Winter 1994

Reputations: Jon Barnbrook, Virus

One of type design’s young stars talks about his new company and the pressures of early success.

‘It was as though letterforms and stone-carved type had always existed and always would. They have a permanence and authority’

Jon Barnbrook was born in Luton, England in 1966. He studied at Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design from 1985-88 and at the Royal College of Art from 1988-90. While still a student, his historically influenced type designs and typography - and collaboration with Why Not Associates - attracted attention. He rapidly became a youthful design star, his work regularly featured in European, Japanese and US Magazines. One of his machine-generated stone-carvings is on display in the Victoria & Albert Museum. Two early typefaces, Exocet and Manson (retitled Mason after controversy) were released by Emigre Fonts in 1992-32; followed by a third, Mason Sans. Barnbrook created typefaces fro the Femidom female condom advertising campaign, and in 1993 joined Tony Kaye as a titles director for Volvo, Mazda, Volkswagen, Vidal Sassoon, Lloyd's and other clients. As a live-action director, he has created commercials for Mercury, Prudential and Hansen's soft drinks. From his earliest work, Barnbrook has used design as a platform for personal commentary, often of a political nature.

Rick Poynor: What attracted you to typography and graphic design?

Jon Barnbrook: The same thing attracts me now as has attracted me along - letterforms. Even when I was fifteen I was drawing letterforms. It may sound boring and nerdy, but I was drawn to the associations with pop groups, the romance of the relationship between the music, the typography and the images. I was doing things like copying the logos, which everybody does, then taking a song title and spending a day working with it, rather than drawing members of the band.

RP: You were trying to interpret the mood of the music?

JB: Yes, through the typography. And, as I say, the main thing that attracted me to typography was the romance of it, the associations carried by letterforms, particularly serif letterforms, and their history, as expressed, for instance, on a piece of lettering on a sculpture. That lettering has been there for a hundred years, and all sorts of things have happened around it, but it has continued to state this phrase, this truth. I like the monumentality and authority of it.

RP: Did you study design at school?

JB: No, I went to study graphic design when I was sixteen, straight from school. I did a BTec Diploma. I think I was lucky to get a technical grounding. I learned all the typography processes before the Macintosh was around. When I was seventeen, I started to learn how to use a typesetter, a Linotronic. You couldn't see what was going to come of out of it - you just had to work it out by co-ordinates. I didn't see direct manipulation of text as a way forward for typography because I wasn't that wide-ranging in my thinking, but it was certainly easier to do it myself than to ask a technician to do it for me and it was important to me even then to refine layouts as much as I could.

At Central Saint Martins I used a Berthold phototypesetter. It provided a good grounding because you can't mess about with the type too much. That, in conjunction with the letterpress, gave me a bit of respect for type. I still hate things like stretched type. You have to redraw things to get the proportions right.

RP: What kind of work were you doing at Central Saint Martins?

JB: Having just finished a vocational diploma, the first year there was pure freedom, a return to painting and so on. I thought then that I would become an illustrator. A lot of the typography I do is very illustrative; it’s making an image of the letterform, which doesn’t deny the meaning, but enhances it. But my passion for typography kept me doing it. Also, it was an area which would keep me disciplined in my thought processes. It seemed much easier to duck out of ‘argument’ in illustration.

RP: Did you have any sense of what you might do afterwards?

JB: No. That was why I applied to the Royal College of Art. I thought, I’m never going to get a job or anything like that, and so started to think that perhaps I could survive on my own. I could just work at home, and I wouldn’t particularly care if I made much money or whether the work was high profile. It would just be me doing my work, which would make me happy. Going to the Royal College was good because I’m not very confident and it gave me much more confidence to say yes, I’ll go out on my own. It was quite difficult in the end because I didn't get any work after college for quite a long time, but I survived.

RP: The first typeface you design was Prototype?

JB: It was Mulatto, an early version of Prototype, designed in 1987 while I was at Central Saint Martins. The Macintosh software wasn’t sophisticated enough for me to do it, so I just collaged it together from bits of photocopies and what have you. It was before the Macintosh hit typography. I was trying to break down the difference between serif and sans serif, which was a reasonably new idea then. The ability to import fonts on the Macintosh means that a lot of people are doing it now.

RP: What sort of response did you get?

JB: “It’s nice.” That was about it. At the time, type design seemed to be a real craft that as a designer you just didn’t touch. But seeing things like the bland ITC cut of Garamond, and then seeing the beautiful original cut, made me want to start investigating letterforms, to find out if I could get closer to what I thought was beautiful typography, or good typography. Through the summer holidays, I thought, why don’t I draw them myself? I didn’t imagine doing anything like a really big text face though because I didn’t have the know-how.

I went back to typefaces in my second year at the Royal College because a font program I thought was reasonable, FontStudio, had come out. But I seemed to be the only one interested in it. There still aren’t many in Britain designing typefaces. There are a lot of students, but I don’t think many continue after college. It’s a very tedious, boring process, constantly reshaping characters or sitting there doing endless kerning.

RP: Why do you do it?

JB: It’s the initial idea, like anything else. You discover something, perhaps by accident. Or you have a concept for a typeface and that’s what drives you on to finish it. There is also a need for control, wanting to control the look of things absolutely. I’d always been concerned with the layout, but in designing letterforms I was taking it a step further. And, of course, after that, wanting to control the content. Gradual stages of totalitarianism!

RP: Do you abandon many faces?

JB: Some of them don’t see more than one character. Or I work on four characters thinking it might be a valid idea, then it doesn’t work out. There’s one which I started about three years ago, which I’ve gone back to, and hopefully I’ll manage to make it work, though it has gone in a completely different direction. The most difficult thing with the Macintosh is to develop the drawing once you’ve got an idea. The font tools are too technical. They don’t lend themselves very well to less modular ways of designing fonts. I’m still quite traditional and I think about letterforms in terms of a brush or chisel. Most of the strokes and the unusual parts of the letterforms are created in that way.

RP: You became a fledgling design star while still a student at the RCA. How did that come about?

JB: I was working at Why Not Associates because they had seen my show at Central Saint Martins and one of them, David Ellis, was a tutor at the RCA and offered me a summer job. I went there and they were interviewed for Direction Magazine and they talked about the Next Directory, which I had worked on. Of course, I just sat in the background. Then Direction phoned up to say they would like to do an article on me when I left college. I didn’t actively seek publicity, but the reaction of the other students was weird. Some didn’t care, which was the best attitude, but some got quite jealous. It’s very easy to get it out of proportion – it’s only graphic design.

RP: In the 1980s the star-making process really accelerated. There you were, still a student, still with major decisions about what to do next to make, and someone wants to write about you. How did you cope with the pressure this imposed?

JB: I always thought I didn’t deserve it. People would phone up and ask my opinion about things before I had very much experience. There was a worry that I was flavour of the month, but I hope my work shows that it’s not just a fashion thing, that I have an interest in historical typeforms and a commitment to putting some kind of argument to work.

It could have gone the wrong way and everything could have become self-conscious. I think if you get a lot of exposure, then part of your ego can become addicted to it. So I just had to sit back and say, well it isn’t actually very important; what is important is the work, the process of doing the work, and enjoying it. If people phone me up, that’s fine, if they don’t, that’s fine too. I think constantly worrying about press exposure can be to the detriment of the work. After all, that’s not what graphic design is about.

RP: How soon after this did you start talking to Emigre?

JB: The dates of the typefaces in the Emigre booklet are wrong. Manson was designed in 1992. Exocet, designed in 1991, came from my interest in historical letterforms. I saw some early primitive Greek letterforms and they struck me as beautiful. Since they were virtually unknown, I thought I should use them in a typeface.

I had designed four or five typefaces and I was sure somebody would be interested in them, so I sent them to FontShop. They wanted to release three as one package but I thought the fonts were worth more than that. Then I was in California so I went to see Emigre and they were very positive about it and things moved very quickly from then on.

RP: Soon after college you said that you didn’t want to publish your typefaces because they were for your own personal use. What made you change your mind?

JB: I decided I was being too anal about it and should let people use them. I’ve seen them used on some dreadful things and my first reaction is horror, but then I laugh. I saw Manson used on an Emerson Lake and Palmer album yesterday, which is probably the lowest of the low. Manson has also been used on some Alice Cooper album as well. Pretty sad.

RP: Those art directors are zeroing in on the font’s gothic quality.

JB: Yes. But the gothic reference is to the history of type, the gothic letterform comes from a broad-nibbed pen. I’m sure when I release Bastard it will spread like a disease on heavy metal albums.

RP: Do you ever see the faces used in more sensitive ways?

JB: Not really, but then I don’t think I’m the best person to judge. Once you’ve designed a typeface it becomes a finished thing, and though it’s mine, I always feel disassociated from it when somebody else uses it. But I don’t like it when people squash them. They’re not meant to be squashed.

RP: Emigre had an extraordinarily angry response to Manson, with scores of complaints and a mention in Time magazine. Why did you give the typeface that name?

JB: I was really surprised when people complained. The name had become the typeface. A name is used so much it becomes abstract. The name it has now, Mason, is exactly the opposite of what I wanted. The typeface was taken from drawing I’d made in various cathedrals and from letterforms I’d seen, and calling it something as obvious as Mason, which related to stone-carving, makes it too cosy. It was designed in the 1990s and it should acknowledge that. We live in a world that is far from cosy.

It is called Manson because of the sound of the word. It sounds elegant: elegant typeface, elegant name. But then, hopefully, you do a double-take, you think, Manson, where does that come from? He’s a mass-murderer. It wasn’t that I think Charles Manson is great, or that I wanted to glorify somebody who murdered people. I was trying to make you…not only look at the typeface differently, but consider its context differently. I don’t know if that sounds thin, but that was the intention.

RP: When you licensed the face to Emigre, did you have any idea of the way Manson’s name would be perceived in America? It’s like naming a typeface after the child murderer Myra Hindley in Britain.

JB: It is, but when I designed and named it I had no idea that it would be released. It was designed in Britain, and two or three years ago a lot of British people hadn’t really heard of Charles Manson.

RP: Did you realise that for a certain disaffected subculture, Manson is a kind of anti-hero?

JB: Not at the time. Now I know more about him, that’s quite attractive. Not in a culty way, because I’m not interested in violence, but I am interested in that kind of anti-hero. I’ve been toying with the name Lord Haw-Haw [Second World War mouthpiece for Nazi radio propaganda] for a typeface, because he’s the ultimate British anti-hero.

RP: The sense of unease you talk about, the double-take – it’s not as though there’s anything especially uneasy about the face, or is there?

JB: I don’t think it’s a solely retrospective face. Some of the characters are quite modern. I think it does look dangerous in a way. Some of the letterforms are quite sharp and nasty. It’s the paradox of something both beautiful and ugly. And in a terrible way, to be very cynical, it has enhanced my reputation.

RP: What do you mean when you cite “Englishness” as one of your inspirations?

JB: I have to be careful about this because whenever people say “Englishness”, I worry that they think I’m patriotic, which I’m not. Patriotism is one of the things I hate. I’m interested in different cultures, but I think I should do work which is appropriate to my own. One of the things I disliked most when I was younger was the American influence on everything. There is not getting away from it and it’s only natural to rebel against it.

The typography I liked came from England. Mason Sans, my latest release from Emigre, relates to Johnston. It’s an English sans serif that’s very much in the tradition of Roman sans serif, which Johnston started. Johnston still, I think, one of the most interesting and valuable typefaces. The letterforms which have most influenced me are those I discovered outside the type archives. Walking past a Post Office there would be a bit of type that had been there for 50 years. Nobody knows who did it, but it would be incredibly beautiful, because of its associations.

RP: Your use of the cross has become almost a personal trademark. What is its significance?

JB: It’s just a simple, extremely meaningful form. Two lines. It’s one of the most interesting graphic design symbols in history and you experience a mixture of emotions when you see it – all hypothetical things, love, hate, misery, fear. It is both modern and old, taken up by the Russian Constructivists as part of a new political ideal, but also representing the establishment in a non-communist world. Why is the cross in the middle of the Next Directory? You can make ironic associations. But I’m not religious at all.

RP: You’ve talked about the authority you seek in letterforms.

JB: Speaking on a personal level, my mother has been married three times, we moved house every year. You need certain reference points in your life that are permanent. It may sound odd to say it, but letterforms and stone-carved type – it was as though they have always existed and always would. There’s a permanence and authority there. They will be there whatever happens. And despite the Macintosh coming along, I think print still has that authority.

I’m not interested in getting any power from graphic design myself. I find that sort of thing very dodgy. I’m not interested in setting myself up as an authority. But I am interested in playing with the idea of authority and making it work against itself, to destroy it. This is the reason for calling a typeface Bastard, to highlight fascist associations and work against them. The tension between authority and its destruction is a constant theme in my work.

RP: You are very much a designer of capital letters. Why the reluctance to produce lower case alphabets?

JB: Capital letters just seem more beautiful. But recently I’ve designed a typeface, Prozac, that’s all lower case. And I have a few text faces which I’m working on, but it takes much longer. I used to have a problem with lower case, but now I don’t. There is also the Modernist idea that everything should be set in lowercase, that it’s more readable, which I think is rubbish. There are many different kinds of reading.

RP: So you resist that kind of European Modernism?

JB: I have nothing against being European. But at college the Modernist police would come round and say, no, no, you can’t read that, you can’t do that. Actually, when I think of Modernism, I don’t think of typography, I think of architecture and horrible buildings that don’t relate to people’s lives. I want a bit of humanism in there. Although I talk about the authority of the letterform, I want the work to have a personality and I find the notion of Modernism too restrictive. I still agree with the socialist side of Modernism, but I think Modernism has been given a much bigger position, centre stage, than it deserves.

RP: You have said that socialist principles underlie your work, and you sometimes sound quite cynical about what graphic design does. Yet you work increasingly in advertising.

JB: I’m only sceptical about what graphic design does in the context of what it serves, which is a capitalist system geared towards production for profit rather than for need. Which is a ludicrous way to run any society. Once you reach this conclusion, it makes it hard to do good work for anything. So in that sense I’m very cynical. On the other hand, some people have made very black and white statements about advertising which I don’t agree with. They seem to think that if we didn’t have advertising, we’d all be living on the bare minimum. I think that advertising furthers people’s fantasies and even helps them to have them. Everybody needs some kind of fantasy and theatre in their life, and advertising is part of that.

Not everything I do has an ideology behind it. I’m not ashamed to admit that I do work for money, because it means I can go off and design a typeface for a week, or whatever. I do things for different reasons. One of the main reason I do a lot of advertising work, although I’m concerned to do a good job, is to generate money to finance the font company I’m setting up. And one of the reasons I’m setting up a font company is so I can say exactly what I want in the promotional literature that’s sent out.

RP: A lot of your personal work, where you have complete control, makes strong political and social statements. You used the Illustration Now annual, a commercial project, as a kind of visual essay. How do you justify this?

JB: Most of the time the message isn’t worth saying. So when you do get a chance to say something yourself, you might as well say something you believe in. My design work has changed a lot. If you compare the Next Directory and Illustration Now, the Next Directory is a series of nice layouts, and there is a bit of irony in it, although it’s not obvious, whereas in Illustration Now every picture and layout has a meaning and there is a reason for everything being there. That’s why I find it irritating when people call me a stylist. There’s a reason for the way I do things and if you look I hope you’ll get the meaning, though the communication process isn’t so direct that you are necessarily going to get it the first time you look at it.

I don’t like the phrase “self-indulgent”. Illustration Now has been accused of that, but I think that’s a marketing ploy, because if you get somebody to do something self-indulgent, it sells the product. I’m quite aware of the political paradox. In the end, it’s a product. That’s why Illustration Now is covered in pictures of beans – it’s a commodity, like everything else.

RP: How did your involvement with Tony Kaye Films come out?

JB: He just phoned me up and said, “Would you like to do typography on this commercial? It’s about nuclear power.” And I said, “No.” Then he phoned me up again and said, “Look. I really need somebody to do it.” And then I started to think about the idea of nuclear power and the idea of hypocrisy in graphic design, and in the end I did it and donated half the money to charity. That’s not because I was trying to ease my conscience. As a designer it was interesting to see how far you can disconnect yourself from you own point of view. I got a real sense of pleasure from doing something absolutely opposed to what I believe in, which is quite weird. I won’t show people the commercial now because I feel embarrassed – people won’t believe why I did it. Some people think I have no ethics at all, which is the Manson name syndrome again.

That was the first thing I did for Tony. I’m really glad I work with him because of his passion. He’s exciting to be around. And he said, “Why don’t you start directing?”

RP: Had you thought about directing in the past?

JB: I’d done a few animations, but otherwise, not at all. The reason I carry on doing the advertising – apart from the money – is the process of working with other people. I get the creative release through the typefaces and my own work and the social release through advertising. Direction is a completely different tangent, the opposite of the static nature of my typography. Being a good director is not about being a visual trickster, it’s not about moving people emotionally. When I first started doing it, I thought, I’m going to leave typography to do this, but I still think I have a lot to say in graphic design, so I’d like to carry on with both.

RP: What do people in advertising, like Tony Kaye, want from your typographically?

JB: They think they’re getting something that is in sympathy with the live action. That helps sell the product, directly or indirectly. Or sometimes with Tony I’m adding something else, a completely new meaning, references to design or film, experimental things which are completely over and above what the commercial is about.

RP: Does he talk to you about what that meaning might be?

JB: No, because he’s so wrapped up in his own conception of what the film is about. He doesn’t say anything because I’ve worked with him a lot and he trusts me. He says, just do something. Often I don’t see the live action and I just have to do it. Although he’s really passionate, he lets it go enough for me to do that. When I do advertising, I can’t think about any of the personal things I want to pursue. I just think, what would be an elegant piece of typography for this, or how do I put over the message? Although inevitably it comes out looking like a piece of my work.

RP: When did the idea of a typeface company come to you?

JB: When Emigre told me they had changed Manson’s name. I had taken six months off and was uncontactable and they did it without even asking me. It was the first time I had encountered a situation where somebody else had control of one of my typefaces. So I decided I might as well release them myself. Although I’m no longer a student, I always feel like a very small person in a very big area and I think it would be nice if I was an example to other designers, and could do this on my own, without a great deal of money, and have some kind of influence. The literature for it will state exactly what I want to say.

RP: You mean there will be some kind of social or political comment?

JB: There will be. I keep coming back to the fact that it’s only graphic design, which, like pop music, is very ephemeral, yet it is important at the same time. I’m not sure if I will release other peoples’ fonts as I don’t want to be an administrator. I don’t care if I don’t make any money from it. That’s not the point.

RP: Have you got a name yet?

JB: Yes, the VirusFoundry. It came from the typeface I call Virus. I don’t know if that’s a corny name, but I’ve thought about it as much as I’ve thought about the typeface names – they often go through four or five changes before I stick with one. The word virus has very different meanings. First, the idea of something subversive being on a computer. Second, viruses are organic, which is paradox on a machine. Third, the political implications – “virus” is a metaphor for paranoia, like the “virus” of communism in the 1950s. It also seems a very 1990s word, because it links with AIDS, and with the end of the century. According to some radical and misguided Christians, AIDS is supposed to be part of the apocalypse.

RP: How many fonts do you intend to release in the first batch?

JB: Ten or 11. When I went travelling, one of the things I did was to draw letterforms all day. It’s going to take ages to finish because I have to fit in around other work and I’m trying to kern everything properly. I think the typefaces embody contradictory ideas of beauty and ugliness. Mishima stated that all extremes are similar, and I hope people see a kind of argument when they look at my typefaces. Prozac is the most recent. It’s an experiment with lower case – the Modernist idea of simplifying the letterform down to the very basics. The manufacturers of the drug Prozac claim it has no side effects, but there is a group called Survivors of Prozac which includes members who have allegedly committed heinous crimes while on Prozac.

RP: There are several strands to your work as a designer. But is this the central one – you draw type?

JB: I never thought it was, no. I always thought of myself as a graphic designer, but people seem to see me more as somebody who designs typefaces. I think perhaps I put more of myself into the typefaces. People never talk about the enjoyable process of designing, they always concentrate on the intellectual side of problem-solving. But I think it’s fair enough to do a piece of design which is an enjoyable process for you as a designer. And that’s what a lot of these typefaces are. I don’t design them necessarily to sell, or even to use them myself. I don’t think about the audience at all when I’m doing them. What I think about is the process that goes on between me and the typeface.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, London

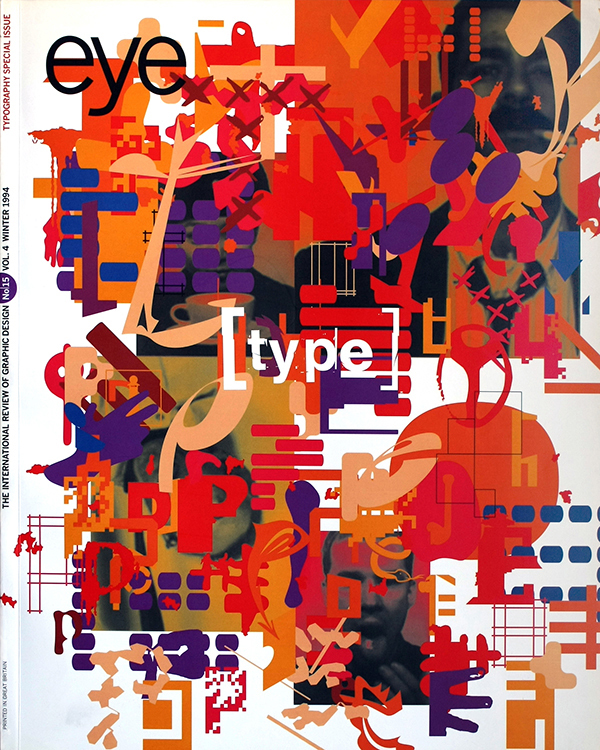

First published in Eye no. 15 vol. 4 1994

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.