Winter 2003

Štorm: living history

The unbearable lightness of being a type designer in Prague

When the Velvet Revolution opened the doors of former Czechoslovakia to visual trends from the West, František Štorm (born 1966) was probably sketching gravestones somewhere in the middle of the flat Bohemian countryside. In 1993 he established his type foundry and instead of experimenting with pixels instantly began to revive the work of the great Czech typographers Oldrich Menhart, Vojtěch Preissig, Rudolf Růžička, Jan Solpera and Josef Týfa. Storm Type Foundry now offers more than 50 font families.

Štorm has an enviably broad knowledge of Czech type history, painstakingly gained through a labour of love. He has learned a great deal from the legends of Czech typography, many of whom he has met, and then developed his own ideas.

For Štorm ‘history is a key to the present and the basis for the future’ as he puts it. Unusual for his generation and his homeland, his work is fuelled by the past. Tradition and history were not important for the Communist regime and since 1989, they do not seem to be important for many contemporary designers.

Štorm still collaborates with renowned type designer Josef Týfa, who is nearly 90: ‘He belongs to the generation of our grandfathers and I love to listen to his memories of other typographers of his time – Oldřich Hlavsa, Jaroslav Benda, or painters like Zdeněk Sklenar, František Tichy and many others,’ he says. Although they are two generations apart, Štorm feels that he and Tyfa speak a common language: ‘The language of letters has not changed very much since the 1930s, when Týfa started his career,’ he says. ‘He is like a teacher to me, and he certainly influenced my own work.’ Their latest font release is the typeface Tyfa Juvenis (2002), to which Týfa returned after a half century break. The pair completely redesigned the font after digitising it: ‘Of course, it wouldn’t be Josef Týfa, if he didn’t redesign the entire alphabet, and to such an extent that all that has remained of the original was practically the name,’ Storm says. Tyfa Juvenis became a contemporary typeface for children’s books.

Another of Storm’s projects was connected to one of the most internationally renowned Czech typographers of the first half of the twentieth century, Vojtěch Preissig. Storm decided to digitalise Preissig’s type himself. He was not satisfied with the solution the US company P-22 came up with – he considers the lines to be ‘too straight’. Štorm obtained Preissig’s original drawings and specimens and consulted experts. Otakar Karlas, a former professor at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design (AAAD) from Prague, and owner of a huge library of Preissig’s original prints, co-authored the new version.

Czech scholar Miloslav Bohatec believes that Preissig used a knife when making letters and that the designs were therefore greatly influenced by the means. Štorm does not agree: ‘The shapes of Preissig’s type come from a certain way of decorative thinking, and I believe that the techniques only served his ideas. Remember that he was also a great freelance artist, he was trained in virtually all known graphic techniques, so he could use any of them for his work. I don’t think the technique was the main influence.’

Preissig has had an indirect influence on many other type designers, particularly in his sense of period, and in his experiments in connecting architecture to design. Though the applications for his typefaces are (in Štorm’s view) limited, Preissig’s work represents an important stage in type development: ‘One can use Preissig’s type merely for monographs or exhibitions of Preissig’s work,’ says Štorm. ‘The forms are so individual that they reduce other potential use.’

Štorm says that he only does ‘what he finds useful’. Discussing contemporary type design in general, he is enthusiastic about small independent type foundries which are ‘ten times more productive than those facing market pressures and employing dozens of programmers and managers.’ He says: ‘Behind each type design we should see a human story of its author – a typeface is not an inanimate object.’ Štorm always tries to explain how the typefaces could and should be used by including witty explanations in the catalogue and on his website, www.stormtype.com. Mramor, he suggests, is ‘not for long texts – sharpness kills & light causes madness’. As for Aichel, ‘the lower-case letters seem to ring with gambolling melodies in their details and behave like immature counterparts of the uppercase letters.’ Some explanations are rich with poetic resonance: Štorm recommends his Walbaum for romantic German novels, because its expression ‘is robust as if it had been seasoned with the spicy smell of the dung of Saxon cows somewhere near Weimar.’

When preparing a new type specimen, Štorm tries to research original prints and specimens:he is well informed about the materials at the Department of Rare Books at the National Library in Prague, as well as at Prague Castle. And he regularly visits the wonderful libraries attached to monasteries around the country.

For an independent foundry all this writing and research means a lot of extra work, but knowledge, and its dissemination, is important to Štorm. Since 2002 he has been head of the typography department at AAAD in Prague where he himself studied from 1985 to 1991.

The department’s programme bears his stamp, based on a balance between traditional and new media. Students’ projects have the freshness and creative energy of an art academy, but they are also interwoven with the rationality and dry precision of an engineer’s approach.

This mixture of creativity and rationality is also present in Štorm’s typefaces. Sometimes he departs far away from the conventions of book-typefaces. Libcziowes, inspired by the vernacular inscriptions on late sixteenth-century gravestones, is one such example, with its awkward, oddly shaped letters. While travelling through the Czech countryside, he became aware that ‘local typefaces were wildly different from Roman-style black letters of Western Europe’. Štorm is a careful observer of this parallel typographic history, full of folklore inscriptions, amateur prints, ephemera and festive layouts made by non-designers; he acknowledges that he loves these elements almost more than the officially renowned type designs.

Štorm’s book typefaces Serapion, Regula and Regent are the result of his interest in the Baroque era. For Štorm the Baroque is a key period: ‘It’s without a doubt the pinnacle of typographic development,’ he says. ‘The label “transitional” doesn’t reflect its importance and may lead to inaccuracy in understanding history.’ In certain details it is possible to see connections with the peculiarities in typefaces such as Libcziowes and Alcoholica. The proportions between the thick and thin and shaping of terminals give texts set in these types a very different structure.

Regula was inspired by a society called Regula Pragensis, which Štorm describes as ‘a group of literates who established a non-religious “monastic order” ’. They have regular meetings with social games; they also run a pub and a library and publish a literary journal illustrated with Štorm’s woodcuts. Štorm now worries that Regula ‘is as overused as Caslon Old Style’.

In 2001 Serapion was used on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine. Storm is not one to get excited about this – he says that a Czech typeface can work well for an American magazine just as American typefaces are used in Czech magazines. ‘I don’t see the nationality of Latin type as that important; it’s firstly a tool for communication.’

Not all of Štorm’s designs have been as successful as Serapion, at least not in his own country. When Štorm designed Biblon for the Czech Biblical Society, the Society rejected it. ‘Custom type design in Prague does not have a good market,’ he explains. ‘The Society wanted very fast and cheap results, and were pushing me to make a font similar to Palatino. In the end I decided to quit the project and I finished the typeface for myself.’ Its basic properties remained unchanged, however: Biblon is a space-saving typeface with eight families, dark in appearance. The typeface won Storm a TDC Certificate of Excellence in the Type Design at the Type Directors Club competition in 2000, and is sold by the International Typeface Corporation as Biblon itc. ‘The collaboration with ITC was interesting,’ Štorm says. ‘They recommended some adjustments to improve the consistency of the family.’ Not that he agrees with all the changes, however; he has also released his own ‘orthodox’ version of the typeface, which he sells as Biblon.

Štorm likes to experiment with historical features used in the notation of different languages. ‘Old features, ligatures and complicated alternates, as well as bizarre new signs for @, &, etc. are the spice of each type design,’ he says. He describes this attitude as ‘a matter of heart’ – one has to be a connoisseur to appreciate it. He adds that in typeface design ‘you have to be as obstinate as a mule if you want to achieve anything really good.’

The peculiarities of the Czech language remain a strong influence on Štorm’s work: ‘There are many diagonals in our language, it is full of “v”s, “y”s and “z”s, there are numerous carons and accents, and it is good to pay attention to these details when you design individual letters,’ he says. ‘Diacritics are an integral part of a design – not merely an afterthought, as many foreign foundries believe.’ Designing diacritics is about responsibility towards one’s craft rather than language proficiency; intuition and familiarity with the language are not key elements in the design process. Štorm is convinced that ‘any foreign designer can learn how diacritical marks should be designed, what kind of shape they should have and where they should be positioned – it is just a few simple rules, no sorcery there!’

Štorm also believes that so-called ‘national typefaces’ such as Antykwa Półtawskiego (in Poland) and Preissig’s Antiqua were merely experiments that did not solve the problem of diacritics. ‘Preissig was wrong, maybe due to his self-importance at that time. His intention, to simplify designing Czech accents, had exactly the opposite result: the accents he added to Monotype Garamond caused a big mess in printing offices in the 1920s. But this is my personal view, I love Preissig for other reasons.’

These days it is difficult to escape people moaning about the invasion of the global economy, the disappearance of regional characteristics and advertising pollution when one visits Prague. But Štorm has more positive views. ‘Things that are really valuable,’ he says, ‘cannot be altered at all. Architectural monuments, thinking and literature are well defended against the ravages of strange anti-cultural influences … Western shit is fortunately easily removable.’ In fact, he would not mind having more cool neon signs everywhere: ‘I can see billboards everywhere, but I’d love tube crafted, moving neon signs, regardless of what was being advertised.’

Štorm’s several memorial tablets are another of his contributions to Prague’s culture. The robust typeface Mediæval – adjusted for the cnc cutting machine – was designed for a UNESCO memorial plaque on the church of St John of Nepomuk and was also used for other memorial tablets. Unfortunately there are not many clients who care enough about the city’s architecture to invite Storm to collaborate in this kind of commission. ‘Type in architecture is my favourite topic. But it’s only because I collaborate with one very good sculptor – who receives all these jobs – that I get involved. Sadly, investors usually don’t see any difference between good and bad types.’

In 1999 Štorm wrote in the magazine Souvislosti that in the Czech Republic, ‘the strongest tendency of the graphic design profession is stupidity’. He explains: ‘My words were directed towards clients, who still do not care and cannot see the difference between good and bad design.’ However, Štorm believes things are changing. ‘I can see that designers and publishers want new, original typefaces. Big type foundries are not as flexible as small companies, or even individuals, who can provide a faster service.And – more importantly – the look of printed and electronic documents becomes more original when Czech typefaces are used. It seems that the times of mediocre minds are fortunately over.’

In the last few years there has been a marked lack of liveliness in contemporary design, due to the impact of the computer, which has forced designers into technical perfection and stiff expression. Although Štorm avoids the defaults of computer-driven technology by drawing on photography, wood-engraving, etching and letterpress printing, he remains optimistic: ‘Technology is changing, but our perception has remained untouched since the fifteenth century.I can survive the lack of irregularities because, to quote Erik Spiekermann, type design “has never been better than today.” I am sentimental and I love old books, but I also remember the period of Linotype setting machines and how designers had to stuff italics and bolds on to the same cap width, how accents had to be pushed willy-nilly down into capital letters … Just imagine the limitations of early photo-setting systems!’ He adds: ‘Computers are human products and therefore imperfection is their basic feature. But they are part of our reality and we should be satisfied with the great possibilities of today’s technology.’

As a matter of fact, the real name of Štorm’s type foundry is Střešovická Písmolijna. So when Štorm went global, he decided to change the name. And, as if he wanted to make a joke about the unreadability of Czech diacritics outside his homeland, Štorm became Storm.

Petra Černe Oven, designer, Reading

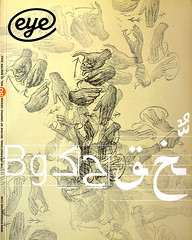

First published in Eye no. 50 vol. 13 2003

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.