Winter 1991

Russell Mills: Material and metaphor

Russell Mills was the original punk illustrator. Now he makes images of delicate abstraction.

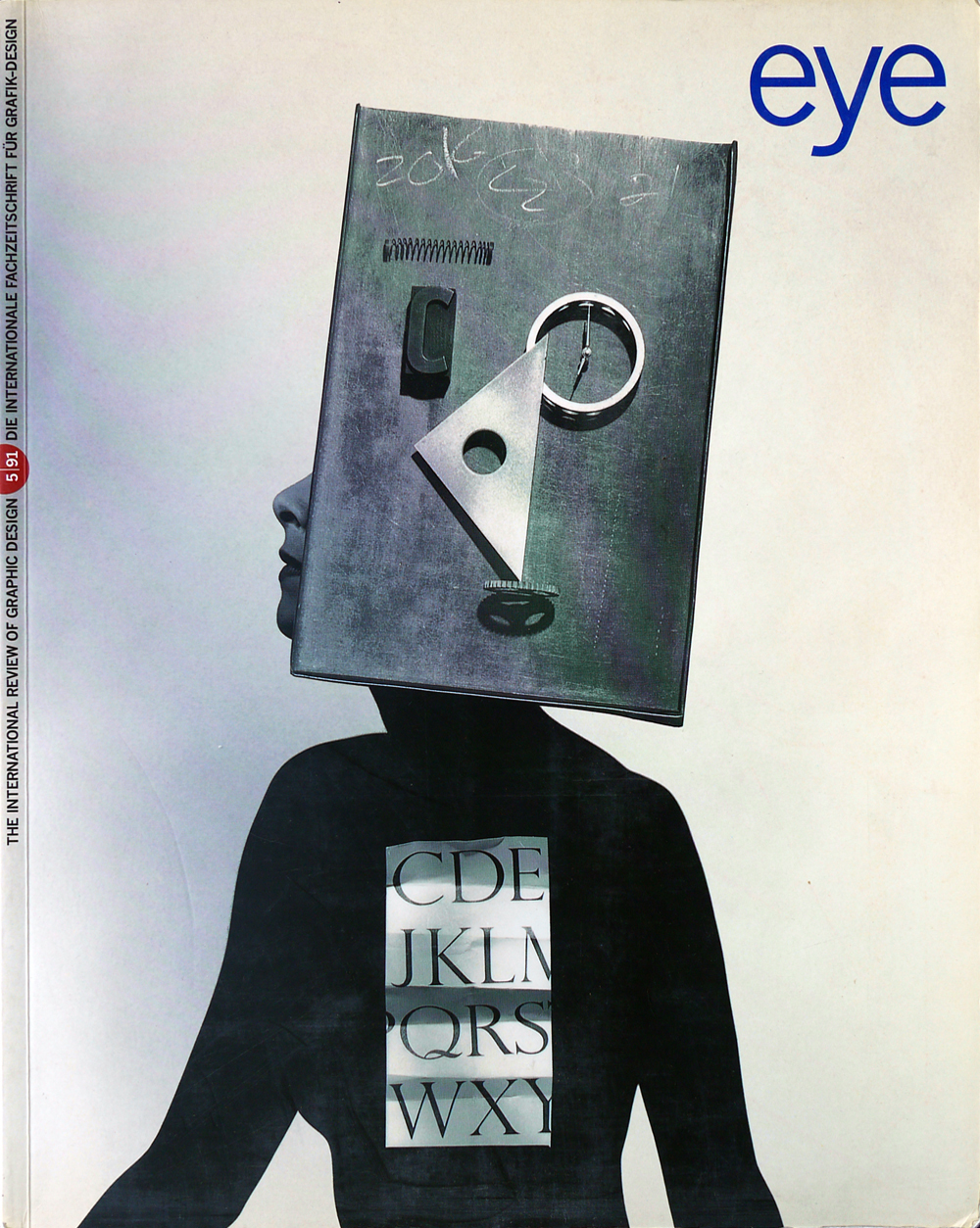

Weathered surfaces and subtle textural effects, allusions to cycles of natural decay, sensitivity of touch and a self-evident display of the material properties of collaged or constructed elements – these are among the most characteristic features of the work of Russell Mills. Among his formative influences, Mills cites the proto-conceptual art of Marcel Duchamp and the Dada and Surrealist collages of Kurt Schwitters and Max Ernst. He also acknowledges direct debts to contemporary artists such as Anselm Kiefer and Antoni Tàpies, two masters at manipulating unconventional materials, and would therefore seem to have an honourable pedigree for a painter working at the tail-end of the century of Modernism. What remains problematic about Mills is that his reliance on such strategies, as well as his idealistic faith in the unique artwork as an agent of intimate communication with the viewer on a one-to-one basis, has occurred largely in the context of illustration, a field often dismissed as tainted by the external demands of commerce.

The view still prevails that both design and illustration, by their very nature, are destined to be no more than adjuncts to the more creative statements within the fiction, poetry or music to which they refer. Conversely, it tends to be seen as a failure for an illustrator or typographer to have too much of a signature style, since it suggests an inability to submerge artistic pretensions into the more pressing need to call attention to the product being sold and to its own particular qualities. Mills has defiantly refused to subscribe to these views, and so thoroughly overcame initial resistance to his unconventional approach a decade or so ago that he has created in his wake a whole school of illustration that bears a closer resemblance to traditions of belle peinture than to the hard sell of the contemporary marketplace. This may not be such a good thing. As Mills himself acknowledges, others have tended to skim off the seductive surface of his designs – with their richly coloured layers beautifully photographed in sharp focus – without bothering to conceive of the images, as he does, as metaphorical carriers of meaning.

Heir to Dada

There is a certain perversity about what Mills does that makes him temperamentally a legitimate heir to his Dadaist heroes. Like Schwitters in his Merz collages, Mills has wrestled a poetry and beauty from the most unpromising circumstances and humble source material. Moreover, he has disregarded hierarchies of importance by steadfastly refusing to recognise any distinction between his ‘private’ and his ‘commercial’ work. It is not only that Mills avails himself of the same processes for both kinds of work, nor that, in his independent paintings as in his illustrations, he remains reliant on literature or music for inspiration. Rejecting the purist mentality that guides both ivory-tower artists and proudly commercial designers, Mills has demonstrated a readiness to make use of a completed painting as the basis for an illustration (sometimes at the client’s request), and conversely has exhibited a picture initially conceived for a commercial commission as an independent work. There is a kind of contrariness, too, in devoting so much attention to qualities of surface and to the integration of images in the form of three-dimensional elements, knowing that the end-product will be experienced almost exclusively in the form of a flat, printed image. In Mills’ view, however, these physical particularities, which might be misconstrued as a concern with illusionism, help to endow the illustration with a mysterious depth. Far from ignoring the circumstances in which the image will be seen, Mills views the photography of his artwork as a critical part of the process, given the ways in which the hand-made surface can be altered through the lens of the camera. He has formed a genuinely collaborative partnership with the photographer David Buckland, with whom he has also designed stage sets and costumes.

There would appear to be an enormous gulf between the illustrations prompted by the early songs of Brian Eno, which brought Mills his first audience in the 1980s, and the much more abstract and elusive designs for book covers and record sleeves for which he is so much in demand today. Although he no longer wishes to work in an explicit figurative style, which he believes restricts the possibilities for individual interpretation, Mills is still attracted by the idea of building a great deal of diversity into his work. He cites the example of Duchamp, who, in grappling with particular problems, devised artefacts so diverse in their outward appearance that they could have been made by different people, yet were clearly all products of a specific mind at work.

Working against his grain

Mills remains to some extent enslaved to his taste and to particular ways of working that suit him, yet there is no doubt that at intervals he has consciously changed direction by reacting against his own habits. The Eno illustrations, for instance, were the product of a series of problems that he set himself as a student at the Royal College of Art in the mid-1970s. In particular, he sought to extend the terms of Dada and Surrealist collage through reference to the disjunctions in this group of contemporary pop songs. Having mastered methods of extremely precise delineation and explicit imagery from ready-made elements, Mills became bored and made a conscious decision to make a change; he was prompted, too, by flippant remarks that his dependence on collage must stem from an inability to draw. Mills embarked on another extended project, inspired this time by his rereading of the shorter pieces of Samuel Beckett, which led him to produce about 80 straightforward drawings of the human head and figure in graphite or white chalk. These came to the attention of the art director of Pan, Gary Day-Ellison, who commissioned from him a series of covers for new paperback editions of Beckett’s longer prose works. Characteristically, rather than adapting the approach of his existing drawings, Mills presented his designs in the form of three-dimensional assemblages, which remain among his most graphically arresting images.

Mills thinks it unlikely that he will ever return to the methods of the Eno illustrations, except perhaps in a fit of pique against those who have continued to mine this eccentric vein of figurative collage, because he thinks a much richer experience is offered through a metaphorical suggestiveness bordering on abstraction. He continues, however, to work from a literal base, feeling an almost moral imperative to key his image into the context of his source rather than merely provide a pleasing design. This need, more than any career consideration, would seem to explain his readiness to continue working as an illustrator and not as a painter pure and simple. In providing a book cover design, Mills rejects the idea of illustrating a particular character or incident, preferring to abstract the essence of its themes, just as he concentrates on conveying the dreamlike mood of Eno’s later ambient music or David Sylvian’s subdued pop records when creating designs for them.

Critical intelligence

In working out a conceptual relationship to the accompanying text, the critical intelligence that Mills applies to book illustrations singles him out as one of the most thoughtful designers in his field. The question remains, of course, about the extent to which his intended audience will be prepared to decipher or decode what at first sight appears to be nothing more than an abstract pattern meant to please the eye. Given that cover designs are often perceived simply as a way of presenting basic information – the name of the author, the title and perhaps a clue to the imagery within – do we now approach such images with sufficient intellectual expectation to allow us to appreciate them? Would we realise, even after reading Zoo Station (let alone beforehand), that the configuration on the cover resembles an abstract map of Berlin bisected by the Wall? (The strings linking the two sides are a visual metaphor for common bonds that were still at work when the city was physically and politically divided.)

For Mills’ illustrations to work consistently, we have to learn to scrutinise them with the same intensity that we would give to a painting in an art gallery. In the fast turnover of the marketplace, this may still be expecting too much, but in illustrating authors such as Beckett, Milan Kundera and Josef Skvorecky, Mills at least has the advantage of knowing that his books will be in the hands of attentive readers. His ambition for illustration, which some no doubt see as misguided, is both honourably traditional and paradoxically radical: to use it not just as decoration but as an agent of interpretation and enlightenment.

Ember Glance: The Permanence of Memory, a compact disc and book documenting an installation in Tokyo by Russell Mills and David Sylvian, is published by Virgin Records.

First published in Eye no. 5 vol. 2, 1991

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.