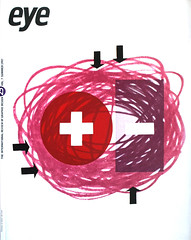

Summer 1997

Reputations: Milton Glaser

‘I am nervous about ideologies, whether it’s the ideology of business or the ideology of Bolshevism. I get nervous in the presence of absolute certainty’

Milton Glaser was born in New York City in 1929. He studied at the Cooper Union Art School in New York and won a Fulbright scholarship to the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna. In 1955 he co-founded Push Pin Studios with Seymour Chwast and Edward Sorel. As an illustrator and designer Glaser helped alter the course of American graphic design. In an era dominated by Swiss rationalism, the Push Pin style celebrated the eclectic and eccentric design of the passé past while it introduced a distinctly contemporary design vocabulary, with a wide range of work that included record sleeves, books, posters, corporate logotypes, font design and magazine formats. His pictorial eclecticism left a mark on a generation – so much so that his leaving Push Pin in 1974 was as significant an event in the design world as the Beatles break-up was in popular music. But Glaser had broader horizons. He was a founder of New York Magazine (as well as its ‘Underground gourmet’ – writing about good, cheap restaurants in New York), and publication design had become a big interest. Setting off on his own he founded Milton Glaser Inc., which devoted itself to multi-disciplinary design, including restaurant and supermarket design. A recent client is the Starbucks coffee-house chain. With Walter Bernard (former art director of Time) Glaser co-founded WBMG, a studio dedicated to magazine and newspaper design work. At the same time he turned his attention to painting and print-making. In addition, he has taught a design class at the School of Visual Arts (SVA) in New York that has been one of America’s most respected programmes for over 30 years. Glaser’s magazine credits include Paris Match, L’Express and Village Voice.

Top: poster insert for Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits album, Columbia Records, 1966.

Steven Heller: How has the design field changed since you entered it over 40 years ago?

Milton Glaser: The most important change is the acceptance of the fact that design is an absolutely essential part of the process of business, and consequently, that it is too important to leave in the hands of designers.

SH: Do you mean that designers have reverted back to service personnel?

MG: How to communicate is determined within organisations significantly more than it was when I entered the field. The design process has now been integrated into a client’s control system, so that instead of going outside for people who had more understanding about how to communicate effectively, they now make their determinations from a marketing point of view and then, more often that not, go outside to implement those ideas … Clients now have a much greater preconception of what they want. The briefings are very different. The determinations of what is appropriate are very often those of a marketing department as opposed to the somewhat casual and random solutions that occurred when people didn’t know better.

SH: So are you saying that before design became as sophisticated as it is today, the designer had more licence to play and experiment?

MG: In a way. An intense professionalisation has occurred, and a hardening of the authority between the client and designer. In the old days, clients would go to somebody like Paul Rand with the hope he would invent the form that would communicate what they were not imaginative enough to communicate. Today, they go to a designer and say, ‘These are our objective, this is the vernacular we hope to use, these are the key elements to be expressed’, and so on.

SH: Do you think this new-found literacy is a result of there being too much professional design?

MG: Well, part of it comes from the professionalisation of the practice and the fact that there are more people who are more experienced at doing this than ever before. A consequence of this professionalisation is that accidents don’t happen as much and there is more conformity based on the previous success. Accidents are often the opportunity that people have for expressing ideas and personal vision.

SH: Doesn’t this contribute to an underground that subverts convention or, at the very least, finds alternative ways of expression through design?

MG: Sure. But it is very important when you talk about design to realise that it is so highly segmented today in terms of objectives and activities that there is no general definition that applies to the whole field. Those who are outside the commercial system – who don’t have a practice that helps people sell goods, and use design as a kind of theoretical enterprise – are on a different track. Design can certainly be subversive when its subtext is to undermine the assumptions of a political or social system, not to mention an artistic one. Frankly, I am nervous about all ideologies, whether it’s the ideology of business or the ideology of Bolshevism. I get nervous in the presence of absolute certainty.

SH: You have admitted that your impetus for becoming a designer was, among other reasons, to bust the Swiss canon which was dominant in the 1950s. Wasn’t that ideologically subversive?

MG: Every emerging generation has to find something to fight against. You have to struggle against a resistant canon in order to move towards something that is your own. I understood that the idea of Modernism and the Swiss School was a great theory, but I also understood that I couldn’t adapt to it or do it as well as the practitioners who had already mastered it. So I knew that I had to go elsewhere. And when you go elsewhere, you end up challenging the larger idea. A single way of doing things seemed too doctrinaire, too limiting, when there was so much beauty, so much excitement, so much potential in what the world had already offered. Curiously, [Push Pin Studio’s] post-historical efforts were to find out what it was in history that was an interesting as Modernism.

SH: Was that a conscious decision?

MG: Part of it as a sense that [Modernism] was used up. As the Chinese say: ‘Everything at its fullness is already in decline.’ We were looking at stuff that we had seen for many years, and it wasn’t going anywhere, it was not improving on the original model. It seemed to have limited people’s opinions enormously. It’s not that you couldn’t do beautiful work within the tradition – and people still do – it was just that in terms of its expressive potential, it seemed to me it had reached its fullness.

SH: How would you contrast what you set out to do back then and the rebellion that has occurred in design over the past decade?

MG: It’s different in one respect: my great models for what to do were largely historical. For example, I felt that Art Nouveau had an extraordinary reservoir of ideas contained within it that I could still use. I looked at Charles Rennie Mackintosh and realised how compelling his ideas were, and how he helped set the stage for the Bauhaus. In other words, why use the Bauhaus as your only model, as the Modernists did, when you can see the Arts and Crafts movement, and mackintosh, Ruskin, William Morris, Frank Lloyd Wright, the Viennese Secession, as well as the Bauhaus as a continuing series of linked ideas?

SH: I want to understand what you mean by ignoring history. For example, David Carson, through Beach Culture and Ray Gun, is indicative of one aspect of the experimental phase of contemporary work. He appears to be pushing the envelope, rather than simply ignoring history. Do you think this work lacks historical framework or understanding?

MG: No, I wouldn’t say that. In trying to broaden the role of typography these experiments are ultimately beneficial, although a knowledge of Dada and Russian Constructivist typography would enrich the inquiry. To some extent it represents the same kind of response to a rigid system that serves to energise people by searching for alternatives. On the other hand, it seems to me that if you are going to be a revolutionary, it is best to be an informed one.

SH: Is historical ignorance really detrimental? Don’t we make our own historical context?

MG: When I went to school, Abstract Expressionism was in its ascendancy and most of the students began painting in that way. One of the great attractive qualities of avant-garde work is that you put yourself in a position where you can’t be easily criticised because one can always say that the critics don’t understand the new value system. One of the great attractions of doing Abstract Expressionism for a lot of ordinary kids was that they could not be judged!

SH: And the consequences of that?

MG: The consequences were very sad, because once Abstract Expressionism had passed, the adherents were thrown back on their resources, and those who were not trained had nowhere to go. I think that analogy may hold up today. The attractiveness of working in the manner of today’s expressionistic nihilism is that it looks cool and explores new territory. The bad part is that its surface qualities can be easily mastered without discipline or understanding. It celebrates the decorative and the expressive at the expense of other things.

SH: What are those other things?

MG: Structure, clarity of intent, form history – all the things one traditionally needed to make judgments. Design is about making judgements. How can you train people to judge what is good, what is bad, what is meaningful, what is fraudulent, if they don’t have the understanding of what those ideas have meant historically?

SH: How did you learn?

MG: Partially by studying history, living in Italy, learning how to draw academically. Staying curious. I also was fortunate in that my practice has been a broad one. But it hasn’t been about ‘effects’, and it wasn’t primarily about how things looked when you subject them to the astonishing capacity of a computer and so on.

SH: How has teaching changed since you began?

MG: many design teachers don’t seem to understand the degree to which the nature of the audience is really the pre-eminent influence on design. The focus in Art School is often on me-me-me and ‘my’ expression and ‘my’ vision and ‘my’ career, linked to the delusion that if you reveal your soul, people will be willing to spend money for it.

SH: How do you teach?

MG: Well, I try to be very specific and propose that every problem starts with the same questions: ‘Who am I talking to? Who are these people? What do they know? What are their prejudices? What are their expectations?’ etc. the three cardinal rules of Design are: Who is the audience? What do you want to say to them? How do you say it effectively? If you don’t follow this sequences, you’re always going to make some terrible mistake.

SH: Then were does the personal expression fit in?

MG: If fits in the cracks – because the drive to express things personally is so profound that no matter how objectives the rules, good people want to make it their own! But given the choice between making it your own and not communicating versus communicating and not making it your own, there seems to be very little question about which is the more appropriate role for a designer.

SH: Have your students changed considerably over the past ten or fifteen years?

MG: I generally get people who choose to study with me, which suggests that there is something in my work that they already value. So it’s a little difficult for me to say that my students are different. They are different in the sense that most of them literally cannot work without a computer.

SH: Are you tolerant?

MG: They can work any way they want, as long as they are thinking straight. Personally I find it regrettable that people no longer have the skill to address even a simple problem without the computer. There is no way of preventing its use at this point, since even the most rudimentary drawing skill seems to have vanished. Drawing skills are not about becoming an illustrator. The most fundamental way of understanding the visual world is through the act of drawing. When you are about to draw something you become attentive to its appearance (and sometimes humble before it) for the first time. I know of no better way of preparing yourself for a career in the visual arts. That said, I can’t imagine why it has virtually disappeared in the education of young designers except for the fact that it requires consistent devotion and practice. The Italian word for the design and drawings is the same, disegni. As usual, the Italians know something about the subject.

SH: Do you think that reliance on the computer has somehow impaired the thought process?

MG: Nobody clearly understands how the use of the computer changes the nature of the way you think. I believe that it does. One way it does that most profoundly is that it gets you much more interested in ‘effects’ than in content.

SH: Given that design schools have so much to teach in a short time, how does one avoid the quick and easy answers?

MG: The question is: what should people be teaching at school, and what is the basis for visual understanding? If you don’t have the bedrock of understanding, you will become a victim of style.

SH: The paradox is that this field feeds on style. And clients are coming to the designer looking for style. It seems a vicious circle …

MG: In personal terms the question becomes: should you follow each passing style to stay hip and on the cutting edge, even when you recognise that the style of the moment is transitory and trivial? I suppose this question is no different than how you choose to dress at a particular moment in time. One of the social roles of fashion is to define generational difference. I assume the same rule applies to the world of design. I would be embarrassed to imitate the work that is fashionable now for the same reason that I will not wear my old bell bottoms when the style returns. The most style-conscious designers inevitably find themselves in a dilemma when the style that made them famous is no longer of the moment and begins to recede. The larger question might be: how can you retain your interest in doing what you are doing for a lifetime? How do you stay in this field without becoming a service provider?

SH: So how do you do that?

MG: That’s the struggle that every old professional has had to deal with. I’ve had a long career. How do you stay relevant in this field if the assumptions change? I tried to broaden my understanding so I could do more than one thing and develop new ways of working that didn’t resemble the work I became noted for in the 1960s and 1970s. The mouldy smell of a previous decade can destroy you.

SH: Let me ask you, then, about Starbucks, the chain of American coffee-houses. Consistent with their retro-based corporate identity, they hired you and Victor Moscoso, among others, for your historical or nostalgic style. So do you reject the offer because it makes you into an oldie but goodie, or do you accept it because it’s a good paying job?

MG: That’s a good question. When they gave me the job I had to consciously try to replicate an old style of mine. It was hard for me to do it. I couldn’t do it very well in any case. But in this case doing a self-parody seemed okay. I’ve been doing very different work in recent years, and people who know anything about my work could recognise the distinction between something I might do today and a work of self-parody.

SH: Well, the cognoscenti would know. But on the other hand, Starbucks is this huge new phenomenon, building its identity on a certain kind of retro sensibility, and is appealing to an audience that does not know you, and that your work is self-parody.

MG: For this time it doesn’t matter. I didn’t think that would have much meaning to either the cognoscenti or the people in the street. I don’t approach any of these jobs indifferently, but my work has gone in another direction. I think the poster I did for the ‘Art Is’ campaign [for the anniversary of the School of Visual Arts] is much more representative of what I am doing currently, and I don’t think there is any relationship to my identification as a 1960s icon.

SH: People know Milton Glaser, the 1960s and 1970s image-maker. How do you sell clients on who you are today?

MG: I have a funny and varied collection of clients. I have an entirely different reputation as an editorial designer, for instance. With my business with Walter Bernard [WBMG], I have a lot of experience designing magazines, which is not linked to my personality in the 1960s at all because, in a sense, my hand is not involved at all, only my brain is.

SH: Is it correct to say that you can be more anonymous as a magazine designer?

MG: I think so. An ongoing professional problem is that exposure produces boredom. If your career is based on celebrity you have to be careful.

SH: Speaking of celebrity, you certainly had it with Push Pin Studios. Why did you leave?

MG: I left Push Pin because it had become too celebrated, people knew too much about it, and there was too much expectation built into that identification. I wanted to try to do something else that had no relationship to history.

SH; You confided a few years ago that your business was levelling out. Did you have a sense that the time was over?

MG: Certainly the time that I was hot was over. Actually, some years ago at the AIGA [‘Dangerous Ideas‘] Conference in San Antonio, when I looked out over the audience, I saw mostly people between 30 and 40. I realised that I had become marginal to the field. It has moved in other places. For instance, the field became obsessed about business practices, the focus seemed to be entirely about insurance, contracts, documentation, maintaining business control, dah-da-dah-da. That was never at the centre of my interests. I am not speaking critically about this change, because it has real reasons to occur. The fact is, I never ran a business in my own mind: I just put people together to help me do things …

SH: Like an atelier?

MG: Yes, an atelier. It was very important for me to have that model. The idea of business as such was something I dreaded. When we started Push Pin, it was a bunch of guys getting together and doing good things. And I must say, for a long time that really was the spirit of the place; the first ten or fifteen years we were running it like a bunch of art students trying to change history.

SH: What do you find valuable in current graphic design?

MG: The very things that you think are terrible are often linked to what is valuable. The enlargement of possibilities that exists in terms of extending expressive options in typography though the use of the computer is one example. The fact that the computer offers ways of seeing that are different and challenging is the best part of what has happened. At the same time, these powerful technologies have the capacity to be enormously valuable or enormously damaging. I suppose what worries me is that I can’t see the underlying value system that informs the work around us.

SH: In what sense?

MG: I don’t understand the way the system works now, between the critics, the magazines, the juries, the professional organisations, and so on …

SH: The design magazines have become more critical. There has been more debate.

MG: Well, I don’t think it’s so much debate as argument, which is a little different. I’m not sure whether they are about professional practice as much as they are about egocentricity or self-promotion. There are a handful of critics who are now dominating the discourse and they are linked by an amazingly similar ideology. That narrows the field of vision. I think that there are more issues in design than expressive typography, for instance. For some reason, the big hot issue in design has become typographical manipulations as well as the question of whether it is readable or not – not exactly the most informed issues that criticism might deal with.

SH: For years there was the call for a critical voice. Now that we have got it, is there a way of doing it better?

MG: More generosity on everybody’s part. There is nothing wrong with a critical dimension in our field, but it has taken a peculiar and polarising direction that doesn’t serve the profession very well. I think the role of design is so all-enveloping that it is hard to separate its characteristics critically. Is design a job that gives many people basic employment providing a utilitarian product? Is it a craft requiring measurably objective skills that should be maintained? Is it an art that can serve as a potent means of self-expression? Is it a profession whose members can influence the health and well-being of the general public? Is it a discipline that involves a philosophical inquiry into the nature of truth, beauty, and reality? Is it an instrument for social change or manipulation? If the answer is all of the above then I guess I’m looking for a broader critical voice that makes the significant differences between these issues clear – I haven’t heard that voice yet.

First published in Eye no. 25 vol. 7, 1997

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.