Autumn 1994

Reputations: Dan Friedman

‘Radical modernism is my reaffirmation of the idealistic roots of our modernity, adjusted to include more of our diverse cultures’

Dan Friedman was born in Cleveland, Ohio in 1945. He received his education at Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, the Hochscule für Gestaltung in Ulm and the Allgemeine Gewerbeschule in Basel. In the early 1970s, at Yale University, he developed and published teaching methods in design and the ‘New Typography’ which became a basis for the New Wave which followed. He also developed guidelines for the first programme in visual arts at the State University of New York in Purchase. As a graphic designer, he has created posters, publications, packaging and visual identities for many corporations and organisations. In the mid-1970s he was senior design director of Anspach Grossman Portugal and in the late 1970s he joined Pentagram, became an associate and helped to establish the New York office. In 1982, he returned to his own private practice and in 1991 returned to teaching as a senior critic in graphic design at Yale University. Although he retains an interest in education and graphic design, his art, installations, furniture and ‘Modern Living’ projects have generated exhibitions and commissions all over the world. His first solo exhibition was at the Fun Gallery, New York in 1984. His experimental furniture has been produced by Neotu in Paris and by Arredaesse, Driade and Alchimia in Milan. His work is in many public and private collections, including the Museum of modern Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Gewerbemuseum in Basel and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Montreal. He describes himself as an artist whose subjects is design and culture. Dan Friedman died on 6th July 1995 (see editorial, Eye 18).

Peter Rea: Could we begin by talking about how you see the graphic design profession today?

Dan Friedman: For more than 25 years I’ve had love-hate relationship with our profession. I will defend it with pride and passion, but I will also be critical – even occasionally cynical. I’ve been at its centre, but I feel more comfortable playing at its margins. It is a profession which involves a great deal of drudgery and concern about minutiae that can only be measured in quarter points and millimetres. Graphic design has always defined its focus in narrow terms – in ways that may stimulate graphic designers into a frenzy but mean nothing to the rest of society. When we try to extend our reach, as with fantasies about the emerging potential of multimedia, our ideas pale in comparison with Terminator 2, a U2 concert of the latest Las Vegas hotel. I believe it is a profession in an identity crisis caused by over-specialisation and deep polarisation.

PR: How did your sense of disillusionment begin?

DF: My disaffection reached a peak in 1982 when I chose to step off a fast track as an associate of Pentagram New York and exhibit my art with graffiti artists in a gallery called ‘Fun’ on New York’s Lower East Side. I found work in commercial design too predictable and not sufficiently sustaining. In the 1960s I saw graphic design as a noble endeavour, integral to larger planning, architectural and social issues. What I realised in the 1970s, when I was doing a major corporate identity projects, is that design had become a preoccupation with what things look like rather than with what they mean. What designers were doing was creating visual identities for other people – not unlike the work of fashion stylists, political image consultants or plastic surgeons. We had become experts who suggest how other people can project a visual impression that reflects who they think they are. And we have deceived ourselves into thinking that the modernisation service we supply has the same integrity as service to the public good. Modernism forfeited its claim to a moral authority when designers sold it away as corporate style.

PR: Where did your interest in design start?

DF: When I was 12 years old, in the 1950s, my parents moved to the suburbs of Cleveland, Ohio. They had found some success and had the money to build their own suburban dream home, which was the same dream home of almost everyone else in America. So as a kid I was exposed to the process of watching this dream home taking shape. My parents, particularly my mother, were actively involved in the decisions about how the house would be laid out, the colours and the decor. I was fascinated by this process, the first inclinations I remember of being interested in design of any sort. In dreaming and playing I became fascinated with architecture and would do drawings of fantasy houses, cars, all very futuristic, like the Jetsons. Along with their robotic maid and dog, the Jetson family had the most wild futuristic furniture and decor which to this day seems very modern. My next book which I am currently working on, is about the aesthetics of suburbia.

PR: You studied graphic design in the United States, Germany and Switzerland. What did you get out of this international education?

DF: At the age of 18, in 1963, I went to school at Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh – what is now Carnegie-Mellon University. It was one of the two schools in the country where printers sent their sons (maybe even their daughters, although at that time that’s doubtful). Carnegie-Mellon had a good fine arts programme, one of the best drama schools in the country and a graphic design department. I was interested in theatre, but I realised I had no talent for it. So I followed my instinct, which was to create printed things.

You have to bear in mind that though there was an activity at the school called graphic design, it was essentially commercial art. Most of the dominant practitioners and teachers considered themselves to be commercial artists. The term ‘graphic design’ was relatively new and predominantly European-influenced. In Switzerland and Germany there was a sense that graphic design involved a more rational methodology, not just craft.

PR: Was it this interest in methodology that led you to study at Ulm in Germany?

DF: While I was a student at Carnegie people from Europe would occasionally show up to give a lecture, including people from Ulm. Then, in my second-to-last year, Ken Hiebert arrived to teach. Here was someone who was totally off-the-wall compared with the dominant influences in commercial art, advertising layout and calligraphy. This was Hiebert’s first teaching position after his studies at Basel – later he moved to Philadelphia College of Art, where he has been for at least 25 years. He was one of the first wave of people returning to America after having studied at Basel under Armin Hofmann and others.

So having been exposed to European influences in design, I realised that, generally speaking, education in design in America is unsophisticated. I saw Europe as a Mecca for study in advanced design. Then in my last year at college, I saw a notice for a Fulbright scholarship to Germany. The journey was an emotional experience: to come to New York from Ohio, from deep in the country, to be placed on a boat by my parents, waving goodbye, like you see in the movies, with streamers falling. I was leaving a country where I couldn’t find satisfactory design education. I was leaving a country in social upheaval. And I was leaving in a sense the connection to my childhood and my family. It was a major cultural transformation.

Ulm turned out to be nothing like I’d expected. It had evolved from when it was founded in the 1950s, when Max Bill was there, into a place which saw design as a science. This was not necessarily my own inclination, but I got caught up in studying other disciplines such as information theory and semiotics to learn concepts which could be transposed to communication design. The course structure alternated weeks of studio courses with purely theoretical lecture courses is psychology, communication theory, mathematics, which is where I learned most of my German. Ulm’s strength was probably in industrial design – I thought visual communications was quite weak. And I had my mind set on going to Basel.

PR: What differences did you find between studying Ulm and Basel?

DF: I’m thankful for Ulm’s theoretical approach – Basel was much more art-based and intuitive. People often believe these two places represent the same thing, but nothing could be further from the truth. People see the similarities in style and don’t look any further. The work at both places is seen by some as pure and minimal, maybe a little Germanic, black and white.

PR: I always believed Ulm to be a place where people thought as though in a monastery.

DF: In a way Basel was as much like a monastery as Ulm, thought Ulm was literally situated like a monastery in the woods. In Basel one probably contemplated more than at Ulm, where people were talking rather than contemplating. The other factor at Ulm was that in the end it was highly political Radical students would go to Nazi rallies and disrupt them with smoke bombs. At a certain point the school was disintegrating before my eyes. I realised that my heart was in Basel and perhaps my brain was in Ulm.

PR: Who were your teachers at Basel?

DF: They initiated a postgraduate class the year I arrived and I was the first of only a few Americans enrolled in it. The influential people who taught me were Armin Hofmann and, less well known, Kurt Hauert. Hauert’s courses were almost all about drawing. Students would spend a whole semester, half a year, drawing a cube or a leaf. And when you had demonstrated a ‘Zen’ mastery of this, you could, maybe move on to something as complex as a bottle. In other classes you might have drawn straight lines. Hauert was softly spoken, generous and ego-less. He was very important to me and often my preferred teacher. Wolfgang Weingart had just started teaching too, taking over for Ruder, and we were more like peers and friends, learning together. We shared a fascination with and reaction against more rational, Modernist approaches such as those taught by Bill, Müller-Brockman and Ruder.

What few people have realised about Hofmann is that behind the artistic beauty of his design was a strong conviction about cultural, moral and social issues. Out of the turmoil of the 1960s, I saw in his work an alternative approach to that of hippie culture. Modernism now seemed too constrained, too orthodox, too exclusive. At Basel we tried to work against the grid, not with it. In our 1960s idealism we still thought industry had integrity and potential. At the time it was assumed that we were part of an industrial society which contributed to improving modern life. Advertising was the area in which you had to work with caution, not industrial corporations. There wasn’t a perceived separation between the values that were important to society and the values that were important to industry. In time, I came to be disillusioned with that idea, but at the beginning on 1970 I came back to America from Basel even more determined. And because I’d been so disappointed by the quality of education I’d received in America, I came back dedicated to being a teacher. Hofmann was my principal mentor in this and he more or less pushed me into teaching at Yale, where he had been a visiting professor. So there I was at the age of 25, a professor at Yale.

PR: So what were the principles against which you were struggling?

DF: It mainly had to do with being reductive – reducing messages in their essentials, relieving the typographic composition of extraneous information, producing a communication which purports to be universal. Simplicity, precision and purity of form were the goals, and while I found that agenda important, it was also limiting. So we experimented with ways of working against those limitations by including more information, different levels of information. One of my problems was that the orthodoxy we were working against in Basel was generally unknown in America – so how could I teach people to work against something they didn’t even know about? There is no question that Weingart influenced my ideas, but the difference was that whereas he still functioned intuitively, in an American context I had to develop a methodology for teaching. And this idea if having to have a method eventually influenced Weingart too. Then in 1972 I brought him to America for the first time for a lecture tour.

The first publication of these attempts to develop a teaching methodology for demystifying the New Typography was in the journal Visible Language (vol. VIII, no. 2, spring 1973) which showed work by Yale students from 1969-70. The most significant theory to come out of these studies was the discussion of readability and legibility, which is still appropriate today. Our revolt in the 1960s against orthodox Modernist typography coincided with the transition from metal typesetting to phototypesetting. All the givens inherent within metal type were open to question, even though the old terminology remained. What we didn’t have then was direct access to the new technology. In my book I stop using the awkward term ‘readability’ and refer to it instead as ‘unpredictability’.

PR: Can you explain these definitions?

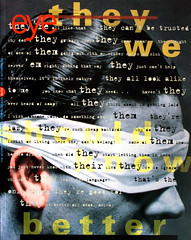

DF: Legibility is based on order, convention (predictability), simplicity and on the reader as a passive recipient. Unpredictability is the ability of a design to attract or seduce you, in an intense, virtually cluttered world, into reading it in the first place. It is usually based on disorder, originality and complexity. In the Yale project, for instance, we used weather reports designed in a number of variations to convey a message in order to explore some of the possibilities between these two extremes. I believe this is the essence of the issues that are still being debated today. It is also an example of the importance of developing theory to go along with practice – if you can describe it, you can understand, teach and use it better.

PR: People who find the current visual language abhorrent probably want to go back to Emil Ruder’s typography and pure Modernism.

DF: That is the typography which was pervasively appropriated in corporate work in the 1950s and 1960s. But I suspect the excess of the 1980s may turn into restraint in the 1990s. We should also look at the influence of Hofmann, who saw communication as more pictorial, with letterforms regarded as symbolic elements. His typography was always neutral and never the primary means of expression as it was for Weingart. That restraint had an influence on me then (as well as now).

PR: When did you first meet April Greiman?

DF: I had been in Basel four or five years earlier than Greiman, who knew of my work at Yale through Weingart. I met her, as you did, when we were teaching at Philadelphia College of Art in 1972. She replaced me at PCA when I could no longer continue to commute by air every week from Yale.

Clearly we all influenced each other. At that time there were few people interested in sharing new ideas about typography and design theory. Back in the early 1970s, even in Philadelphia, there was an incestuous Basel influence. Even more than Weingart, Greiman approached her work with spontaneity and intuition. In our relationship between 1972 and 1977 she opened me to her spirit and her way of thinking with the heart, while I probably influenced her by relating design to broader theoretical or cultural issues and seeing typographic compositions as metaphorical environments.

PR: How did you make the transition from teaching to the corporate design world?

DF: After Yale I went to the State University of New York in Purchase, where I had the opportunity to develop a visual arts programme at a completely new school. My concept required students to major in a generalised visual training (analogous to our college liberal arts programme) and minor in a specialisation (painting, sculpture, design and so on). This was the opposite of most schools, where students would specialise too early, and in my opinion be unprepared for the hybrid professions arising in practice. But the programme was misunderstood by the bureaucrats, so I became frustrated and anxious to practise professionally in a bigger way. I knew two things: that I would return to teaching one day (as I am shortly about to do at the Cooper Union, New York) and that I had an uncontrollable urge still to be a teacher, but as a practitioner. Just as I was getting these urges, I was offered a job as senior designer on the Citibank identity by Anspach Grossman Portugal in New York. So in 1975 I moved to New York City.

PR: In ‘Throwing out work from the 1970’s’ (TM, January 1981), you turned your back on corporate design and threw out highly personal graphic work. Were you unhappy with your graphic style?

DF: In the 1960s and into the 1970s the high point of what a graphic designer could do professionally was corporate identity work and maybe posters. The status of corporate projects was reinforced by our greatest mentors – Paul Rand, Lou Dorfsman, Ivan Chermanyeff, Tom Geismar, and so on. These large systems of design had a pervasiveness, had levels and factors of implementation no other project could have. At the same time, New Wave experiments were becoming a style, and I have always tried to move away from being associated with style. So after some time I came to believe that neither of these was the ultimate manifestation of what graphic design can do. While practising it I began to have second thoughts. Eventually I left Anspach Grossman Portugal, where I was doing heavy-duty corporate work, and struck out on my own, doing softer work for friends and small businesses in New York. I found the agenda of corporate projects too predictable – often you were solving the same problems with the same solutions over and over again. After all, how many ways can you design an annual report?

This was the beginning of something that has persisted ever since, except for a period from 1979 to 1982 when I became involved in helping Colin Forbes set up the New York office of Pentagram. What fascinated me about Pentagram was that they appeared unlike any American design firm. They had not taken on the look of bankers, wearing pin-striped suits and fashionable ties. They had a whole other way of approaching design, they seemed more civilised. Their organisational structure also seemed quite brilliant and I was open to this after my other experiences with corporate design. I stayed for about three years, working very intensively and productively.

PR: So why did you leave?

DF: I found the dialogues between designers very limiting. I realised that the design profession defined design in very narrow terms, that there were broader ways to consider what a designer might be doing. There had to be ways of making a contribution to society that would have more profound effects than then narrow agenda out clients set for us. So I took some time to contemplate what I was doing and networked with people outside my profession. I began to live a double life – out at night, meeting non-designers, artists. I realised I was having more fun working at night in this other world, this other side of New York City. I thought ‘Why shouldn’t I have fun all day?’

PR: Is this the point at which you uncovered an interface between art and design?

DF: There was a tremendous new invigoration, openness and energy in New York after a long period of doldrums that had followed the Pop Artists in the 1970s.

PR: Is this what was behind the title of your first art exhibition, ‘Mr. D Starts Fresh’, in 1984?

DF: This was my first major exhibition, held at the legendary Fun Gallery, a home for graffiti artists, Wild Style and early hip-hop street culture. So here I was, this commercial designer of some accomplishment, hanging out with homeboys. I showed installations hand-painted objects, sometimes functional or not, the fountain you have seen in my apartments, some folding screens, abstract sculpture, the Michael Jackson television. What appealed to me was making things with my own hands, getting dirty, raw and messy. It was the antithesis of working in a clean graphic design environment. After each day of work at Pentagram I became consumed with an obsession for painting and transforming my living environment, an apartment in a typical bourgeois block. My apartment became an expression of the dilemma in contemporary society where people are unable to express themselves personally in the environments in which they live. This is how I became interested in thinking about how design can have an impact in the domestic sphere rather than just in commercial or institutional areas. How can design be of interest to a large public than the close network of designers? I wanted to communicate through the popular media, not the trade press.

PR: The Red Studio exhibition was titled ‘Post Nuclearism’. And you new book is called Dan Friedman: Radical Modernism. What are the connections between these titles and the future you envisage?

DF: I have always had a fascination with garbage, entropy and found objects. Perhaps this comes from the realisation that most work graphic designers do is ephemeral and ends up in the trash can (unless it is saved by other designers). In some sense, our visual landscape tends to be dysfunctional – often apocalyptic. Radical Modernism is a reaction to this condition.

My early art installations and furniture were created with things found on New York City streets – partly out of necessity to find inexpensive ways to experiment but also as a means to express things in culture which design denies. In the mid-1980s I switched my emphasis to making furniture, manufactured by others. I had developed relationships since 1979 with groups such as Alchima in Italy and eventually found support there and later in France with Neotu. So my furniture became more visible in Europe than in America. Just as it had taken years for radical typography to become almost commonplace, so alternative idea about domestic objects slowly gained acceptance in America, where my work in this areas is still relatively unknown. My approach to furniture is like my approach to graphic design in that I often add other messages that have nothing to do with the function. I try to break down the boundaries between art and design. Privately, I believe that there is art and there is design. But I’m doing my best to cloud the issue in order to show that design can be more provocative.

PR: Can you imagine throwing graphic design away completely?

DF: In the 1990s I’ve come back to graphic design in a big way. Typography flows in my blood and in the last few years I have been asked to do more until that work now exceeds what I do in furniture.

PR: There have been enormous changes between your graphic idiom of the 1970s and you current work – for instance Artificial Nature or Art Against Aids.

DF: When a visual idiom or style becomes so overpowering that you can’t tell the difference between one project and another, that makes me feel uncomfortable. In the 1970s, when such an idiom became assimilated into other people’s work, it lost its inherent meaning for me. I never stopped being a graphic designer, but I definitely put it in the background. I never stopped being aware of what was going on in the world of graphic design, but I was able to look at it as an outsider, which gave me more perspective. When at last I had a really interesting graphic design project to pursue, I was able to do so without all the visual baggage so many designers carry with them. I was able to enter into these new projects with an approach which I think is more appropriate to the audience, the content and our times.

PR: Hence the simplicity of your design for Artificial Nature? It is clear that the words are there to be read, the visual connections between photographs and words are direct.

DF: It goes back to that original premise about legibility and unpredictability which I tried to define in the late 1960s. Because my students and I explored extreme parameters, it could be argued that I leaned away from legibility and convention. There was tremendous potential to take our experiments with unpredictability to even greater extremes, a process still going on today. My own contribution was simply to try to define the parameters theoretically. My own typography has never been particularly exaggerated or the main event.

PR: Why do you find graphic design interesting again today?

DF: Because I sense that the times are once more like the late 1960s, especially with the concern about content and social issues and thinking of design as a part of a larger cultural context, not so driven by issues of form or self-indulgence. There are so many more voices speaking from different perspectives that it creates a situation where you can at last have an interesting dialogue, which you couldn’t when I started out. It is a chance to reconsider what and why we are designing. That’s also why I am interested in teaching again.

PR: What do you mean by ‘Radical Modernism’?

DF: Modernism is a philosophy which emerged in the late nineteenth century. It was a concern with the way people could improve the quality of their lives, using all means including new technology and design. It would be an evolutionary process and will continue as long as we are motivated to make such improvements. When the ‘look’ of Modernism was appropriated by industry and named the International Style, it lost moral authority. We should try once again to be fun-loving visionaries; we should return to a belief in a radical spirit – the idea that design is something that can help improve society and people’s condition. Radical Modernism, therefore, is my reaffirmation of the idealistic roots of our modernity, adjusted to include more of our diverse cultures, history, research and fantasy.

PR: What do you hope people might learn from your book?

DF: It is addressed mainly to students. It is more about my past and less about my future. It is a meditation on my work, changes and struggles. It offers an agenda for optimism.

Peter Rea, graphic designer, London

First published in Eye no. 14 vol. 4, 1994

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.