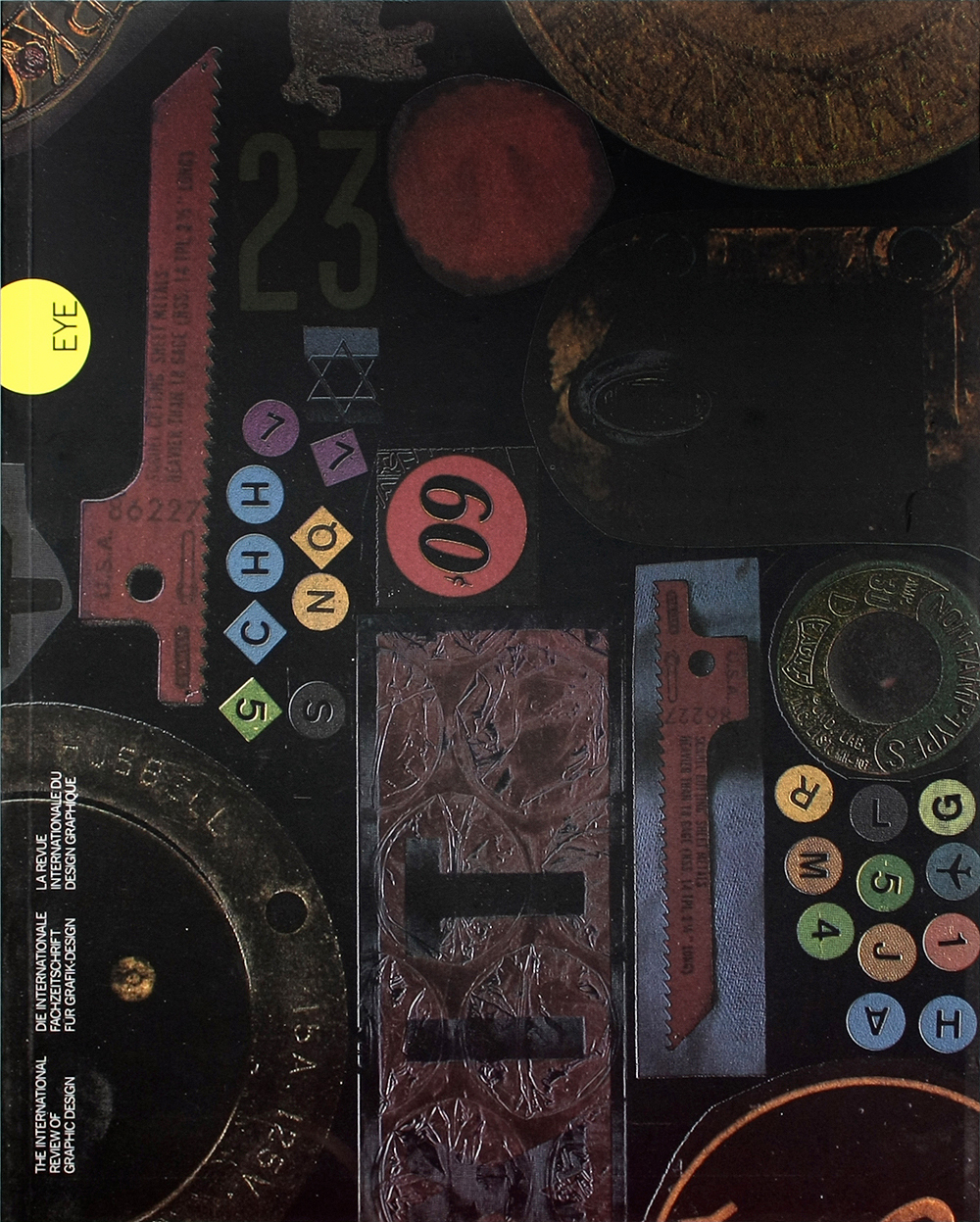

Winter 1990

The designer unmasked

Jan van Toorn has turned graphic agitation into a fine art. Profile by Gerald Forde

In a world in which channels of communication are as clogged with pollution as the environment, the Dutch designer Jan van Toorn is seeking to reverse some of the damage. For 30 years, Van Toorn’s aim has been to rescue the media from its role as a distribution network for dominant ideology, and to reassert what he sees as its legitimate function of communication. Few designers are more clearsighted about the part they play in the transmission of society’s assumptions and values.

‘In my opinion designers are connected to the existing order,’ says Van Toorn. ‘That’s the reality and you have to deal with it. But within that you can still make a choice about your position in the field, depending on your background and ideas, and then if you want you can be a hindrance. And I would like to see many more hindrances.’

Van Toorn’s goal is to contribute to what he calls a ‘counter public sector.’ And as the recently appointed director of Jan Van Eyck Academy in Maastricht – where he is establishing a challenging teaching programme for art, design and theory – he will be well placed to continue the political and aesthetic agitation that has marked his career.

Counter cultural

His first challenge to official culture came in a series of posters and catalogues for exhibitions organised by Jean Leering at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven. Van Toorn saw the museum as a manufacturer of art-media ideology and sought a way of jarring consciousness through visual unorthodoxy. Where Modernist predecessors like Max Bill, Otto Treumann and Josef Müller-Brockmann had been content with the least ornate, most rational typefaces – a level of neutrality that Van Toorn viewed as naïve – he sought out the more idiosyncratic fonts, flaunting the typographic taboos of the then all-pervasive International Style. In Van Toorn’s eyes, the post-war period had witnessed the disciplining of graphic design into a gutless mediator between the interests of international economic and institutional forces, and an audience of passive consumers.

Van Toorn’s interactive programme fitted well with a 1960s radicalism that suggested a world in which everyone might be an artist – a do-it-yourself alternative to the elitism of existing cultural norms. One catalogue required the reader to destroy its binding (and hence his or her property values) in order to access the information. Another, for a Piero Manzoni retrospective in 1969, embraced the kitsch aesthetic with a white fake-fur cover.

Van Toorn’s dismissal of a house style for the museum, and the deliberate informality of much of his work – often using cheap papers and typewritten or hand-rendered texts – could not have been more different from the structural programme operated at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Under the supervision of Wim Crouwel and Total Design, the Stedelijk used a standard grid for all posters and catalogues, giving its products an unmistakable identity no matter how diverse their subjects. Van Toorn’s and Crouwel’s opposing views led to a public debate in November 1972 in which Crouwel argued for a rationalised approach to the packaging of culture, while Van Toorn maintained that this type of uniformity conditioned expectations rather than informing or communicating. This ‘designers’ rodeo’, as it has been called, has assumed a legendary place in the history of Dutch graphic design, but Van Toorn is dismissive of the hype. ‘The best thing we gained is that nobody believes in neutrality any more. But that’s not what the discussion was about.’

Calendar entries

If Van Toorn’s work for the Van Abbemuseum was, as he says, ‘friendly’, then he was to take a far more combative approach in the calendars he designed in the early 1970s for the printer Mart Spruijt. The collaboration had begun in 1960 with Van Toorn still in his ‘classic’ phase, using formal exercises and typographic jokes as an essentially aesthetic programme. But Van Toorn’s work soon developed into what he describes as a ‘laboratory situation’ in which he experimented with images of unprecedented power. ‘I found out in these calendars that it is possible to construct a counter-reality, with more brutality and more openness than I will ever dare do again. That’s the challenge I still have.’

Calendars are by nature ephemeral and Van Toorn’s focus on current affairs means the material has dated, though images such as the bikinied group portrait of Miss Israel, Miss Saudi Arabia, Miss Syria and Miss Egypt, collaged with a photograph of Henry Kissinger, is as relevant a comment on sexism and US imperialism today as it was in 1974. Other pieces are more personal, exploring themes such as the manifestations of identity, self-affirmation and territoriality in Belgian private houses. Another used double images of Holland’s ordered terrain, requiring us, Warhol-style, to look, reflect, compare and look again. Interspersed with quotations from Cage, Lenin, Leonardo, McLuhan, Socrates and Trotsky, the calendars confirmed Van Toorn’s rejection of all that was insular and self-referential in graphic design. ‘It’s a very practical profession and I, by accident, am very much interested in the history of ideas.’

In 1980 Van Toorn began work on seven posters for a series of exhibitions with the generic title ‘Man and Environment’ for the De Beyerd visual arts centre in Breda. In each poster he used a television image of Sophia Loren and her son – a media-age Madonna and child – as an iconic reference point for a complex layering of images. Van Toorn regards the series as the most challenging of his designs: ‘I succeeded, in my opinion for the first time, in arguing with visual means.’ Yet the theoretical intensions underlying these works are not immediately apparent, and one wonders if, without the benefit of a personal explanation, Van Toorn’s designs are significantly different in their final effect from the output of experimental designers with less cerebral concerns.

Academic positions

For Van Toorn the 1980s witnessed a narrowing of the possibilities for challenging work and he favoured instead an increasing involvement in education. During the last decade he has added to his list of academic positions those of head of printmaking, photography, film and video at the State Academy of Fine Arts in Amsterdam and visiting professor at America’s Rhode Island School of Design. He has avoided expanding his two-person operation (his wife takes care of business matters), choosing to continue to work from his home in the north of Amsterdam. His appointment as full-time director of the Jan Van Eyck Academy will certainly reduce his activities as a practising graphic designer.

Today Van Toorn cites only people in other disciplines as having ideas that parallel or supplement his own: Umberto Eco, Jean-Luc Godard, Rainer Werner Fassbinder. This does not mean, however, that he has lost interest in contemporary graphics – on the contrary, he admits to being envious of the professionalism of his colleagues, though he feels that many designers are too concerned with what he calls the ‘gesture’ or ‘performance’ of design to be able to escape the ‘trap of conventions’. ‘Everything is possible, you can quote everything, you can use every style, but where are the arguments that are really contributing to a fundamental change in our social conditions?’

Van Toorn remains the Brecht of graphic design, working on the line between seduction and alienation, constantly finding ways to expose rather than disguise his own role as a manipulator, continually challenging the existing networks of interpretation. On the eve of a new phase in his career, Van Toorn is modest about his achievements. ‘I’m trying to find a solution,’ he says, ‘trying to find the means to say things in a different way.’

First published in Eye no. 2 vol. 1, 1991

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.