Winter 2017

The draughtsman’s characters

Blechman’s Ink Tank made animations that were subtle, literate and humane

In an era of flat, cheap TV cartoons, R. O. Blechman offered the subtlety and humanity of an earlier era – films that were genuinely animated whose library at Washington University in St. Louis holds Blechman’s Ink Tank archive.

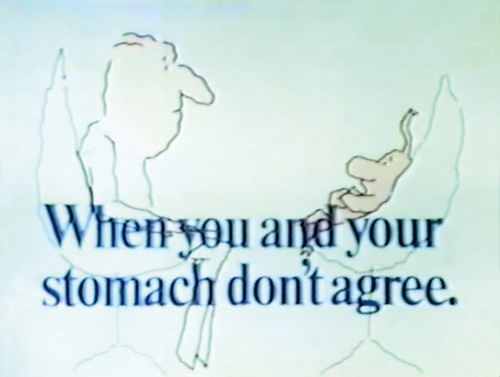

He founded his animation studio The Ink Tank in 1977. At the time, he had worked in animation for more than a decade, having been apprenticed into the field at Storyboard Inc., under the great John Hubley, a co-founder of UPA, a landmark studio of the era. Blechman’s work was introduced to audiences through broadcast bumpers and animated spots. One notable commercial, for Alka-Seltzer (voiced by Gene Wilder at his neurotic best), featured a disgruntled man and his agitated stomach in a therapy session. That ad – a classic – captured Blechman’s gift for persuasive characterisation, incongruously delivered through a broken line that threatened to fall apart any minute.

But Blechman had bigger ambitions. He wanted to direct animated features, to envision sequences and realise scripts at a larger scale. The 1970s had been an uncertain decade for American animation. The era of the well financed animated short (Bugs Bunny, Mickey Mouse) was long gone, and next-wave CGI was in its infancy: Disney’s Tron would debut five years later. Ralph Bakshi’s wayward animated fantasy Wizards was released the year Blechman launched The Ink Tank. Hanna-Barbera was still dominant as a producer of clunky animated television shows.

Blechman’s animation work would be recognised as subtle, literate and humane – everything that most broadcast animation at the time was not.

Among his first major projects as a director was Simple Gifts, a Christmas television special produced for CBS in 1977-78. The programme included six independent story segments, most memorably a charming animated prologue by Maurice Sendak; a telling of the First World War Christmas truce of 1914 by illustrator James McMullan; and Blechman’s own ‘No Room at the Inn’, a wry version of the Nativity.

In 1984 would come his major work The Soldier’s Tale, an animated treatment for PBS of Igor Stravinsky’s music-theatre piece, which won an Emmy award. That film, equal parts folk-tale and corporate allegory, is characterised by imaginative conception, visual richness and savvy pacing.

A proper appreciation of Blechman’s film work would locate him in a draughtsmanly tradition that goes back to Winsor McCay, that pioneer of the field. McCay’s animation work (How a Mosquito Operates, 1912; Gertie the Dinosaur, 1914; The Sinking of the Lusitania, 1918) is dominated by the style and touch of his drawing. Felix the Cat and his goose-necked progeny required no such sophistication, so hordes of in-betweeners could be hired to bang out frames in production. McCay recoiled from the slapstick industrialisation of the field. In his era, Blechman represents McCay-like subtlety and respect for audiences’ intelligence in the production of animated film. His quivering drawings, which seem so slight at first glance, turn out to be supple things indeed.

Right and top: When you and your stomach don’t agree, a 60-second animated spot for Alka-Seltzer, 1967. Drawn and animated by R. O. Blechman. Produced by Jack Tinker & Partners Advertising. A man and his stomach visit a therapist to settle their differences. Voice-over by Gene Wilder.

D. B. Dowd, Professor of Art and American Culture Studies at Washington University, St. Louis

First published in in Eye no. 95 vol. 24, 2018

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 95 looks like at Eye Before You Buy on Vimeo.