I went to – Anthony Froshaug, Henrion, Herbert Spencer, Herbert Matter, Josef Albers, Bradbury Thompson. When I was at Yale, Rand helped me by giving me the odd freelance from IBM and introduced me to other people. But you have to work at it. When I went to Los Angeles, I called Saul Bass from a public phone box and said “Sorry to bother you, sir. Can I come and see you and show you my portfolio?” I didn’t have any money, so he helped me by giving me freelance work.

RP: It seems as though you knew exactly where you wanted to go.

AF: Well, I think it’s the reverse. I couldn’t actually do anything else. I always thought I could design well as a student, but then I would find someone who could do it better. But it wasn’t so far off, it wasn’t unattainable, it was just difficult. So I was driven by my own inadequacy, probably. You’ve got to have an ego to be a designer. It’s a stupid job to have unless you’ve got that: undressing every day in front of some client who doesn’t necessarily share your enthusiasms.

RP: The American experience must have given you a headstart over people who had stayed in austerity in Britain.

AF: Everybody was still doing the same thing: little black and white jobs with eight point type. If it had a second colour it was red, or possibly blue. When I arrived back in London in the early 1960s it was with a portfolio of full colour jobs and ambitious hopes.

I had been back about six months when Bob Gill rang, saying he had been given my name by Aaron Burns in New York. We went out for supper and after about three months we decided we should start our own little design office with Colin Forbes. We didn’t get a single job for the first month. Then we got some Penguin book jackets. We used to go out to a café with the brief for one Penguin book jacket and do it over coffee, share the book jacket like a bone.

RP: At Pentagram you have the controlling influence on everything you do. The assistant designers support your vision. Do you think the best graphic design will always come from a single author?

AF: I think it depends on your personality. Art directors orchestrate other people to produce something that satisfies them. That’s OK. And then there are other people sawing away on their violin. I’m up the violin end. A John McConnell likes an orchestra and he does it very well. I couldn’t do that: it would be totally confusion after about three minutes. But in the end the result is the same.

RP: With Pentagram you co-operated in the setting of a partnership that would give you the freedom to pursue your own interests and a secure company framework within which to do it.

AF: I’m a split personality. I do quite large, complex corporate identity jobs. I enjoy that, but I also enjoy sitting round doing my own little things, which are invariably the ones that don’t pay. The clients who do pay give you an opportunity to extract time and money for your own indulgences. That’s important. I think a lot of clients come to Pentagram because of the uncommercial jobs we do – calendars, Christmas books, the Pentagram Papers and so on.

RP: What else have you gained from the Pentagram arrangements?

AF: You can’t get away with anything in here, because someone is going to pass by something on your desk and say exactly what he thinks. You have to listen to it, because you respect his opinion. You don’t necessarily agree, but you are uncapable to kid yourself that the job is good if it’s only 80 per cent. But it’s very easy, if you’re tired and you can’t think of anything else, to convince yourself that you’ve solved it. So the partnership acts as an irritating self-protection system.

RP: You once told me that up until five years ago you felt inhibited in your designing. You knew in advance what you would or wouldn’t like and this influenced the solutions you were prepared to attempt.

AF: What I meant was that you have to throw away the crutches. When you know that you do a certain thing quite well there’s a temptation to keep doing it in that way. You become a graphic cliché.

Most designers suffer from inhibition and wanting to please. I didn’t wake up one morning and say “I’ve got to change my life”. I just thought: I’ve got to be less inhibited. If I think the right answer is to walk over a piece of paper with muddy shoes, or pick a typeface that everybody loathes but try to do something with it – that’s what I mean by uninhibited. I think a lot of designers talk like that, but the work ends up looking the same, which means they haven’t totally let go. I haven’t either.

RP: Design as you practise it seems to involve reading between the lines. When you use visual puns and rebuses, or pay with ambiguous images, that’s what you are encouraging the viewer to do.

AF: That, to me, is what design is. The rest of it is just layout. I’m quite broad about ideas: putting certain colours together could be an idea, or an optical idea. Every job has to have an idea. Otherwise it would be like a novelist trying to write a book about something without really saying anything.

I also like ideas that have further jokes – private ideas or jokes. I think the Polaroid poster is quite a good one. We were asked to do something on a new colour film and I thought that idea of a Rorschach test with colours would look quite pretty. What I really liked about it, though, was when someone said to me, “But what does it mean, Alan?” I just shrugged my shoulders and smiled.

RP: You don’t mind if there are aspects of design that people fail to grasp?

AF: It’s the extra three or five per cent, if you like. You’ve solved the problem – that’s difficult enough – but it’s not enough. I think what separates the designer sheep from the designer goats is to push it to the edge. Most clients don’t realise it and couldn’t care less even if they did, but it people who have a sensitive intelligence spot it, then that’s what gives it extra buzz.

RP: That’s a view of design that would be foreign to people who regard it as an adjunct to marketing – people who see design’s function as fulfilling the client’s brief as effectively as possible and stopping there.

AF: I treat clients as raw material to do what I want to do, though I would never tell them that. I try to solve their problems, but in solving their problems take an opportunity to find that extra twist that adds the magic. The art posters I did for IBM are a good example. IBM asked me to design a placard for their new Paris headquarters, which said a painting would shortly arrive for the space on the wall occupied by the placard. In response I did a series of posters interpreting the word “art” as defined by author or artist, and I put the line about the paintings in 6pt along the bottom. If I had answered the brief, they would have got a straightforward placard.

RP: Why do you use your own handwriting so much in the posters?

AF: I like to reduce everything to its absolute essence, because that is a way to avoid getting trapped in a style. I only started writing instead of typesetting to save money, or maybe because I was inhibited before. You’ve got to keep on breaking down the barriers. Of course you could argue that I’m creating my own style and that’s a weakness and I should try harder. I think you would probably be right.

I always think of writing as drawing. Every letter is a symbol, so you can begin to play games. I don’t treat writing as calligraphy. The more controlled and raw it is, the more interesting it becomes

RP: What qualities of thought or sensibility make for a good graphic designer?

AF: There are elegant ways of doing something and inelegant ways. Sensitivity, though it sounds a bit fey. Thoughtfulness, I think you can look at a portfolio and see the obvious things: if they have idea or don’t have ideas, a sense of craft. Then there’s that quality … You hardly ever see it. You look at other designers’ work and you spot it, and they spot it, too: economy of thought, the oblique reference, charm and, above all, wit.

RP: Do you feel that the approach you and the other Pentagram partners have taken – avoiding the stock market, creaking an environment where you please yourselves rather than shareholders – has been vindicated by the recent upheavals in the British design business?

AF: It’s not a question of vindication. I think everyone should do what they want to do. Every Pentagram partner in his own way is a hands-on person. They are all small boys who want to be patted on the head and told what a nice job they’ve done. What turns people on here is being proud of the job, not how much money they earned for it. I can’t see a suit coming in from the City and saying, “Look, you can’t do this. You’ve got to do that.” They’d throw him out of the window.

RP: You’ve been working on a book about design for seven years. When will you publish it?

AF: It’s really a scrapbook. I wrote down some thoughts on a whole series of things like “taste”, “perception”, “imagination”, “visualisation” – pigeon-holes. I took all the quotes, clippings, observations and images I’d collected, including my notes, and put them in the pigeon-holes. There are lots of things written about the visual business that are not explained very clearly. I’m using words like pictures.

The rest of my life has lots of deadlines, so I’ve no intention of that happening to something I’m doing for myself. I’d like to see it published, because I think that would be an achievement, but if it isn’t, it isn’t going to kill me. I’m trying to learn something more about myself, actually. I’m not given to self-analysis, but I am given to insatiable curiosity

First published in Eye no. 2 vol. 1, 1991

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.