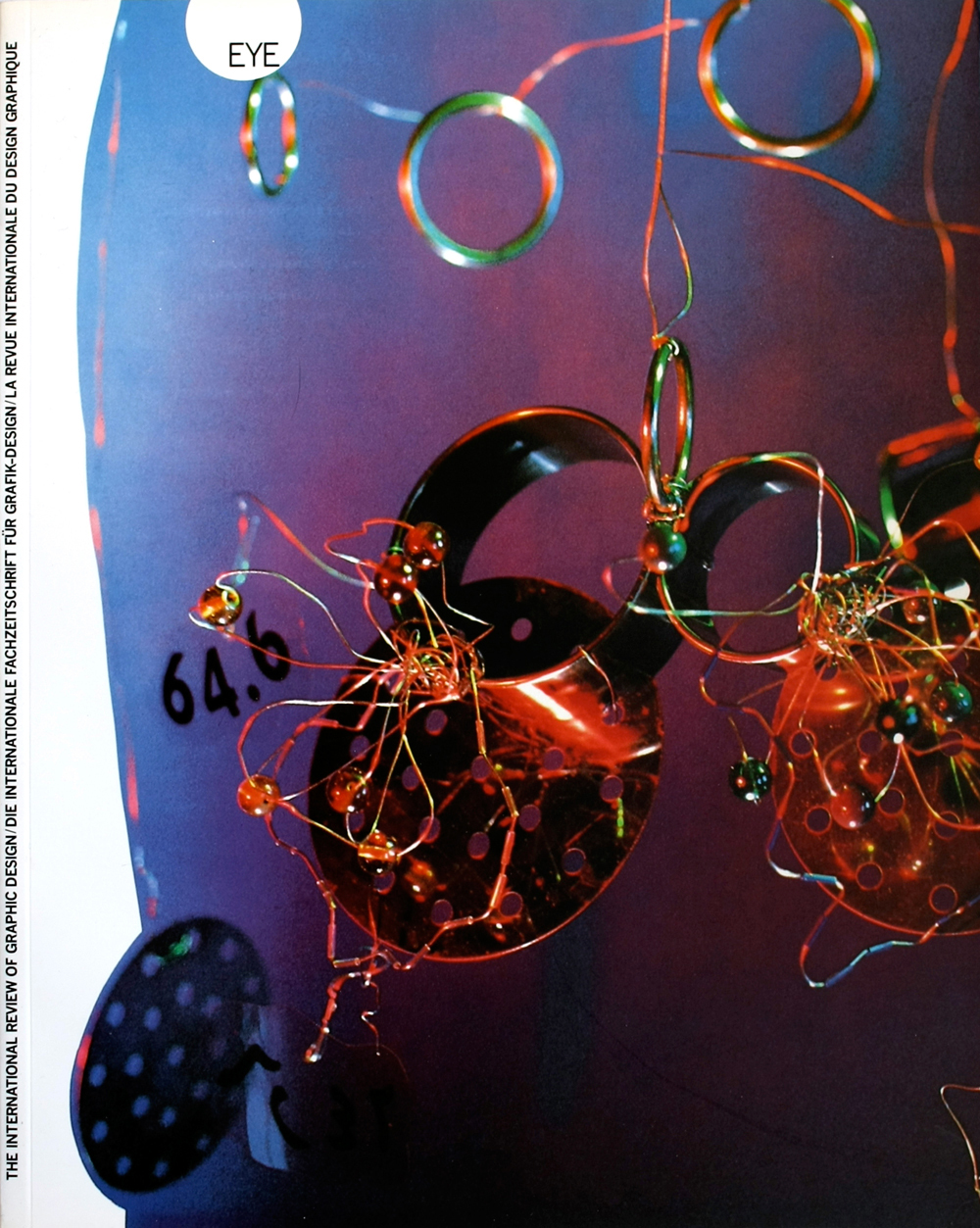

Summer 1991

The Painted Word

While some designers rush for their keyboards, Henryk Tomaszewski prefers to create his posters as he always has — with a paintbrush

It is rare to talk to Henryk Tomaszewski without seeing him take a pencil or pen from his pocket and begin to trace out his thoughts on the nearest available scrap of paper. These scribbles have a vitality that cannot fail to captivate; they tease, provoke, juxtapose and conjure up unexpected connotations. Often there is a pause punctuated by expressions of dissatisfaction. Tomaszewski starts afresh, scribbling as he talks. The scribbles are beautiful, but that is not the point: ideas are in the process of being articulated.

Tomaszewski has never had room for excess baggage. Rhetorical effects or a preoccupation with detail are out of the question; graphic ideas are conveyed with cutting precision. Even as a student, before the war, he focused his attention on the overall unity of a picture, wrestling with form. Tomaszewski‘s first confrontation with his graphics professor at the Warsaw Academy, where he was to become a world-famous teacher, ended in disaster. Asked to pay what he regarded as excessive attention to small details in a figurative composition, Tomaszewski reacted by folding his drawings under his arm and leaving the studio. He spent the rest of his studies in the painting department after only a day in graphic design.

Tomaszewski is one of those rare graphic artists able to combine intellectual agility with a personal handwriting in such a way that the two qualities become totally interdependent. I was reminded of this on seeing the poster for his recent exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, where I talked to my former professor about his work. When Tomaszewski designs a poster he is, in essence, painting a picture. Here, his quick intellect is manifested in a flash of red and black paint set against the cool typography of his own name and the name of the museum. The marks, derived from an old doodle he found in a drawer, spell out the word ‘love’, so that the poster suggests the phrase ‘Tomaszewski loves’. The artist’s sleight of hand makes the letters sing.

For Tomaszewski, the paintbrush remains a key instrument. It is this painterly approach to graphic design which most distinguishes him from colleagues in the West, allowing him, as he puts it, ‘to shine in his disparity’. Even if he were to learn how to operate the new technology (computers, videos and fax machines), he would be unable, he says, to create a new ‘flower’. Yet Tomaszewski’s lightness of touch and purity of colour also differentiate him from Polish graphic artists who otherwise share his approach. Polish posters of the post-war period tended to be baroque in style, dark in appearance and melodramatic in content. Designers were much influenced by Surrealism in its more monstrous forms and, although this repertoire was powerful, it eventually led to stagnation.

Tomaszewski’s un-Polish, almost Czechoslovakian capacity for self-mockery, irony and wit has helped him to avoid this trap. Aware of the dangers of mannerism, he guards himself closely against repetition. He has seen colleagues become imprisoned in a style which then begins to dictate the way in which a picture is made: when style pre-empts content, graphic form is void of meaning.

‘In the simplest of musical forms,’ says Tomaszewski, ‘we can hear a variety of sounds; some are distant, some are close. At various times, these sounds intertwine or become discordant: we are talking about texture. This also applies to painting, where we see soft elements and hard ones. If an artist does not vary the chords, he is doomed to one kind of sound. Whatever the melody, it will always sound the same. Besides, if we are to produce new work, there has to be evidence of an internal struggle. If we are not prepared to destroy an overplayed mannerism, we will be incapable of extracting a new sound.’

To avoid complacency, he explains, graphic artists must learn to practise ‘professional hygiene’. Tomaszewski recommends that designers should create a mental ‘double’, preferably of a different profession or occupation. Looking through the eyes of the double, the designer will be able to see his or her creations more objectively, as if for the first time.

The older Tomaszewski gets — he is now 77 — the more vigorous and inventive his work seems to become. His forms are purer and fresher, the concepts simpler and more direct. Last year, in a Tokyo bookshop, I stumbled upon a magazine containing an article on Tomaszewski. Suddenly I was looking at a body of unfamiliar new work which gripped me by its brilliance of colour and simple dexterity of line. Many of Tomaszewski’s posters and drawings make their point with the same immediacy, particularly the satirical drawings which appeared every week in Warsaw’s cultural publications. Some of the book jackets also derive their impact from the formal interplay of graphic elements, with the artist choreographing coquettish figures and playful letterforms.

Other images are more complex and their wit can only be appreciated with an understanding of their cultural context and the issues they raise. In one theatre poster we see an old coal iron on an ironing board bearing the name ‘Witkacy’. A mental plate on the iron carries the words ‘Teatr Studio’ where we might have expected to find the manufacturer’s name. It is an intriguing arrangement, beautifully drawn, but what does it mean?

‘Witkacy’ was the nickname used by Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz, a famous and controversial Polish dramatist active in the 1920s and 1930s. Teatr Studio was run by Józef Szajna, a prominent figure in contemporary Polish avant-garde theatre who created dramatic spectacles similar to performance art. Whenever he adapted and staged a play by another writer, little of the original author remained. So by adapting Witkiewicz, Szajna is ironing him out, bending and shaping the writer’s work to fit his own vision. It says much for Szajna, though, that it was he who commissioned the poster, while Tomaszewski, without seeing the script or attending the rehearsals, knew exactly what to expect and how to interpret it.

The Stedelijk Museum presented the ideal setting for Tomaszewski’s work. Within the framework of an elegantly organised space, the master’s voice was allowed to echo and resound. A magnificent reception brought together former students, friends and colleagues of all ages from around the world, a moving tribute to Tomaszewski’s long career and penetrating influence. I quietly stole back to the empty gallery for a final look. I was overwhelmed by one emotion — a sense of freedom.

Andrzej Klimowski, head of illustration, Royal College of Art

First published in Eye no. 4 vol. 1 1991

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.