Autumn 1993

Reputations: Alexander Liberman

‘I think the term “art director” is the greatest misnomer. There’s no art in magazines unless you are reproducing works of art.’

Alexander Liberman was born in Kiev, Russia in 1912. He studied architecture at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Paris, in 1930 and worked briefly for the poster artist A. M. Cassandre. From 1931 to 1936 he was chief layout artist, then art director and managing editor of Vu magazine, where he collaborated with photographers such as Brassaï, André Kertész and Robert Capa. In 1941, fleeing the war in Europe, Liberman arrived in the US. At Condé Nast he was hired as an assistant to Vogue art director Mehemed Fehmy Agha and in 1943 succeeded him as art director. During his tenure, Vogue was transformed from a sedate society album into a more journalistic title; it was, for instance, the first to publish photographer Lee Miller’s pictures of the Buchenwald gas chambers. Liberman brought fine art to Vogue’s pages – sometimes using painting as a backdrop to a fashion shoot – created a series of photo essays on artists in their studios, and developed an intense working relationship with photographer Irving Penn. Since 1962, when he ceased to be art director, Liberman has been editorial director of Condé Nast, with responsibility for such titles as Vogue, Mademoiselle, Glamour, House & Garden, Traveler, Details, Allure and Vanity Fair. He has mounted several exhibitions of his paintings and sculpture. His book The Artist in his Studio, first published in 1960, was revised in 1988.

Susan Morris: In the flat in Moscow near the Nevsky Prospekt that you lived in when you were a child, you had a white room. I wonder if that had any impact on your aesthetic development – that you’ve remembered it as being your first contact with white?

Alexander Liberman: Possibly. And my late wife Tatiana, who was Russian, also loved white. All her houses and apartments were white. She loved white and I loved white and frankly even in my painting and even in some sculptures, I love white. I love the two extremes of red or white. To live with, certainly white. I’ve just bought an apartment in Florida with my new wife, and it’s going to be white. White for me is the primary colour.

SM: You’ve also said that you had your first experience with photography when your father bought a Kodak pocket camera. Did that make you see the world differently, make you frame it in a particular way?

AL: I’m not sure about that. My father was always an amateur photographer, he always had cameras. Later, when I was in school in England, I started to play with photography. Then later at Vu I worked with photographs, made layouts and did a lot of photomontage, which meant projecting different pictures. I’ve always worked with photographs, but I never, never, never considered it design. Maybe I just didn’t put the right name to it - it was layout, or a cover, but ‘design’ meant composition. Maybe it was instinctive composition, I don’t know. But I thought I was fitting things into a journalistic pattern and solution and I didn’t pay any attention to space, or white space. It’s like The Bourgeois Gentilhomme - the man speaks prose and he says ‘I didn’t know I was speaking prose.’

Conscious design in a way means self-admiration. It means appreciating spaces and lines and stepping back and saying, this is handsome. I never worried about things being handsome; I wanted things to be catchy, or expressive, or to tell a story, and many of the things I put down on paper I probably wouldn’t even call layout. It was just a means sometimes awkward, or transmitting or translating an emotion that I thought would complement the journalistic interest.

SM: You’ve described yourself as a pictorial journalist. So what’s the balance for you between word and image? Do you think in pictures or in stories?

AL: It all depends on what you’re dealing with. But for me it’s the thought that always comes first. What is it about? What am I doing? What is this for? In one’s mind, word’s come first.

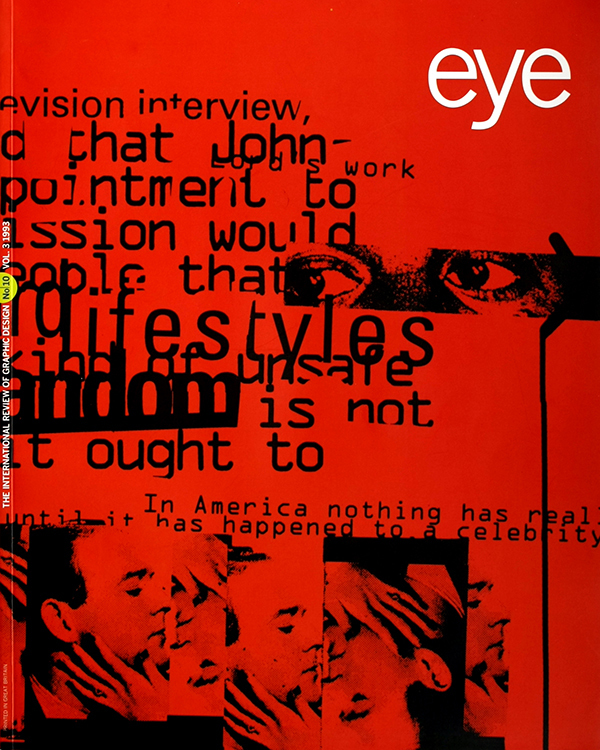

In certain instances, of course, you put down pictures that perhaps look better next to one another. But I don’t design, that’s not design. What I call design is this cover [gestures to a copy of Eye no. 5 vol. 2] – especially that square where somebody put a triangle in the pinpoint of this, and this is lined up with that. Well, why not? But basically, it’s everything I dislike about what is called graphic art.

SM: What did you learn from your time with Cassandre?

AL: That’s a lovely decoration I carry with me, but in fact I spent only about three months there, so it wasn’t much. I did learn, or saw, how Cassandre posters were made, but it was a process that was very special to him, and there were many other poster artists who worked differently.

I did learn more from Cassandre about typography. He had a great gift for lettering, and I think my interest in lettering may go back to the period when I was with him. His great friend, and [founder of Vu] Lucien Vogel’s friend, was Charles Peignot, who had the great Deberny & Peignot typographic business, so the catalogues were masterpieces, and they are still very rare and hard to find. When I came to America I wanted to use certain letters, like beautiful Didot, that did not exist here, until photolettering came into existence and they copied that letter for Vogue – I think Vogue had an exclusive … we had a design similar to Didot type, which they re-photographed.

SM: What was the attraction of magazines?

AL: First of all, it was a way to earn a living. It started with that – I had to earn a living. It was a job. I was doing several jobs then: window displays, advising on several magazines and newspapers, and this seemed a natural step. Here was a man who said, I want you in my art department if you worked with Cassandre. So I said, well, he wants me, I’d like to try.

SM: One of the things that has been consistent throughout your work is the influence of fine art – the fact that you make fine art as well as being an art lover. What was the influence of fine art on your approach to magazines?

AL: I always thought fine art was the central core of my life. And I always considered jobs – working on magazines – a second-class operation that earned me a living. It’s perhaps very rude to say what I’m going to say, but one of the secrets of good magazine work is contempt. You must not fall in love with something which shouldn’t occupy the centre of your life. Magazine work – call it design or whatever you like – was never the centre of my life, so it was easily dismissed and perhaps that was one of my strengths. It was quick, I could dismiss it quickly, and frankly I don’t think it had any connection with fine art, except that of separating what was truly serious from what was less serious.

I don’t consider any magazine work as really serious. As somebody once said to me, ‘Alex, after all, all this is entertainment.’ I have more illusions than that, but it opened my eyes to what people really consider you are producing. You are producing something that’s supposed to interest, amuse, entertain. Now I suppose if I were designing a new Bible, if such a thing is possible, I would treat it with a certain respect. But I cannot say that the sort of subject matter I have been involved in, except at Vu, merited any great respect. Nice fashion pictures and pretty girls – and I like pretty girls very much, so it always entertained and amused me.

SM: Is art serious?

AL: Art is sacred. Good art should be. And I have always believed and attempted to fulfil that dream. It’s very hard, very difficult – maybe one is distracted, and then it’s hard having a job, having to stop painting, to drop everything even in the middle of a work to go to where you earn your living. I think the term ‘art director’ is the greatest misnomer that ever existed. There’s no art in magazines unless you are reproducing works of art. Otherwise, to consider any spread or cover as art … we don’t know what we are talking about. It’s as bad as saying that photography is art.

SM: Given that, what were you trying to do with your magazine work at Vu?

AL: I was trying to fulfil a function and do a job. It was a question of getting the things on paper, and getting them out. You have to squeeze things in, squeeze them out; it was much more a business of packing suitcases and sending them off. Thank God they went off quickly. The only small reward was to encourage, develop, and present in importance work that you perhaps felt had quality. That was the great satisfaction for me at Condé Nast, to help develop talent, encourage talent, by whatever means I had. And then progressively, from two magazines we became 14 magazines, and I felt much better being an editorial director than being an art director.

SM: Why is that?

AL: I didn’t have to be involved with all the boredom of corrections and counting lines, all that tedium that today is becoming simplified thanks to computers. But in those days, let’s say at Vu, there were no photostats, no Xeroxes. You had to use a slide rule. If you wanted a silhouette, you had to draw it – you looked through a special little glass, and you had to go and project it – it was so primitive. In reality, I did very few layouts at Vu; it was Irene Lidova who did practically all the layouts, or an assistant she would hire. But I would receive the photographic agencies, I would talk to photographers, I would give out assignments, and do the covers, most of the covers.

SM: When you arrived in the United States, did you go directly to Vogue?

AL: Yes. I went to see Brodovitch first at Harper’s Bazaar, but he didn’t have anything for me. Lidova was a pupil of Brodovitch, and she gave me a letter of introduction. But what I’ve discovered recently is that when Irving Penn, the art director of Saks, offered me the job of replacing him because he wanted to go off and paint, it was Brodovitch who recommended me. He said: ‘There’s a young foreigner there who has talent.’ I didn’t take it – and later I hired Penn as my assistant.

SM: What were your ambitions in working on a fashion magazine like Vogue rather than on a general interest magazine like Vu? What were you trying to achieve?

AL: In his later years Condé Nast was hoping to make Vogue much more journalistic, more understandable, and I think he liked the idea of my coming from a news magazine. He liked the idea of putting captions under documents, having titles on top of the page. What I tried to do – what I felt to be my raison d’être – was to modernise Vogue from a sort of slow women’s album to something closer to news. The typography changed, the photography changed, and I tried to introduce the same approach to fashion photography that had interested me with news photography. I liked to use news photographers and I tried to send more photographers into the street; some, not all, because you need variety. I think the really big chance I was given, as I said before, was to help to develop and encourage talent and to modernise the magazine. I was trying to eradicate what I used to call Park Avenue taste. From elegant typography, I went to rougher typography. Women were, forgive the word, growing up; they were intelligent and interesting human beings, yet they were being treated like little dolls and ninnies. I like women too much, I adored my wife, and I thought that women should be treated as interestingly as any subject presented to men. So instead of phoney low-level Marie Laurencin art, we published Picasso or Braque. We were the first to publish Pollock and Abstract Expressionism. I fought to introduce real art, if art was to be published; I think it was important to expose women and Vogue readers to what was serious and real and noble in what was happening around them. Vogue at that time was still led by Mrs Chase and her mauve pearls – it was time for a change and I think I helped to accomplish it. There were editors who were wonderful – Eileen Tauby, Jessica Davies – all these women had intellectual interests.

SM: When the Condé Nast titles began to grow in number, were you trying to implement some kind of wider vision?

AL: I think both Si Newhouse and I wanted quality, we wanted the best of everything, and my job was to help supervise each magazine. I don’t think there was a single formula – on the contrary, I resisted that. Allure and Details are very different from Vogue or from anything else. And I know there’s a legend of a Condé Nast style, but I think the Condé Nast style is just journalistic involvement with what’s exciting and good.

SM: You don’t think it’s also a kind of look?

AL: I honestly don’t think so. Because, look, I don’t do those pages. They’re shown to me but I don’t say, no, make them alike. Perhaps there’s a continuing spirit of vitality. What Si and I like to look for is a sort of adventurous excitement and dynamics on the printed page. There are magazines I have nothing to do with; I don’t do a thing with Glamour, I don’t do a thing with GQ. I see Glamour covers, but I don’t touch a page; I don’t touch Gourmet either. There are many magazines – I concentrate on those areas I think need attention.

SM: What exactly does it mean to be editorial director?

AL: It means finding strong editors. You see I’m more interested in content than in detail. It may mean an overall evaluation, or deciding the direction of a magazine and its effect in relation to other publications. We discuss that a great deal. Is there too much of this or that? We may call in the editor: do you think it would be more interesting to add this or that? But the fact that a certain article goes in – that’s the decision of the editor.

SM: Was this a position that grew up around you?

AL: Possibly, because Condé Nast was in the hands of people who were involved with the financial side, so there was nobody to control or look at the editorial side. They trusted me to combine my visual sense and my journalistic sense to supervise and guide. And I’d be called in: one editor wants 16 pages for this, another editor wants 10 pages for that; someone has to help decide. So I would be used as an adviser more than a director. And if behind the scenes I gained a certain authority, I don’t think I ever exercised it.

SM: Can you give me a thumbnail sketch of your typical day?

AL: I don’t know. People come and talk to me, show me things. Or Traveler calls, I go over to Traveler, and they show me a series of layouts. And sometimes I say, what about dropping this, or making this bigger. Or I say, what is the cover? Maybe we should change it. Maybe the type is too heavy. I always say maybe to ask their opinion – what do they think?

SM: I’ve read stories about you being somewhat more dictatorial.

AL: Possibly.

SM: Can I read you a quote [from Eye no. 5 vol. 2]? Barbara Kruger describes her time at Condé Nast: ‘We had to do 12 layouts for each spread. We couldn’t paste anything down; we had to fold it. Everything was provisional, so that he could walk in like the Prince of Wales and see 12,000 layouts with very slight increments of difference.’

AL: Where was she? On what magazine?

SM: She was on Mademoiselle, and then she freelanced around. How do you react to that? Are you the fearsome dictator?

AL: If I am, I don’t know it. I had no idea they made 10,000 layouts. I think there were art directors who wanted to show me a great deal, but I don’t know. I’ve never seen 10,000 layouts. There’s no such thing. In the beginning, maybe at Glamour, we did struggle a lot because it was beginning to gain strength. It had to find its raison d’être and I didn’t know what that should be. We all struggled with it. There were many attempts at this or that: is this better? Six pages or four pages? But if the editors or art directors really awaited my arrival, I think that’s a sign of their weakness. Because there are magazines where things are ready and done, and usually it’s very good. I don’t demand quantity at all. I myself have a tendency sometimes to make 20 variations, because everything is possible and there’s no absolute thing that’s right. To choose a thing that is right you have to know what precedes it, what follows it, how many pages, then you have to condense it, then you have to change it again. But the only thing I was always interested in was flexibility to the last minute.

SM: One of the things that interested me last time we spoke was what you said about the new technologies and a different kind of sensibility that you find attractive. Things like faxes and colour Xeroxes and computer graphics – you could call it the MTV sensibility. Why do you find this so exciting?

AL: Television is very exciting, and I think magazines have always followed the exciting medium of the moment. Once it was films, now it’s television, and I think the great revolution that’s happening, of which I really know very little, is the use of computers. I go into a room and there’s an idle pattern going on on screen, and it’s marvellous. Of course, outdated colour printing is changing too. Our demand for more exciting colour is dictated by our eye constantly seeing electronic colours. And Mr Newhouse and I are coming in and saying: what is he doing with this photograph, because it looks much more intense? Well, the art director is working with the engraver and they are changing colours, and things are happening. I was told yesterday there’s an extraordinary four-storey press that can print a million things in 24 hours, with perfect register, and extraordinary colour. All of this is happening around us. I haven’t seen much of it, it’s not for me to see. But what is happening I find wonderful – it’s something I have dreamed of for a long time.

SM: Does it make you want to get your hands on the technology?

AL: I’m too busy with my own art. I have no hankering to adjust. I can’t stand that.

SM: If you were just started now, what do you think you might be doing?

AL: I think the same thing. I’d love to paint: sculpture or painting. Possibly I would go into photography. I enjoy photographing artists, but I would hate to be a fashion photographer. Perhaps I would even like to be a museum photographer, or to photograph the great miracles of beauty in the world. There’s a book coming out on the Campidoglio in Rome that I’ve been working on for over 20 years. Every time I went to Rome I photographed different moments. That’s really something that can be deep: honouring and admiring the eternal qualities of art.

SM: You have said that circulation didn’t always have such a stranglehold on magazines. Is that a damning indictment of today’s market-led approach?

AL: Yes, it is. Here you are talking about magazine practice as an art form, when in fact they are now sold in supermarkets and have to compete with the vegetables or the Enquirer. The thrust all the time is to lower standards. That’s why I feel magazines will continue to exist, but forget any creativity. I mean, anyone who breaks his heart laying out with design passion a story on home cooking or whatever is just a moron.

SM: What advice would you give to young designers working in magazines today?

AL: I would say, look, do a wonderful job, be the best layout man, but if you really have a deep creative urge, so something else on the side. Maybe that’s my example, but I think it’s cleaner than having ulcers and destroying oneself, because in the long run magazines are very destructive of creativity.

SM: Have you seen a lot of casualties?

AL: I’ve seen a lot of people suffer a great deal. They suffer if a layout is changed. They suffer because they put so much into something and then somebody comes in and says, no, I don’t like it, and they feel something of theirs has been hurt. Don’t be hurt. This is work and there are certain necessities. Pages are reduced, or increased, or changed, and that comes from decisions that are financial. Don’t be hurt by that. Be satisfied with another life. It’s not an easy medium and it shouldn’t be if it’s any good.

Susan Morris, television producer, The Late Show, London

First published in Eye no. 10 vol. 3 1993

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.