Spring 2009

Reputations: Ian Anderson

‘When I took a back seat to allow TDR to grow beyond me, it died; its creative spark was crushed . . . the more I took myself out of the equation to see if it could do better without me, the more obvious it became that Ian Anderson and The Designers Republic were inseparable.’

Early in 2009, cult studio The Designers Republic shocked its fans by going into voluntary liquidation. Founder Ian Anderson pauses briefly from planning TDR's ‘slimline’ relaunch to talk us through 23 years of ‘brain-aided design’.

Born in Croydon, just south of London, on Valentine’s Day, 1961, Ian Anderson was still at school when he designed his first record cover – an EP for his punk band, the Infra Red Helicopters, released on his own label, Buy These Records. In 1979, he moved to Yorkshire to read philosophy at Sheffield University and soon became a central figure in the city’s burgeoning music and club scene. When Person to Person (whom he managed) signed to Epic Records, he designed their album cover. Their ‘High Time’ single (1984) was his first widely distributed cover design: ‘I hand-drew and Letraset the design for the Epic Records art department to follow, although I had no real idea of how or what they did’.

Commissions from other bands followed, and The Designers Republic (later abbreviated as TDR) was declared on Bastille Day, 14 July 1986, in collaboration with Nick Phillips, a former sculpture student and the organ player in World of Twist. The duo’s first identity job was for Fon Records, a system of eye-searing black and white diagonal stripes that adorned the spine of every release.

TDR’s first album cover, for Chakk’s 10 Days in an Elevator (1986), financed ‘The Embassy’, a new studio in the boardroom of a former engineering works. TDR quickly grew to a team of four, and later up to thirteen, with Anderson proving an astute judge of talent (well known TDR alumni include Michael C. Place of Build and Matt Pyke of Universal Everything).

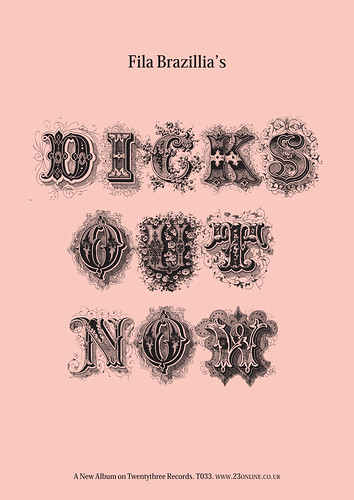

When Warp Records bought Fon, Anderson began a collaboration with the label that continues today. TDR have designed covers for Pop Will Eat Itself (PWEI), Nine Inch Nails, Aphex Twin and Pulp, among others. Non-music clients included the video game company Psygnosis (Wipeout, 1995-99), the superclub Gatecrasher (1999-2008), Issey Miyake (1999-2000), Sony (2000), Nickelodeon (2005) and Coca-Cola (1995, 2006-2007). They also collaborated on Sheffield’s Echo City installation for the 2006 Venice Biennale.

Anderson’s Pho-Ku Corporation website features extensive archives of work, press and events; the Peoples Bureau for Consumer Information is TDR’s online shop. There is even a Japanese retail outlet for TDR product: Shop 33.

3D>2D, The Designers Republic’s Adventures In And Out Of Architecture (Laurence King Publishing) was the best-selling design title of 2001 (see Eye 41). ‘Brain Aided Design SoYo’, a retrospective of their work, toured the world from 2003 to 2005, culminating in a twentieth anniversary celebration at Sheffield’s Millennium Gallery (see Eye 57).

However in January 2009, after 23 years of trading, TDR went into voluntary liquidation. Anderson bought back the company’s name and assets and TDR’s next phase is already up and running. This new incarnation will be, according to Anderson, ‘a creative-led, brain-aided, design “A-Team”’. Clients already signed include Coca-Cola, the Experimenta Lisbon Biennale and Jarvis Cocker. With control of all TDR’s back catalogue, Anderson is also busy compiling a book that has been almost two decades in the making.

Liz Farrelly: Your earliest work was made using traditional techniques, but looked like it was digital, even before computers could produce such images; you’ve called it a “faux computer aesthetic”. Were you attempting to invent the future?

Ian Anderson: Inventing the future in terms of creating a blank canvas still waiting to be written; a sci-fi “what if?”; a place where we could define the rules and warp them at our leisure, creating a sense of optimism, of technology starring as the last magic of utopia; a playground for language and ideas not bound to the here and now. That for me is the future; it’s about expectation, and now it has gone.

LF: Where did your vision of a “future” aesthetic come from?

IA: The aesthetic was a visual shorthand distilled from sci-fi films, television series, comics and books, from The Lost Planet to Doctor Who, to Gerry Anderson’s Thunderbirds, UFO, Joe 90 and Captain Scarlet. It was the moon landing and every airbrushed paperback cover for a Robert A. Heinlein or Isaac Asimov novel. It was NASA, and optical character recognition. It was everything in that realm filtered through one person’s taste, choice, vision and understanding, and presented as a consumable, digestible, inclusive visual language. We aimed to create stuff that immediately “looked” futuristic.

The inspiration, motivation, drive, starting point for my work is pop culture: why people do what they do, why they believe what they believe, what enriches their lives, and why and how that can be tapped into – what makes people tick. Then the question is, how can visual communication detonate that, and how does the role of the designer work as a sponge for information, and a projector or a megaphone to present that information in a targeted, desirable, consumable form.

LF: At one time you worried that TDR had “too tight a visual aesthetic”. What did you mean?

IA: There are times when every designer is seduced by excessive form over function. There are times when the process becomes too focused on the pleasure of doing, ultimately for the sake of doing. When we forget to ask “why?” beyond “why the fuck are you using that font?”, we lose our way. When a visual aesthetic becomes too embedded in the way we do what we do, then it restricts our ability to deliver . . . either because we lose sight of the mission, or because the [potential] client can’t see beyond the eye candy . . .

LF: You were quoted as saying: “We find it difficult to do anything simple . . . detail has almost become an obsession” (See Jim Davies’ ‘Go-faster graphics’, Eye 16). Does that still stand? Did that approach make it difficult to turn a profit?

IA: The devil is in the detail, and more is definitely more, but sometimes less is better. The detail has become less an output than part of a thinking process. It depends at which point your thinking engages with the tools and the means of expression and production. People always tell me I think out loud. I formulate and rationalise my ideas throughout a conversation, which can be quite disconcerting for new clients.

Some of TDR’s busier work was a graphic design expression of that process of looking at the job from every perspective, layering up those perspectives and content, then almost visibly, forensically dismantling the structure to reveal what lies beneath, discarding everything that is wrong, and by default leaving what is right. I don’t feel it’s so important to go through that process physically any more; the multilayering and discovery is more a mental intellectual exercise. I’m interested in simplicity right now: big questions, big ideas, global pan-cultural expressions. And, yes, because time is money, then making something work to a level I’m happy with does take more time.

LF: Sometimes you revel in surface, though, and declare that that’s all there is. At other times you’re upset that critics and fans alike don’t understand the concepts that have sparked the visual response.

IA: That’s a fair comment but the key is that TDR does revel in the surface – knowingly. And for me, if you look deeper into the language we use and how we structure it within a context, it’s clear there is something happening beyond the pure visual aesthetic. Two people tip buckets of water over their heads; one needs a shower, the other is a Fluxus member creating an intervention and making a statement. We’re all pigeon-holed, life’s too frenetic.

We don’t have a God-given right to expect someone to invest their time in decoding our work, I don’t expect it, but none of us should assume there is no value in something when we haven’t bothered to look for it. I don’t want to dumb down our messages in the work; I don’t want to make it obvious to everyone. I still believe information should be achieved and not given. I don’t complain when people don’t look deeper, I’m disappointed they don’t. I hope it’s because they have something better to do, rather than because they’ve given up looking.

LF: In relation to detail, how do you decide when something is finished? Is it often a point of contention with a client? And similarly, when the message needs to be “unwrapped”, how do you come to a consensus that a design is successful?

IA: Something is finished when we have done what was asked of us, and we have delivered what we promised. Then the job is done. If a client wants more, or we feel we need to explore the ideas further, re-evaluate the deliverables, then that is exactly what it is: more. Surprisingly, we’ve had very little contention with clients over work process and relationship during a project. I’ve learnt the advantage of developing client relationships and identifying opportunity with those clients.

In theory, the client is better placed to determine if the design is working, for them, as they should know their business more intimately than us. However, the responsibility we take on is to deliver a solution based on an understanding of the client, rather than the direction of the client, and it’s often the case that we can help them in seeing the wood for the trees. Sometimes they’re too close; we’re in a privileged position, like official biographers or hairdressers, to offer a perspective. How consensus is reached depends on the personalities involved.

LF: You’ve talked about how design should be judged in context; so, should we look at TDR album covers only while playing the music?

IA: You can look at music packaging in the context of music packaging without listening to the music. You don’t have to be doing the washing to love the Radion packaging . . . music packaging should work in parallel to the music, inspired by the same things which inspired the music, not necessarily the music itself.

LF: TDR made its name working for the music industry. Later the client list diversified; why and how?

IA: There was never a moment when I made a conscious decision to change the business; as with anything, there are push and pull factors. TDR’s work for the music industry (whether music packaging and band branding, or club and event branding and promotion) was rarely about the music per se. In some ways music has always been too sacred an experience for me to re-create and re-present visually. I’m more interested in using the inspiration for the music – the question rather than the answer – as a starting point for work intended to complement the music. It’s a vanity for the designer to attempt to do this anyway, and a lack of ambition for the band or artist to see visual communication limited to simply re-interpreting their own creativity.

For the first eighteen or so years, we never went in search of work – most of TDR’s formative work was in the music industry because that’s who rang, and at the time it was pretty good work to have. We also enjoyed working on projects in the games industry, the television and film industries, with ad agencies on one-off projects, rebranding the kids’ TV channel Nickelodeon and Telia [the Swedish telecoms company), and igniting global ideas and messaging for Coca-Cola, but it was just work that came in through the phone.

From the beginning a subtext to TDR was looking for new challenges, to alleviate the low boredom threshold at the root of much of my work, and subsequently the studio’s, too. Having kept ahead of the game in the same industry for eighteen years, especially one condemned by its very nature to forget the past and thus repeat itself endlessly, I guess I wanted to be wide-eyed about something else, find new things to say, new ways to say them, and new people to say them for, so we packed our bags and exited the safety pod.

At the same time, the financial game in our traditional hunting grounds was becoming increasingly scarce. Things ain’t what they used to be. The music industry is populated by too many people who want to be there because it was there to be a part of, they want the glory without deserving the respect. There are business people who like the look of the creative stuff and think they’ll have a go; there are young people who walk the walk who haven’t even learnt to talk when it matters.

The industry was changing long before the “devil in the download” – its privileged position in our lives was already under attack from games, fashion, consumer technology and accessible travel. Cash-rich, culture-free young people have so many more ways to burn their easy money, and in an over-crowded lifestyle market even a maximised music industry could never smash and grab the entertainment market’s piggybanks again. So, if they continued to haemorrhage marketing budgets on design, so as to shift units to a TV-dinner crowd, they were fucked. Music became just one part of people’s lives; and it was the same for TDR.

LF: So, you made the plan up as you went along?

IA: TDR began being offered, and landing, more corporate work based on our adventures in and out of modern culture. At the time, it seemed like an experiment in building up a traditional agency on cutting-edge foundations (along the same lines as the experiments with consumerism we’d conducted with the Peoples Bureau for Consumer Information and the Pho-Ku Corporation, which worked well on a creative level).

LF: You talk about consumerism, its design and aesthetic as an influence; does it go beyond shopping?

IA: I’m fascinated by the design and aesthetics of it – not specifically packaging and advertising, but the neon tapestry it creates as a whole, and how that aesthetic works, and what it means to people in the context of art, or everyday experience. It’s the omnipresence of consumer culture, the religious fervour of petty fashionistas, food fascists and gadget gurus; it’s why we’re so ready to be convinced that we need stuff we didn’t even know we wanted . . . So often consuming is what we choose to do; it’s no longer what we do with our money, it’s what we work for.

Branding in all its many direct and abstracted forms interests me, from flags designed to unify, define, represent and inspire entire nations; to football colours, and the way the official replica kit has squeezed out individual expressions of devotion, in much the same way you see with organised religion.

LF: How does this fascination with brands translate into your creative process?

IA: A question I ask is: what research should we allow to guide us when representing the personality of the brand? Few iconic brands are the result of market research, they are individual visions which tap into the market through an understanding of the market by people like me. I like smart, but I don’t like serious, even if the work has serious content, a serious message and a serious market. That doesn’t mean humour should be drained from the process totally. I like some bullshit, because it elevates meaningless existence to a higher plane; as long as you know it’s bullshit in the first place.

LF: How did you deal with the shift to non-music clients?

IA: The bigger the client, the bigger the creative opportunity; here we were adopting the same attitude, approach and art to big budgets with big prizes, and still getting the same responses from clients as we had before. Initially, it worked really well. Creativity and commerce got to know each other, firing off the novelty that both extremes held for each other.

Ultimately, it was a flawed relationship, because the business side could only sell what it could understand, and not what TDR could deliver. The volume of work meant we had to initially sprint but ultimately lurch towards being a delivery-based business rather than a creatively driven studio. We employed more people, who needed managing, so we employed managers; more people needed feeding, so say hello to the new business manager, and goodbye to the freedom to make creative decisions as to which clients to work with.

Big clients require account management, which removes the creatives from the frontline of the design process, and, suddenly, the lean-mean and super-keen a-team, making highly rewarding guerrilla incursions into client systems to deliver something special that only tdr could “do”, turned into an obese army, sucking work in based on economics and pitch politics rather than creativity.

LF: TDR moved from hijacking the logos of big brands, to working with Coca-Cola. How did that feel?

IA: I worked with some smart, funny guys in Atlanta [at Coca-Cola’s headquarters], the kind of people who would make the music industry a better place, not because they’d turn it around, streamline and rationalise it but because they care, they ask questions. The Coca-Cola personnel who wanted to work with us were fans of good design and therefore fans of tdr. They’d been given the space to stretch creatively and they looked to people like me to do it with them, because we could take them on a journey their regular agencies couldn’t [. . .] they wanted a synergy rather than a fit.

LF: You once said: “The intrusion of the soft drink manufacturer into every aspect of the social fabric of the individual is something maybe more sinister than imperialism, in that the goal is pure profit, not just 90 per cent profit” (Emigre no. 29, 1994). Do you still think that?

IA: I’m still suspicious of certain strategies by any global organisation, be it a corporation, government or religion. Working with Coca-Cola, I’ve learnt more about all three, intentionally or not, putting me in a better position to engage with the next major client. Some designers read books on typography or collect foil samples . . . I like to relax dismantling the mechanics of Capitalist Imperialism, putting them back together so we may all become better consumers.

LF: You’ve described TDR’s work as “about disinformation, because disinformation provokes more of a response than information” (Creative Review, August 2001). You’ve also said, “Our main aim is communication through design” (Computer Arts, November 2001) and talked about “dullards who dismiss our work because it didn’t conform to their narrow vision of what polite design should be” (Grafik, May 2005). Do you think you need a certain type of client to be able to create “disinformation” or “impolite” work, and did that restrict TDR to working only with “creative” clients?

IA: There is no one truth. Truth is born of arguments and contradiction; our main aim is to communicate, and I believe that disinformation often communicates more honestly and accurately than ‘information’, whatever that means. [ . . . ] I would say that impolite design is creativity, which makes the consumer of that design feel edgy, awkward or uncomfortable. I do think people should like to feel challenged, so that something has been achieved though their interaction with the design. It requires a certain kind of client who sees value in engaging with the designer on a creative level, a client who enjoys a meeting of minds and a frank, sometimes explosive exchange of ideas. Some clients aren’t a good fit because of what they do and the system they work in; and sometimes you meet the right person but at the wrong company.

LF: Why do you think that direct contact between creative and client leads to good results?

IA: It’s about being able to ask the questions at source that will provide the information for me to fulfil the brief with a creative solution. An account director telling me what the client needs isn’t enough for me to understand those needs, in the context of me giving them a creative solution. I want to know why they set that brief, or at least why they think they need such a solution. It’s about a real connection between the client and the creative, meeting them, making contact and listening first hand. It’s about the body language and what isn’t said, the eye contact, understanding the person, and getting under their skin to understand the brief. The best relationships are based on mutual trust and respect, honesty, passion, confidence and the freedom for the designer to deliver. For me, it’s important we listen to the client because it is their need we’re engaged in feeding, it’s their message, their product; and on a one-to-one level – where it should be – it could be their individual jobs on the bottom line. It is about articulating their brand, accurately and creatively delivering their message with verve and passion to inspire their market.

But it’s not just about the client; it’s about the relationship. It’s not about who pays, and who expects value for money; it takes two to tango and it takes both sides to find a workable level. The responsibility lies as much with the client as it does with the creative. And, once this relationship is established it becomes all about the idea. It is the idea and the work that needs service from all parties. I will fight a client to protect the idea if I strongly believe it is the right thing to do. I’m not always right, but I’m not going to give up without breaking into a sweat. Truth is born of arguments; doing what the client wants, when you know it’s wrong, is certainly not good value for the client’s money.

LF: Last month you closed the doors on TDR studio in Sheffield, while announcing that TDR will continue in a new format. Why do you think the expanded consultancy model failed there?

IA: Many creative companies are happy and thrive on the very model I’m lambasting. There isn’t a right or wrong way, and I’ve learnt some positive things working in a different structure. But the fact remains that most companies are made in the image of their creators, and they flourish and grow with that person or group’s personality and vision at the core of what they do. Ultimately, TDR was trying to be something it was better not being. The experiment meant that we connected with a lot of really enlightened people, who aren’t necessarily in what are perceived as the coolest businesses and organisations. It’s the people and the projects, not the products, that can make designing worthwhile.

LF: You’ve called TDR “an individual vision”. How did that work when you had a studio of up to thirteen people?

IA: It didn’t. I had a new business manager attempting to direct brand articulation, so I chose to take a step back.

LF: Is the next stage essentially just you and a small team?

IA: Yes; a small, perfectly formed and purpose-friendly team. I’m happy for it to take a little time to get into its stride, let the dust settle, find the right clients and projects.

LF: You often take criticism personally. Is that because you have a strong sense of ownership of TDR’s work – even if it’s for a client, it’s “personal work”. Is that what made it difficult for the expanded version of the company, with account handlers, to succeed?

IA: I believe passionately about what TDR does. When I took a back seat to allow it to grow beyond me, it died; its creative spark was crushed under the weight of business self-interest. I’m not saying I was blameless, it’s just that the more I tried to take myself out of the equation to see if TDR could grow better without me, the more obvious it became that Ian Anderson and The Designers Republic were inseparable. There is a strong sense of ownership and “auteur-ship” in TDR’s output. We originate and develop the creative content, direction and vision. When it works best, the end result is entirely a TDR interpretation of the client’s needs.

Looking at the work over the years you can imagine the battles fought to get the clients on side and on board, so obviously we’re going to get a little possessive, a little precious. If there’s nothing of the creator in the creation, there’s no point for anyone concerned, is there?

I’ve never seen it as anything less than a mission to communicate by any means necessary, to ask questions, to provoke responses, to engage, to create dialogue, enlighten, debate, connect, in whatever medium, to whatever audience. But it’s something that is difficult to teach people within an organisation, if they don’t already get it, or just don’t want to. I’m not saying the work we have delivered in recent years hasn’t been good, exceptional even. It’s just that the quality of the output was becoming difficult to maintain, for everyone, because of the dynamic of the set-up

LF: Over the years, there’s been talk of a book of TDR work, which would involve archiving the work. Did you ever feel that this legacy was making it difficult to move forward?

IA: I see the legacy of TDR more as a resource: it’s not a return to the past, it’s using the past as a key to the future. I don’t want to recreate what TDR was. I do want to reconnect with the principles on which its success was founded.

The reason for this is not a retreat to a “safety zone”, it’s an escape from a “safety first zone”, from a Truman Show into the glaring sunlight of the real world. When I look at moving forward, I’m more inspired by continuing to develop an approach like Fabrica’s, to develop new talent and new ideas in the context of experience, proven talent and vision, and ability to deliver, rather than importing existing talent. I’ve realised that I want to make money, to do the best for my family, but I don’t necessarily measure success by it.

Liz Farrelly, writer, editor, curator and lecturer, Central Saint Martins, London and Brighton

First published in Eye no. 71 vol. 18 2009

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.