Autumn 1996

The portable art space

Designers who collaborate with artists and curators on catalogues must negotiate a complicated web of interests

For many of us, the printed page will be home to our most frequent encounters with art. But no matter how hard we try to get a sense of the real thing, there will always be a gap between the gallery and the page. Both sites – to use a term from art and architecture – have specific qualities and limitations. The exhibition’s objects are fixed in time and space, whereas the catalogue is a travel-pack of words and pictures. For graphic designers, artists and curators, exploiting the contextual differences may not close the gap, rather it could eliminate the gap completely by collapsing the distinction between art and the reproduction of art.

While the catalogue exists in the service of art and artist, it is primarily an institutional document that is equal parts commemoration, evidence and archive. In its more dutiful capacity, it is a little more than a glorified list. Quiet typography, four-colour plates and a transparent graphic presence attempt to make the catalogue into a paper equivalent of the ‘white cube’ – that utopian notion of the museum or gallery as a neutral container. But such a heavily coded context is anything but value-free.

Context plays a prominent role in the creation and interpretation of works of art. A site-specific piece, if moved elsewhere, ceases to be the same work of art and takes on a different meaning; the specifics of a building’s site predetermine what an architect can create. When a piece takes into account the nature of its intended context – whether art, architecture or graphic design – it can use that context’s cultural connotations and material qualities as an integral part of its message. If the book is seen as a specific site, with all its potential and limitations, then it is possible to imagine the catalogue not as an archive of pale copies but as a distinct and by no means diminished art experience. As creators and manipulators of context, graphic designers are well-qualified to take an active role in re-conceiving the catalogue’s operations in interpreting the meaning of art. But few opportunities to do so exist. The complex workings of the catalogue leave very little room for risk-taking.

‘When you’re dealing with the art audience, you suppose that they’re visually literate,’ says British designer Tony Arefin, who specialised in catalogue work in the early 1990s. ‘But when it comes to the printed format, they’re incredibly conservative.’ All those involved in the process of putting on an exhibition and producing a catalogue have a mutual investment in the value of the artwork that has brought them together, be they artists, curators, lenders, collectors, funders, editors, writers or graphic designers. As a result, printed reproductions are considered sanctified, placing the focus on a faithful recording of the way something looks rather than an experience of its meaning.

There are, nonetheless, projects which subvert, invert, question, critique or otherwise play with our expectations of what the catalogue is and should be. Some are the result of the artist’s initiative; others have grown out of a close collaboration between the graphic designer and the curator, artist or editor. Yet however it is produced, the catalogue sits at the crossroads of institutional, economic and scholarly concerns, and a reconsideration of its role requires that we take into account the range of forces that determine its shape.

A shaper of identity

The catalogue is first and foremost a naming device, a photographic, discursive archive that anchors its subject in the world of art. Biographies, bibliographies and captions delineate that which art history and the art market value most: names, affiliations, origins and ownership. It is, as Dutch critic Hugues Beokraad has written, part of ‘the art machine in full throttle…The institution presents the artist who presents his work. And through the channel of the exhibition and catalogue it inducts the artist and his work into the art world, making them part of a hierarchy and a ritual, of a code and a pattern.’

It is important for artists that catalogues record and substantiate their careers, particularly for younger practioners who are seeking to establish their work in the public record. But they fix only certain aspects of an exhibition, making them history. ‘That moment in the architectural space, that view or that frame in the video, is all anybody remembers of the exhibition. The catalogue freezes that,’ says Laurie Haycock Makela, former design director of the Walker Art Centre in Minneapolis. ‘It’s like your personal photo album. You remember that one birthday party because it’s the only one you have a picture of.’

The catalogue also legitimises the activities of museums, galleries and private collections. ‘It’s a credibility-building thing,’ notes Russell Ferguson, editor at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. ‘The books move around nationally and internationally, they help to raise the profile of the museum in terms of the seriousness of its commitment to programming.’

For curators, a catalogue is the site where they articulate their vision through the arrangement and selection of the visual and verbal elements that are held between the book’s covers. The crucial selection of a writer, or writers, can be an indication of the prominence and theoretical leanings of the curator, the artist and the institution. It is also the curator who negotiates and oversees the level of collaboration that will take place between the artist and the designer.

For graphic designers, whose identity is shaped, in large part, by their client list, affiliation with the art world gives them cultural clout. But it is not an arena for those designers looking to claim territory or authorship. In the exhibition catalogue, identities intermingle in service to the art, and its design and production can be a cumbersome process where the designer has to account for the interests of a dense network that regulates the catalogue’s roles and relationships.

Buying into the real thing

Exhibition catalogues are rarely lucrative endeavours due to their small print runs and high printing costs, but they can represent an investment for an institution or gallery. In the competition for corporate and governmental funding, in both Europe and the United States, art institutions use the catalogue as evidence of their expertise. For smaller galleries, museums and artists’ collectives which are less well known, they operate as printed evidence of seriousness and validity. Currently, as the arts are under attack and funding is scarce, many museums are strengthening and expanding their publications departments in order to legitimise their activities.

Museums used to print only as many books as would walk out their front doors, and this is still the case for the majority of smaller institutions. Catalogues purchases on site act as souvenirs, authenticating the visitor’s experience. But many larger catalogues need to operate independently to reach a more diverse audience, weakening the ties to the exhibition itself. In Britain and the United States, museums and galleries frequently team up with co-publishers, taking advantage of established distribution networks and commercial funding. In this more conventional publishing arrangement, the book’s primary role is as a saleable artefact, rather than an exhibition document, making it an entirely different product to those fully funded, for example, by the Dutch government. While museums try to maintain their autonomy in this tricky negotiation, the co-publisher’s marketing department may get added to the list of those who have a final say.

The catalogue also represents a reproducible, affordable version of the irreproducible and unaffordable, a change to buy into the real thing. But the reproductions within the catalogue will always come up short, no matter how reverential their treatment, and map the distance and difference between art and the reproduction of art. We need to reconsider our notions about what an art experience is, or can be, and attend to the role of context in its formation.

The book-object consumed

As the paper counterpart to the actual exhibition, the catalogue is never actual but always fake, its worth derived only by means of its material relation to its point of origin. The exhibition is unique, time-bound and grounded. It is the original, in the flesh, here and now. The book survives the exhibition, and transcends human time, but no matter how ‘true to the art’, the reproductions within it will always be second-hand and mediated. Like paper money or prayer cards, the printed page is a stand-in for the real thing that we believe to be out there, somewhere. If the catalogue marks a loss, it is the loss of the authenticity of the exhibition.

The catalogue is a visual register in which pictures show that art looks like – as though that is ever any one thing – and in the uniquely Western way, we conflate seeing with possessing and possessing with knowing. We acquire the art in its neatly contained home, locked between the catalogue’s covers, which give the illusion of summation, totality. The art object is subordinated to the book-object, which in turn is consumed by the body.

Yet it is in the object world that the book is the voice of authority. It is the house of words, container of all things serious, distanced and abstract. The catalogue maps the physical and conceptual realms of the exhibition. It is where the work is analysed, described, coded, indexed and recorded – treated to all those activities that books are so good at.

Questioning the frame

Catalogue captions, bibliographies and critical essays find their counterpart in the didactic panels, tour guides and audio programmes that direct our reading of the art exhibition: art and history explained and contained by the institution. Since the arrangement of textual and visual elements on the page and on the wall influences the meaning and stature of the exhibition’s objects, curatorship and graphic design are both interpretative acts. ‘As a designer you’re never credited but always complicit in adding value to words of art, in forming market value and history,’ says Tony Arefin.

Conceptual artists and post-modern critics have long questioned the operations of the institutional frame, from Marcel Duchamp’s readymades to Marcel Broodthaers’ ‘Musée d’Art Moderne’. ‘There seem to be fewer borders between the work and the curating anymore, so that the curator becomes the artist. The artists nowadays want to be the curators as well, they want to have control over their work and influence the context,’ observes Jop van Bennekom, an Amsterdam-based graphic designer whose work blurs the boundaries between designer, artist and curator.

Recently, two Dutch artists have focused their critique on and through the operations of the catalogue. Willem Oorebeek worked with the Dutch graphic designer Felix Janssens to create a document composed of reproductions of reproductions in his book Monolith, between echo & hope published in conjunction with his exhibition ‘Monolith, lettered rock’ at the Witte de With in Rotterdam. The front portion of the book was literally put together from the library of pages that made up his previous catalogues. Thus the layered pages record comments on and participates in the circulation of visual culture, which is an overriding theme in Oorebeek’s work. While a number of the reproduced pieces are in the actual exhibition, the ‘catalogue’ makes no attempt to record the exhibition’s particular moment in time.

In Gerald van der Kapp’s ‘retrospective’ exhibition, ‘Wherever You are on this Planet’, at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, the catalogue is the exhibition. Visitors have to walk through a fabric screen on to which the exhibition catalogue index is projected. The organised by country, city and title, and not by the usual system of chronology and pedigree adopted within the art world. In one room, visitors can assemble their own exhibition from a video projector and a stack of cassettes contain images of Van der Kapp’s art and daily life, past and present. In another, they can sit on one thirty yellow skippy balls, each of which has a copy of the catalogue attached to it. As they leaf through the book, they become a part of the exhibit themselves.

The pages represent an immense image bank in which almost 1,000 reproductions of artwork, party flyers, band photographs, feedback and work by other artists are arranged by subject matter. Every image is exactly the same size, levelling out scale and value. If the reader / participant needs more information, they may refer to the dense matrix of the index. Exploiting the specific qualities of the different media as both art and record, Van der Kaap defies the constraining logic behind the institution’s control of the artist and his work, through the making, arranging and display of the catalogue’s contents.

In cases such as this, the catalogue is used as the vehicle for a larger institutional critique. Museums that support such projects must be aware of their own position within the contemporary critical debates. Increasingly, in Europe and the United States, there is a recognition of the mediating role of curatorial practices and with is a refusal to present works of art and historical artefacts as objects for silent contemplation. As an extension of this, curators have begun to include multiple, sometimes contradictory, points of view in catalogues, along with historical essays and technical information, which as led to a major shift in catalogue contents. ‘You didn’t see multi-authored books ten years ago,’ says Mary DelMonico, head of publications at the Whitney Museum of American Art. ‘Some monographs or books still require single authors, but catalogues more frequently attempt to represent a number of different voices and positions and have begun to include writers from different disciplines.’

This change is consistent with the general trend in cultural criticism where, in the last ten to fifteen years, there has been an increase in critical anthologies and conferences such as the Dia Centre for Art’s Discussions in Contemporary Culture series (co-published with Bay Press), the Culture lab series and the Zone books. Critical discourse has almost eclipsed the work of art as the site where meaning is made; the word – and its proper home, the book – have triumphed. The resulting publications are no longer restricted to the art history section of the bookshop or the library, but may be filed under anthropology, popular culture, or even fiction.

The catalogue for the Whitney exhibition ‘Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art’ is one such book. New York designer Bethany Johns worked closely with ‘Black Male’’s curator Thelma Golden, who wanted to contextualise the exhibition within contemporary cultural discourse. In the catalogue, which contains essays from fourteen different writers, the territories usually reserved for words and picture are re-mapped. The writers, not the artists are listed on the title page and the images of the art are literally treated like a text; their volume and scale make them feel like one essay and – running count tot convention – are present on an equal par with film stills and news footage. Far from being a shadow of the exhibition, the catalogue is a substantial, relevant object in its own right.

The catalogue as site

A number of shifts in art practice, curatorship and criticism have acknowledged the gallery and the page as distinct sites, whether through necessity or choice. The prominence of cultural criticism in the 1980s, the recent cross-over between curators, artists and designers, the rise of theme-based curatorial strategies and developments in installation and performance-based art have all had an impact on what one expects from the catalogue.

When putting together a theme-based group exhibition, the curator assumes an authorial role. By inviting artists and organising words as the exploration of a concept or idea, group exhibitions are generally the outcome of a curator’s vision. Almost by necessity, the catalogue’s cover must be an expression of the show’s thematic content since, in most cases, no single artist should take prominence. Such curators are more likely to recognise the graphic designers operate in a similar capacity, by attending to the presentation of various parts to make a whole. Ever since Pop art discovered the grammar of advertising, artists have exploited the forms of popular media. More recently though, there has been a rising interest in media as site. ‘Most of the artists I work with are very aware of the fact that they can use popular media to get their story out – only in a different form and context,’ confirms Jop van Bennekom.

Importantly, the spatial and temporal presence of installation and performance art resist the single, static eye of the camera and the two dimensions of print, pushing the material qualities of the exhibition and the book even further apart. As the performative aspects of some exhibitions, their ephemeral nature and ties to place have become dominant characteristics, the book has been reinforced as a fixed, reproducible object, making the issue of context impossible to ignore.

Viewing art reproduced on the page may dilute our experience of it, but the aura of the work of art has not disappeared, as Walter Benjamin feared it might. If anything, the ‘fallacy’ of the reproduction has intensified the perceived potency of the original. Perhaps it is time to discard the notions of the ‘original’ and the ‘reproduction’ entirely, and in so doing get closer to the art. By shifting the focus from the object to the idea and its various manifestations, we sever the exhibition’s ties and allow the catalogue to assume its most fitting role, as a site-specific interpretation.

First published in Eye no. 22 vol. 6 1996

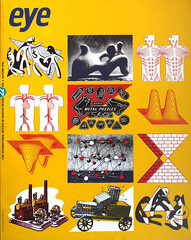

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.