Autumn 1990

The good radical

In Eckhard Jung’s work the teaching of Ulm lives on

“Good design is radical,” says Eckhard Jung, the typographer and visual communicator. In Jung’s case, “radical” does not refer to political extremism, but is simply a search for roots, for a common origin for the form and appearance of both living and material objects. Jung, professor of graphic design at the Bremen Academy of Art, examines these roots thoroughly before starting work on a project. In Germany he is known as one of the few responsible practitioners – a designer who does not go in for art for art’s sake, but who anchors graphic design in its social and cultural context.

Jung emerged from the Ulm school. After an apprenticeship as a compositor, his admiration for Swiss typography led him to a job at a Swiss printing works, where he learned about the new Ulm Academy of Design. Between 1963 and 1967 he studied visual communication at Ulm and worked as an assistant to Herbert W. Kapitzki and Abraham A. moles. When the Academy closed he taught at the Düsseldorf Technical Academy and in 1973 found the “design gruppe arbeitswelt” (working world). In 1978 he was appointed to Bremen Academy and the “design gruppe jung” was established.

During Jung’s years at Ulm, the school was searching for a balance between knowledge and form and between theory and practice. At this point in its history, experimental studies in form and projects for industry gained a new importance and ecological themes were addressed for the first time. The seeds of the Ulm approach were not brought to fruition until after the school had closed, though it has since made a decisive contribution to shaping everyday life throughout the world. The narrow, formalistic approach gave way to a philosophical method of enquiry that resulted in work informed by intellectual disquiet and an aesthetic of resistance to consumerism, commercial values and materialism. Jung, too, demands responsible designers. His work is not about fashionable, one-off solutions, but whole programmes for solutions.

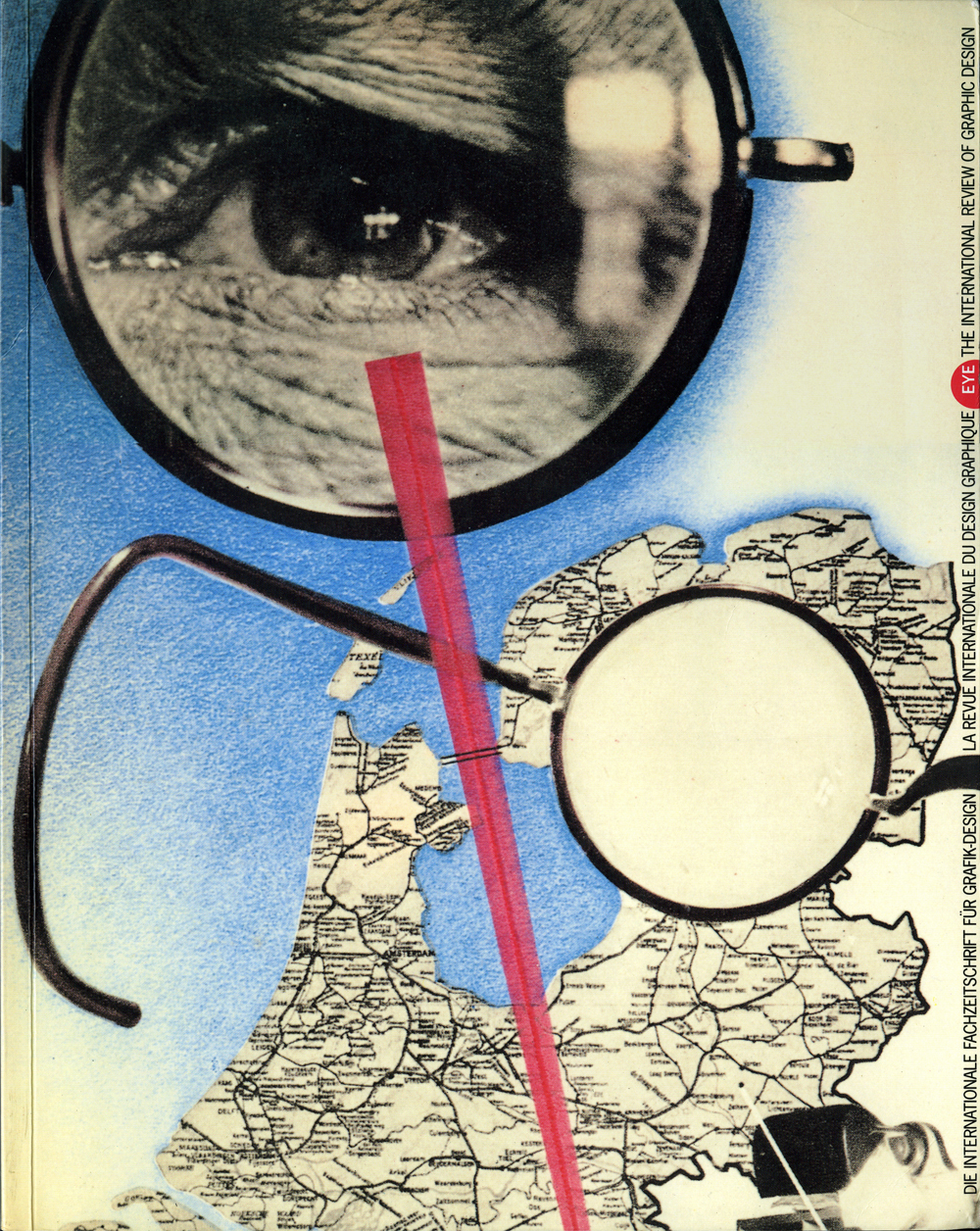

Jung has long since outgrown the strict geometry of the Ulm school. His conceptual design emphasises the humane and is enhanced by an awareness of the sensual” a pictorial language of type and typography. The results make obvious the designer’s subjective and social value judgments and wit; typography is no longer a self-effacing adjunct of the content but allows an enhanced understanding based on feeling. The work of Jung and his students expresses the complexity of contemporary social structures through multilayered, often convoluted designs which stretch the limits of function and legibility.

In the 1970s much of Jung’s work was political, with several projects for trades unions including the “Making Work more Humane” campaign launched by Willy Brandt’s government. Jung’s “I used to be tried after work. Nowadays I am shattered” poster, created in 1982, is a perfect example of his ability to fuse words and images. A similarly challenging message is contained in the triangular book, “So who do you think Picasso is?”, produced by Jung and his students as a record of a week of seminars questioning the contemporary relevance of Picasso’s genius. The format, which pushes the traditional concept of a book to its limits, is stimulating to the senses. It has sufficient sense of order to communicate clearly to the reader while at the same time conveying its messages in emotional terms.

The Bremen Academy has between 160 and 200 graphic design students; Jung works on individual projects with fifteen to twenty students at any one time. He thinks of it as a privilege to work with young people and regards his time with them as a mutually enriching and stimulating experience. Jung’s teaching strategy is based on encouraging his students to think for themselves and inculcating in them a “rebellious” attitude which will allow them to use creative questioning to arrive at responsible and lasting design solutions. Jung teaches visual communication in the broadest sense, offering projects focused on complex themes – signage systems or socio-political topics such as an exhibition on Nicaragua. Projects begin with a discussion of the historical context and current relevance of the theme, followed by a consideration of the problem in conceptual terms. It is not until after this stage that a decision is taken on a particular medium.

Starting with the simple question “What is the problem?”, Jung then takes the students from basic typographical exercises through to free experimental work. The didactic approach of Swiss typography has been incorporated in the teaching method and Jung insists on detailed practical typographical exercises in the manner of Emil Ruder. The students often being by thinking that they are above such elementary routines, but they soon realise their value in developing their critical judgment. There is no more direct way of learning the power of typographical contrast and proportional spacing, the degree to which colours and images alter perception and the excitement of analytical, systematic design.

Although Jung’s teaching is dominated by scissors, ruler and depth scale, desktop publishing has been part of the programme for almost two years. When asked about the effects of the new electronic design tools, Jung has a provocative reply: “There is no need to change design education in any way. People had plenty of scope to produce all kinds of visual rubbish before these Macintoshes appeared; now they can create even more. What is particularly important in the circumstances is more emphasis on visual assessment skills, more training to enable students to visualise language.” This completes the circle back to Ulm.

“The most boring teachers are those who are no longer involved in practice,” observes Jung. This is why he has never given up his own design office. Based in an attic studio in Bremen old town, Jung employs up to three student-designers who collaborate on office projects and develop their own style in the process. For many of them this has proved to be a springboard to their own professional careers.

The design group provides both text and visuals for its projects – an appropriate way of working for a practice for whom the combination of lettering an image is paramount. An example is the campaign developed between 1987 and 1990 to promote the image of the municipality of Stuhr. The previous campaign used the banal slogan “Stuhr ist nicht stur” (Stuhr is not stolid); the emphasis in Jung’s work is on the geographical and cultural features of the municipality.

To date Jung has presided over four generations of students. They are given sufficient space to develop in their own right and to explore their own capabilities. Their work is granted a great deal of public appreciation and many of them have already become teachers or important graphic designers. Eckhard Jung, a revel who has faced up to his social responsibilities, has brought the utopian dreams of Ulm into the present day, developing these ideas further and making them relevant for designers everywhere.

First published in Eye no. 1 vol. 1, 1990

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.