Autumn 2001

Reputations: Neville Garrick

‘I won’t compromise my concept. If entertainment doesn’t contain information, then I don’t want anything to do with it.’

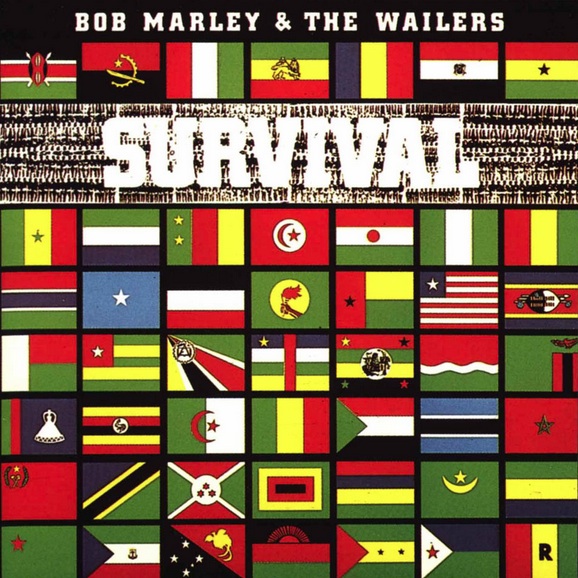

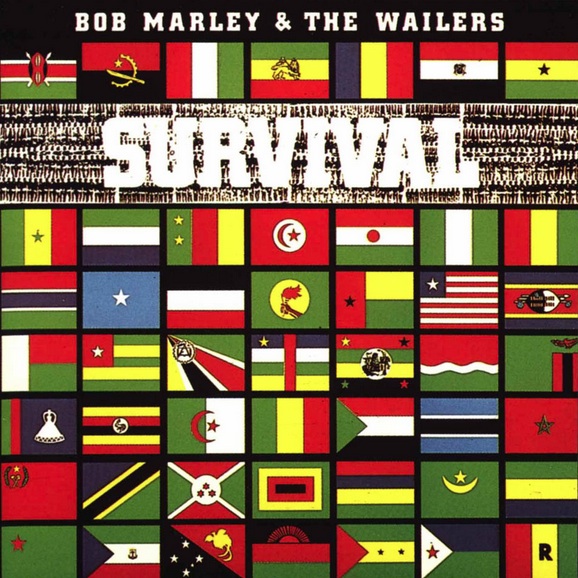

As Bob Marley’s close friend and art director during the 1970s and early 1980s, Neville Garrick created some of the most recognisable and powerful images in popular culture. While his covers for albums such as Survival, Exodus and Confrontation have played an integral role in spreading Marley’s music and the Rastafarian faith throughout the world, it would be unfair to label him solely as an album designer. Working tirelessly to promote Rastafarianism and Pan-Africanism over the past 30 years, Garrick is also political activist, author, illustrator, photographer, historian, screenwriter, musician and inadvertent A&R man (his glowing reports of a Steel Pulse concert helped the British band win its first record deal).

His professional career began in the early 1970s, when, following four years at University of California, Los Angeles, he returned to his native Jamaica to be art director at the The Kingston Daily News. Following an encounter with Alan ‘Skill’ Cole, an old classmate who had become Marley’s personal manager, Garrick soon found himself designing covers and eventually touring the world with the reggae superstar. Starting with 1976’s Rastaman Vibration, Neville created a series of classic covers, including Exodus, Kaya, Babylon by Bus, Confrontation, Buffalo Soldier and Survival. As reggae’s pre-eminent designer, he also created covers for Bunny Wailer (Blackheart Man, Struggle, Bunny Wailer Sings the Wailers and Liberation), Peter Tosh (Wanted Dread or Alive and No Nuclear War), Ras Michael (Rastafari), Burning Spear (Hail Him and Man in the Hills), Steel Pulse (Earth Crisis and Babylon the Bandit), and Rita Marley (Harambe). Currently he is working on Universal Records’ reissues series of Marley’s work on Island, including a double CD of Exodus, for which he wrote the liner notes. In July 2001, shortly after the twentieth anniversary of Marley’s death he finished a life-size hologram of Marley for the Bob Marley Museum in Jamaica.

Through his covers, Garrick has played a significant role in introducing Ethiopian art and culture to Western audiences. In 1999 he published his landmark photography book A Rasta’s Pilgrimage: Ethiopian Faces and Places (Pomegranate Press) and wrote the introduction to Chris Morrow’s own book about the genre, Stir It Up: Reggae Album Cover Art (Thames & Hudson).

Chris Morrow: Did you have any formal art training when you were young?

Neville Garrick: I never got a chance to do art until I was in fourth form. I used to draw from comic books and stuff like that, but I was in the A stream, and in the British system, when you’re in the A stream, you don’t take woodwork, metalwork, art, that sort of thing. You do physics and chemistry and biology. But I dropped French and Latin and that’s how I got time to join one of the art classes. That’s how my training started, when I was fourteen.

CM: How did you first get involved in graphic design?

NG: My parents wanted me to do business or medicine. They would say, ‘Artists are always poor.’ So it wasn’t encouraging, but I had a set mind that I wanted to do that and I ended up going to the States. They had an art school in Jamaica at the time, but it didn’t really have a graphic design programme. And I didn’t want to do fine arts, though that was my first training. When I entered UCLA at the end of 1969 I had to list my major as economics, because there was no room in the art department. I took a few art courses and got As, so the next semester they had to accept me.

Then I started being one of the editors of Nommo, which was the Black student daily. There I could apply my skills in design on the cover, things like that. I started doing political posters. One of my first was of Angela Davis. I was involved in every kind of student demonstration on campus. I would do silk-screen posters for the protests, with the power fist and that all that.

CM: So how did you get yourself through school?

NG: I used painting as a way to pay my tuition. Stuff dealing with African themes, Black history, social commentary. I sold my first painting for $50, to the head of the African American studies centre and my price went up to 0. By the time I left I was getting $400 a painting.

CM: How did you wind up going back to Jamaica?

NG: I was recruited to work for this new newspaper, The Kingston Daily News, as the editorial art director. The Sunday magazine was my favourite thing. I used to design that, lay it out, I even did the paste-up. At that time we didn’t have computers, so that was exciting. I got to work in colour and I could take it from content to press. And while I was there Alan ‘Skill’ Cole, who was Bob Marley’s manager at the time, came to me to do the sleeve for Judy Mowatt’s Mellow Mood. I did that, and then he said to me, ‘Why not come work for Rasta?’ That was about 1973.

CM: Were you familiar with the Wailers at that time?

NG: Yeah, I had been familiar with Bob’s music since ‘Simmer Down’. When that came out in 1963, I was a teenager. I was always into music. But I never really met them.

CM: After the Mowatt cover, did you think you would get into designing sleeves full time?

NG: Yeah, I liked that. Before I even did that first one for Bob, I did Rastafari, the Ras Michael album, with a young picture of His Majesty [Haile Selassie]. A lot of people liked that. I resigned from the paper and went to hang out at 56 Hope Road [the Kingston house where Marley and his entourage lived during the 1970s and which later became home to Tuff Gong Records] and I kind of created my job as art director for Tuff Gong. I was never on a salary, but I would do all the labels.

The first album I tried to do for them was Natty Dread. I actually flew to England with some images that I had shot of Bob in Jamaica. He had performed with Marvin Gaye at this benefit for Trenchtown and blew Marvin off the stage! That’s the first time I realised how big Bob would be. I really got into the Wailers. That led to me doing some posters of Bob and the Wailers, black and white posters, from the photographs I had taken at the concert. I met Bob and showed him the photos and he gave me the go-ahead to do the posters.

CM: How involved was Bob in making the covers?

NG: He let me do my own thing. The first album he let me do was Rastaman Vibration. When I did Natty Dread I went out to England, and I took the images to Island Records. They kind of liked them, but said they weren’t recognisable enough. Because Bob was relatively new. They wanted something more portrait-like. And I hadn’t brought any of the black and white stuff that I ended up using for Rastaman Vibration, Bob in that militant, Che Guevara look. I did something else for Rastaman Vibration, which was Bob with his face in the map of Africa. That was really a new thing at that time. But the design had some similar elements to [Bunny Wailer’s] Blackheart Man, which I had done before Rastaman Vibration – lions and His Majesty and things like that. Chris Blackwell [the boss of Island Records] liked it, but Bob said it was too close to Blackheart Man, so I had two days to come up with a new concept for Chris to take back to England.

I was living at Hope Road – we had a cottage near the main house – and I went down there to ponder about it. I was messing around, and I did a water-colour wash over a photocopy of one of my black and white images of Bob. Canvas was really expensive and I’d been painting on burlap – there was a company in Jamaica making burlap. So I cut the image out and stuck it on burlap and put it on my wall. And lo and behold, Bob was outside my window. I wasn’t aware, but suddenly heard him say, ‘An album cover dat!’ And I look out and Bob says, ‘I like that, I like that.’

After that, if anyone had any input it was Chris. Bob usually left it up to him – he felt Chris knew more about marketing. Once Chris said, ‘Yeah, that was great,’ it was easy for me, I didn’t have to go through the Island Records art department and worry about anyone else approving.

This was the first time a Jamaican act had any type of control of what their album covers looked like. Whatever the record company came up with, that’s what they accepted. So I kind of created myself as the art director, because no band never had nothing like that before. Then I started to do lighting, stage setting, all that stuff – they really didn’t know the value of that at that time. As a result of us, Third World and other groups that came up had their own lighting and people working on their art.

CM: Didn’t you play with the band?

NG: Yeah, the thing with Bob was that he encouraged people around to get involved and I ended up playing percussion, the tambourines, the drums … Being involved in the band gave me a greater insight into what was going on in the music. I never really considered myself a musician, but what I learned made me part of the band and allowed me to go on tour with them.

CM: How political were your covers?

NG: Rastaman Vibration, with the burlap and all, was trying to show the roots of the Rastaman. And I always liked to use gold, green and red, because they’re such brilliant colours, even in a minimal way. For example, on Rastaman Vibration I just put three stripes on Bob’s hat, instead of plastering it all over it. Even if you only use the colours as pen lines, they’ll still come out. I was trying to use the covers to make some sort of social commentary. To get in people’s heads a little bit. I knew it might not save the world, but I wanted to stimulate some kind of thinking.

CM: Did the covers influence other genres?

NG: I didn’t take much notice. It probably came out more in other reggae covers, where people would do similar things.

CM: Where you cool with that?

NG: Yeah, I was cool. That’s the biggest flattery. Where I think using Rasta colours made more impact was in lighting. When I first started lighting Bob, I remember wanting to use Roscoene 874 (I think, I can’t remember the number), which was a real brilliant green, to get the green in the rasta colours. But all the lighting companies were saying, you can’t use green because green is a dead colour. Eventually I saw punk groups and rock groups using the same intense greens that I was using with Bob.

My lighting was untrained. All I was trying to do was reflect what the music was about. Bob’s audience was predominantly young white kids and I didn’t want the message to get lost in the beat. I created a Marcus Garvey [the Jamaican nationalist leader] backdrop, or a Haile Selassie backdrop, I think I was channelling them mentally into what the music was reflecting.

CM: So that was their introduction to the culture, the religion?

NG: Yeah, most times when groups did backdrops it was, like, their logo or something. I was reflecting what the music was really speaking about.

CM: Were there ever any censorship issues?

NG: No, never. Chris always gave me that respect.

CM: And outside Island?

NG: Well, the thing was, once it was okayed by Chris, I never cared what anybody said. As far as I was concerned, reggae was another bag and we were blazing a trail. No one had ever been there before, so no one could direct us. Even my lighting, that wasn’t conventional. Thank God for light boards. There was one I liked, which was like a keyboard, I actually felt like a musician. Being part of the band, I knew all the beats. That whole thing with lighting is anticipation – timing is very important. You can’t come after the beat or before the beat – you have to come on the beat. After a show I’d be as sweaty and exhausted as Bob.

CM: You also designed covers for Peter Tosh, among others. What was it like working with him?

NG: Peter sometimes had more input than Bob. No Nuclear War, for example, that was mainly his concept. He wanted to be standing on two missiles and shooting lighting bolts out of his hand, wearing a gas mask, stuff like that. Bob never interfered in what I wanted to do, and I preferred it that way. But that’s how Peter is.

CM: What were the main materials you used on covers?

NG: Sometimes I’d use illustrations, like in Confrontation. Rastaman Vibration was kind of an illustration. But concept was the most important thing to me, because we were doing concept albums, not compilations. The titles, which I helped Bob pick a lot of the time, were usually one-liners. Kaya. Survival. Confrontation. Uprising. The challenge was to reflect what was in the package. The album cover is the first thing a person would see in a record store. One guy reviewed Exodus, and said he was kind of scared of what the music would be like because the cover was like a Cecil B. De Mille production, with all that gold. Usually when you have a very slick sleeve, the record ain’t no good! Too Hollywood. I would never design something for somebody without first listening to the music.

CM: Did you ever have an assistant?

NG: No, I did everything by myself.

CM: Were you comfortable with photography? Your book was great …

NG: Well, I never considered myself a photographer, I maybe had one class at UCLA on photography. For me, photography was just another tool, like painting, illustration.

When I did the book on Ethiopia, that was the first time I’d shot so many rolls of film in my entire life. I was always very economical – the negatives from Rastaman Vibration are all on one single roll of film. I never had money – if there were 36 frames, I’d try to get the maximum. Whereas a photographer in the US would be rolling off six or seven rolls of film to look for one photograph. It wasn’t till I got to Ethiopia and decided to record my travels, I shot 60, 70 rolls of film in three and a half months. I’d never done that in my life. I also shot video footage of my trip, which I’m still trying to see if I can get money to get it edited to make a documentary.

CM: How much emphasis do you put into technique?

NG: I didn’t really know much about technique. In fact, when we did Songs of Freedom, the Adrian Boot photograph I selected was a black and white photo, and we used Photoshop for one of the very first times and colourised it. It was a picture that Adrian had kind of discarded, but I liked it. He was, like, ‘Oh, well, the lighting wasn’t right, blah, blah, blah.’ And I said, ‘I don’t care about that. I like the mood. I like the composition.’ So we went in and we tweaked it just right. It was always the subject matter that was important to me. It wasn’t the technique. You can be technically great, but if you don’t have vision, then you just have a technically great photograph. That’s not going to inspire nobody.

CM: You’re working on several Marley reissues right now. How is designing a CD cover different than an album sleeve?

NG: The biggest difference is size. A record sleeve is basically 12in by 12in, a little bit bigger. Whereas a CD is half the size, so you can’t do something with a whole bunch of details in it. Like Earth Crisis, which I did for Steel Pulse. I put a lot of things into that – the Ku Klux Klan, the Pope, Vietnam, the IRA, famine in Ethiopia. With half that size, a lot of the information could get lost. The one advantage the CD has is that the record company might do a booklet, where you could put the words of the songs, more images. But I definitely preferred the LP format.

CM: Do you think the inclusion of booklets and such has reduced the importance of covers on CDs?

NG: No, it’s just you have less room to work. Whatever statement you make, it has to be small, but very eye-catching. You can’t go into little tiny details because they’re going to get lost.

CM: How has technology changed things since you started?

NG: When I started I had to hand-letter, had to get things typeset, and if the size wasn’t right, you had to do it over again. Then you had to do the paste up, get rubber cement. It took a longer time.

CM: Were you always in a rush situation?

NG: Most of the time. That’s been the story of my life. They always wanted it yesterday.

CM: Do you have a favourite cover you designed?

NG: Survival and Confrontation. Confrontation was after Bob had passed and no one knew what to call the album. But while he was sick, he had said to me, ‘You must start working on the new album.’ And I said, ‘Don’t worry about that. We’ll talk about that when you are well.’ But he said, ‘I want the album to be called Confrontation. The fight of good against evil.’ So when they decided to release those tracks that he had left, I said, ‘The name of the album is Confrontation.’ I came up with the Ethiopian theme of St George and the Dragon. A lot of people thought that was a British concept, but I found there were twelfth-century frescos of St George at Lalibela [a holy city in Ethiopia] because he was Ethiopia’s patron saint. So I figured representing Bob as St George would be a fitting tribute to him. I spent about 100 hours painting that thing, because I figured that be the last album I’d be doing for Bob.

CM: Talk about the gatefold for Confrontation.

That battle [the battle of Adowa, in which Emperor Melenik’s army defeated the Italian forces] took place in 1896 and there are a lot of Ethiopian depictions of it in their art. So what I did was kind of an adaptation of my research on those paintings. I painted the Italians that way because they tend to put the evil people in a profile view when they paint. When they’re evil you only see one eye.

CM: How big of an influence has Ethiopia been on your work?

NG: Ethiopian art and Ethiopian history is still unknown to the West. I’ve been writing a script called Article 17, which is based on that war. That’s my epic that I want to get made one day. It’s hard to sell, because they look at it as a documentary. But I’ve been writing it as a feature – I start it off as a love story between an Italian girl and an Ethiopian refugee taking a class in international conflict at Villanova University. And I weave the story from there, using flashbacks, back to the war and the life and times of Melenik. I describe it as Jungle Fever meets Braveheart.

CM: Would you like to get more involved in film?

NG: Most definitely. Whatever medium I can reach the people, I apply myself to that. And not many people still read. They want to sit back and have a beer and watch something. So I figure if I’m going to reach people, the cinema screen is the best way I can get my ideas out there.

CM: What happened to the planned film biography of Bob Marley that you were involved in?

NG: That hasn’t materialised yet. I’ll probably end up putting my first movie out when I’m 55. [He was 51 in July.] Hopefully it won’t take that long, but I won’t compromise my concept. To me, if entertainment doesn’t contain information, then I don’t really want anything to do with it.

CM: Can you see yourself returning to album covers?

NG: I did one recently for a rock group called Soul Fly (Primitive). That was a trip. Because when Max Cavalera [the band’s lead singer] contacted me, I said, ‘Oh God, I’ve never done a rock album before.’ And I was kind of confused for six weeks, trying to figure out what to do for a rock cover. And then the guy from the band called me and said, ‘I just want a Neville Garrick cover. Just do what you want.’ So it worked quite nicely.

CM: Have any Jamaican designers followed in your footsteps?

NG: Well, I haven’t really kept track, because I’ve been more into film and music. I don’t really know what’s happening on the reggae scene. As far as I’m concerned, all the songs have been written by Bob already.

First published in Eye no. 41 vol. 11, 2001

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.