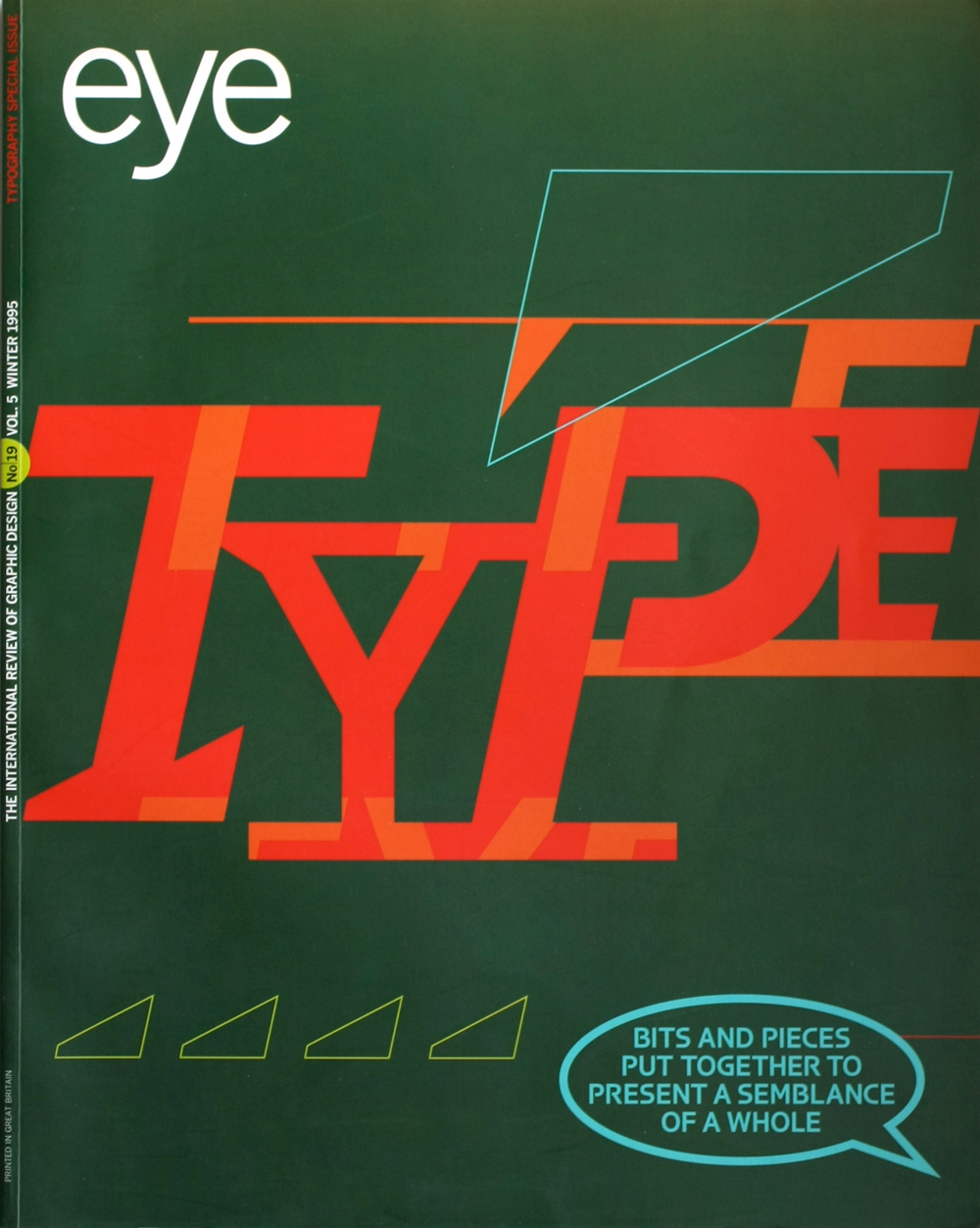

Winter 1995

Signs of trouble

British designer David Crow uses his personal projects to question the authority of the graphic image. By Julia Thrift

‘The trouble is that what I do doesn’t fit into the traditional idea of what a graphic designer produces,’ says David Crow. ‘Graphic designers tend to think it’s not graphic design at all, and say, “Why are you doing it? What’s it for? How are you going to find a home for it that will make money?”’

The part of Crow’s work which is easy to explain is that he lectures in graphic design at Salford University, on the outskirts of Manchester, and that before this he was known for designing record sleeves, the most high-profile of which was the 1991 Flashpoint album for the Rolling Stones. His personally motivated work is harder to pin down. The current project, a study of the semiotics of graffiti, at least has a specific goal in that it is soon to be submitted for assessment for an MA degree. But there is a strong sense in which it is just the latest manifestation of a continuing personal project.

This project is both intriguing and difficult to categorise. What is clear is that its underlying emphasis on designers’ responsibility for the effects of their work and the fact that it is communicating Crow’s own ideas rather than those of a client resonate with themes which are emerging elsewhere in British graphic design. There is a feeling that if graphic design is to move forward, there needs to be a return to an interest in content, in ideals perhaps, in having something to say over and above the messages clients pay to have communicated.

Many of the issues which motivate Crow’s personal work – such as anti-consumerism and the questioning of authority – can be traced back to punk, still a powerful influence when Crow was a student at Manchester Polytechnic in the early 1980s. Crow had arrived there after being brought up in the Scottish border town of Galashiels, which he describes in his soft Scottish accent as ‘pretty, but culturally a bit barren’. For anyone interested in graphic design and music, Manchester was the place to be in the early 1980s. Peter Saville and Malcolm Garrett, who had graduated a few years earlier from the same art department Crow found himself in, were becoming famous for their work for the music industry and the city was buzzing.

Crow found that punk and its aftermath filled gaps in his education. ‘One of the most interesting things about punk was that it introduced me to new reference points,’ he says. ‘I discovered Dada and Surrealism from looking at punk record sleeves. And obviously all those things have a political edge to them.’ A more overtly political influence was the punk graphics of Sex Pistols designer Jamie Reid, which led Crow to an interest in Situationism, the radical 1960s movement which demanded a ‘revolution of everyday life.’ For Crow, the Situationists’ contention that society was being manipulated by capitalism and the media into seeing image – or ‘spectacle’ – as reality was particularly pertinent to Britain during the 1980s design boom.

Crow’s personal work can be traced back to his student days, when he set up an experimental magazine called Fresh which took the form of a collection of separate writings, images and ephemera heat-sealed in a plastic bag. It was enough to get him noticed and led to stints of holiday work with designers such as Neville Brody and Malcolm Garrett. On leaving college he walked straight into a job at Garrett’s Assorted Images, where he designed record sleeves for bands such as Duran Duran.

It was while there that Crow started to publish Trouble, a ‘magazine’ whose format ranged from poster to T-shirt to video. ‘At that time, the mid-1980s, when the design boom was in its heyday, everyone was talking about their turnover,’ he says. ‘The design industry seemed to be overly concerned with commercial gain – I remember seeing the ‘top 100’ design companies listed in Design Week; people were being judged purely in terms of their turnover. I needed somewhere to sound off.’

The first issue, ‘The First Sign of Trouble’, was a screen-printed poster (print-making has long been one of Crow’s interests). It was a visual attack on the way language can be distorted by those in charge of the means of communication, a theme which runs through anarchist political writings and is central to Situationism. Crow mixed his own comments on what was happening in the mid-1980s with snatches of text from Spectacular Times, a series of Situationist-inspired pamphlets. ‘It was about the way we use language,’ he says. ‘For instance, the word ‘revolutionary’ is now applied to everything – even things like washing powder.’

With Trouble, Crow attempted to use the visual language of consumerism – as typified by the record sleeve – to communicate political ideas to a design-aware audience. It could be argued that by doing this he undermined his own message and ensured that Trouble itself would become another small drop in the ‘spectacle’. But for a generation that had grown up reading intensely visual magazines such as The Face, the traditional dour presentation of left-wing ideas looked dreary and out of touch. ‘Spectacular Times used to borrow bits of Situationist text and then add its own things,’ explains Crow. ‘It was quite exciting but it was very badly produced and designed – perhaps that was the point of it – but I felt that it was limiting its audience. Looking at it you would assume it was by a bunch of cranks who could be ignored.’ His solution was to try to make visual form and political content equally attractive.

Crow’s current graffiti project covers issues such as why people feel threatened by graffiti together with questions which are fundamental to graphic design – for instance, why some arrangements of colour and shape are powerfully appealing, while others leave us cold. ‘I have a strong interest in semiotics, the way we see things, the way we read things,’ he says. ‘And I need a place to experiment with that.’ The project is fuelled by Crow’s reading of Roland Barthes and of sociologist Paul Willis, who argues in his book Common Culture (1990) that ‘there is a vibrant symbolic life and symbolic creativity in everyday life, everyday activity and expression – even if it is sometimes invisible, looked down on or spurned’.

Crow’s response to Willis is to side with those designers who believe that the images they create should be ambiguous enough to allow the viewer some freedom of interpretation. A practical example of this is the pictogram typeface he designed for the Fuse ‘Religion’ issue. ‘The fact that something doesn’t communicate a precise meaning could be a strength,’ he says. ‘Sometimes you need to transfer information quickly, but sometimes there’s a leisure element, entertainment. You can stimulate people.’

One of the exercises he engaged in for his MA project was to take a graffiti ‘tag’, change its context and try to discover how this affected people’s perception of it. ‘I found the symbol in Salford, sprayed over things,’ says Crow. ‘It is very similar to the principles which underlie corporate identity: you have this mark, which you reproduce often enough for people to recognise it. I wanted to find out what would happen when you put a designer into the mix. How does the meaning change?’

The result is a ‘corporate identity manual’ – a slick bound volume full of pages of the usual toneless commands about how to use, or not to use, a logo – the difference being that in this case the logo in question is a piece of graffiti stolen from the walls of Salford and slickly redrawn on the Macintosh. The authority of the manual format has been used by Crow to legitimate a symbol which is a statement of raw anti-authority feeling, raising questions about the nature and source of authority in graphic images. The manual is a paradoxical and subversive object: it appears to have the authority of a large company, yet it has none; it appears to have a serious functional use, yet it has no function at all (at least as a corporate identity manual); and it flouts the distinction between fine art and graphic design in that there is no client and no brief for this work, only Crow’s urge to create it.

Asked what he hoped to achieve, Crow came up with a number of tentative answers, the most convincing was: ‘I’m trying to find out how visual artists or designers can make culture more relevant to people who consume it. For years I’ve been designing record sleeves for people who probably make graffiti marks on walls. To treat them like criminals is not even to start thinking about what makes them want to put those marks there in the first place.’

Crow admits that the project is unlikely to result in cut-and-dry answers – if anything, it will lead to more questions. Some might find this too vague, but Crow’s open-mindedness is as important for the way he teaches as it is for his own work. After all, every year our colleges turn out increasing numbers of designers who are highly proficient at creating graphics which make us want to buy things or believe what others want us to. But designers able to create graphics which make us want to question society and the assumptions we hold about it are still in very short supply.

Julia Thrift, design writer, London

First published in Eye no. 19 vol. 5, 1995

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.