Summer 1998

The Museum of the Ordinary

The exhibits are the entire contents of a swathe of blocks on downtown New York. A proposal and manifesto. By Michael Rock and Susan Sellers

The ‘museum’, the word and the idea, holds a special position in the collective consciousness of the design profession. Inclusion in a permanent collection seems to verify the value of a designed object, since the museum is charged with the eternal protection of significant artefacts and masterworks. The imprimatur of inclusion is a potent marketing device in itself: the tagline ‘included in the collection of the XYZ museum’, promotes everything from wristwatches to laptops. The museum-sanctified design object may be the only masterpiece – albeit a mass-produced one – available to the average consumer. Grafting the concept of permanence to the ephemeral activity of design, the museum provides an institutionalised constancy and inoculates against the anxiety of fashion.

It is against this backdrop of social elevation, high-culture marketing and institutionally sponsored good design that we propose The Museum of the Ordinary (M.O.). The museum is an exhibition space contained within an urban grid but at its heart the M.O. is a Modus Operandi: a method of procedure, a way of working, an engine to generate both theory and practice. In essence, The Museum of the Ordinary is a way of looking.

M.O. is an institution born of institutional apparatus: the business card, the logo, the mug, the press kit, etc. These signs of legitimacy conjure up legitimacy. (Our motto: The cart drives the horse.)

Our primary organisational unit is the name of the museum itself, which frames a range of curatorial activities that are not unified by an architectural container but by thematic and ideological connections. The name is also a perimeter. M.O. also sets out to re-invigorate and to contradict established precedents of conventional design museums. Modelled on Rem Koolhaas’s new urbanism, M.O. rejects what he described as the ‘… twin fantasies of order and omnipotence; it will be the staging of uncertainty; it will no longer be concerned with the arrangement of more or less permanent objects but with the irrigation of territories with potential …’ The museum and the city are one.

M.O. draws on the work of Richard Long and Hamish Fulton, David Wilson’s Museum of Jurassic Technology and Guy Debord’s notion of the intentional drift, the dérive. ‘In a dérive …’ Debord wrote in 1957 ‘… one or more persons during a certain period drop their usual motives for movement and action, their relations, their work and leisure activities, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there.’ M.O. is a directed walk, an informed wandering.

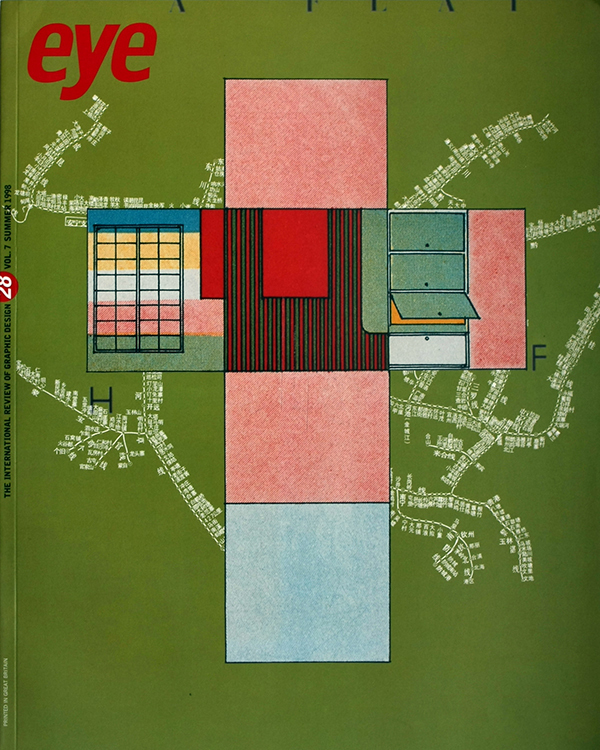

The Museum has a perimeter and a permanent collection. The perimeter is defined by four intersections on the grid of Manhattan. Their co-ordinates are determined by one plate of a standard Sanborn real estate map (Sanborn Map Plate 20/Section 2. Manhattan blocks 472-503). The Museum includes all spaces above, on, and below street level.

The permanent collection consists of all the designed objects within the perimeter of the Museum, therefore the collection is in a constant state of acquisition and divestiture. M.O. is especially concerned with the urban and the physical form of the city as a manifestation of an ongoing, unending process of design.

Since the collection is so large, it is the responsibility of the curators to subdivide it into units that may follow the urban structure – streets, avenues, blocks, buildings, spaces – or inscribe other systems of organisation within the cityscape – all southwest corners, façades, subways, sewer lines, rooftops. The devices for exhibition and publicity are typical of any museum: the label, frame, vitrine, pedestal, gallery plan, projection, cordon, catalogue, window display, guarded installation, newsletter, museum shop, souvenir poster, T-shirt, etc. Exhibitions reflect the curators’ tastes, fascinations, specialities or fetishes. They take the form of street events, performances, pamphlets, books and catalogues. They could be as elaborate as an organised demonstration, or as simple as an individual security guard imbuing some defended object with a temporary value. The result of the Museum activity will be a continuous cataloguing of the space. Over time, the Museum publishing initiative will build a visual library of the city site and the curatorial perspectives will be played out in published form.

The goal of the Museum is to exist. The Museum of the Ordinary is a frame, but for the moment at least it is an empty frame: a theory without a practice. If the design museum is primarily about the control of space and meaning, the Museum of the Ordinary is about the release of that control. If the traditional museum is about order, M.O. embraces cacophony. The real museum loves beauty, we love interest. The design museum extracts design as an autonomous object, M.O. sees design as a practice without exteriority. The project, like the streets, is open to all who choose to wander, or work, within it. Since the Museum is ultimately nothing, it allows us to fill it with everything.

This work proposal is the result of our collaboration with Georgie Stout and our colleagues at 2x4: Katie Andresen, David Israel, Penny Hardy and especially Ole Scheren and Alice Twemlow.

Michael Rock and Susan Sellers, designers, 2x4, New York

First published in Eye no. 28 vol. 7, 1998

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.