Summer 2014

The retoucher’s accidental art

The reworked press photos now being discarded are unique objects and compellingly strange images. Raynal Pellicer has a collection

One of the most striking exhibitions at Les Rencontres d’Arles photography festival in 2013 occupied a room where the walls were painted a startling Yves Klein blue.

This vibrant backdrop gave more than 100 old black-and-white press photographs an eerie, intensified presence. These were not regular, smooth-surfaced photographic prints. Each picture was covered with reframing marks, blocks of dark paint to eliminate the background, and instructions to the printer daubed in crayon and ink. The aim of this retouching, made decades before Photoshop, was to give the images the maximum impact when printed in a newspaper. Yet each physically modified picture was also a unique aesthetic object, an accidental artwork in its own right, sometimes of considerable power.

The exhibition, titled ‘À Fonds Perdus’ (‘Faded Out’), was organised by the French writer Raynal Pellicer, who has also produced an as yet untranslated book on the subject, Version originale: La photographie de presse retouchée, with Éditions de La Martinière. Pellicer’s background is in television, working for Canal+, France Télévisions, and Arte; he has directed documentaries, short fictional films and commercials. But since 2008, he has concentrated on books about photography. Abrams has published English editions of Mug Shots: An Archive of the Famous, Infamous and Most Wanted (2009) and Photobooth: The Art of the Automatic Portrait (2010). Together, the books constitute a trilogy devoted to highly revealing and expressive forms of non-art photography (though artists exploited the possibilities of the photobooth portrait from its earliest days).

Pellicer’s interest in overlooked photographic genres began when he was making a documentary about the ‘Apache’ criminal underworld in nineteenth-century Paris. During his research he found an anthropometric police photo of the prostitute Amélie Élie, known as ‘Golden Helmet’. The real Élie was nothing like the glamorous figure played by Simone Signoret in the 1952 film of her life. Pellicer set out to investigate the history of the mug shot and question the myth of the cinematic representation of famous gangsters – ‘to give a real face to Bonnie and Clyde, George “Machine Gun” Kelly and Lucky Luciano.’ To pursue the portrayal of identity from the judicial picture to the informal photobooth portrait, and then on to the retouched portrait in the press picture, was a logical step.

The revolver with which Frank ‘The Enforcer’ Nitti, Al Capone’s successor in Chicago, killed himself in 1943.

Top: Humphrey Bogart after retouching. A Columbia Pictures promotional photo by Robert Wallace Coburn for the courtroom drama Knock on Any Door, 1949.

The press photos project has its origins in Pellicer’s mug shot research. In the online archive of the Library of Congress in Washington he found retouched portraits of two Mafia members, crime family boss Charles ‘Lucky’ Luciano and his associate Meyer Lansky. The mug shot is meant to deliver a crude but accurate representation to aid identification. Pellicer concluded that the retouching must have been undertaken for the purpose of publication and, in 2009, turned his attention to old press pictures.

The photos in Version orginale come from American city papers such as the Chicago Tribune, The Detroit News and The Baltimore Sun. ‘Every year, in the United States, dozens of daily newspapers are closing their doors,’ says Pellicer. ‘Others resist, but experience great financial difficulties. If you look at the sums, in most cases, these newspapers and magazines are giving away their archives and original pictures. By tens of thousands! Sometimes for less than $15 per picture. The digitisation and preservation of millions of copies in their archives would cost a fortune. The Chicago Tribune has created a virtual store on the internet and is selling more than 500,000 copies.’

Another source of photos is eBay. If it seems odd that Pellicer’s examples are all American, this is because, as he points out, it is much harder in France to obtain this kind of press photo. Press photographers retain copyright of their pictures, and papers that don’t own the pictures outright are not legally entitled to sell them.

‘By selling their photos,’ says Pellicer, ‘these American papers have revealed to the eyes of the public a hidden or at least unmentionable story. Because, contrary to popular belief, the press photo was not an “untouchable image” or a “faithful representation of reality”. Photo retouching didn’t appear with Photoshop. It was there from the start of photography. From the first appearance of the photo in the daily press, publishers have sought to retouch pictures.’

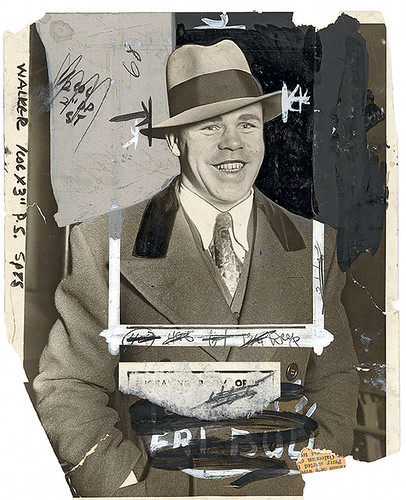

Mickey Walker, world welterweight and then middleweight boxing champion in the 1920s. First published in 1930 by the Chicago Tribune.

The reader won’t notice

In The Commissar Vanishes, photo-historian David King revealed the lengths to which Stalin and the Soviets would go to obliterate political opponents from the photographic record (see Eye no. 17 vol. 5 and no. 48 vol. 12). This was quite different in intention from the retouching shown here, which was mostly carried out for technical reasons, until the 1970s, and applied across the board to Hollywood stars, sporting heroes, Prohibition era hoodlums and ordinary people who stumbled into the news. Newsprint was very yellow then and tended to flatten contrasts, making extra graphic emphasis essential. Pictures often occupied just one or two columns and the removal of distracting background complexities, leaving only the main figure, gave the image more clarity on the page. The retouchers redrew lips, emboldened eyebrows, outlined limbs, gave better definition to the shape of clothing and lengthened the odd necktie when necessary. These visual edits sharpened the pictures. Sometimes unwanted elements of the original were brushed out, such as the head of someone who wasn’t in the story. In a portrait of Humphrey Bogart, the star was unceremoniously stripped of not only his cigarette but also the hand that held it. Outlaw James ‘Big Jim’ Morton’s lack of a jacket and tie presented no obstacle to another retoucher, working in 1925, who simply painted them in with minimal finesse, apparently confident that readers wouldn’t notice a thing when the image was printed small in the daily paper.

Looking at these pictures today at their original size, or as revealing blow-ups in Pellicer’s book, spectacularly defaced (or re-faced) by the retouchers’ marks, alterations that viewers would never have seen take on unintended dimensions. Some become almost spooky. The irises and lids of Morton’s eyes have been boosted with quick, rough strokes so that he seems to stare out with unhinged intensity. In the full picture, the weirdness of his expression is accentuated by the ectoplasmic blobs of pale grey pigment that close in on him like a fungus, and the orange crayon marks clamping his face add to the sensation of mental pressure. The bank robber’s unnaturally framed head seems to be in the process of abandoning his body. At one point Morton was wanted by the police in 39 states and spent much of his life in prison before eventually reforming.

The picture of Evelyn Rice, which appeared in a front-page news story in The Baltimore Sun in 1939, is even more disquieting in its retouched condition and becomes all the more so when one learns of her fate. Rice was murdered by her landlord, who tried to throw investigators off the track by dismembering her body and scattering the pieces around Baltimore in imitation of a serial killer in Cleveland. Little of the original picture, transmitted by Wirephoto, remains intact. Her clothing is now a black shroud, her tragic eyes and lips have been redrawn to enhance their shape, and her airbrushed skin is a ghostly grey mask.

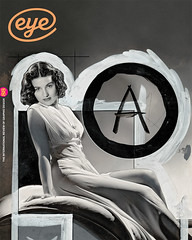

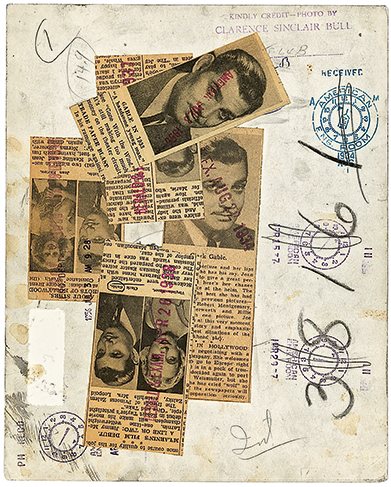

The graphic language of the retouchers’ marks exhibits great variety and, even with Pellicer’s attentive captions, their meaning as instructions is not always clear. In a picture of the actress Brenda Marshall taken by glamour photographer George Hurrell in 1940 to promote the film The Sea Hawk, an artist has painted a black circle, marked by a letter ‘A’. Pellicer suggests that this device is probably meant to indicate the insertion of a second picture, but without locating the printed layout – and in this instance the publisher is unknown – there is no way to be sure exactly what the retoucher intended. Collectively, the marks appear to define an irregularly shaped cut-out, perhaps with an added montage, but here again what the modified photo has become now, a mysterious graphic enclosure in which the star poses enigmatically, has superseded the picture’s obscure and forgotten original use. It’s worth adding that the photos’ backs, smattered with a collage of captions, order numbers, TV transmission dates and cuttings showing how the picture appeared when printed, can in some cases be as interesting to study as the fronts.

Clark Gable photographed by Clarence Sinclair Bull for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1933. The press clippings glued to the retouched photo’s back, which was standard procedure, provide a history of its use by the Chicago Herald Examiner and Chicago American from 1934 to 1956.

Unique works

Almost every piece collected by Pellicer exerts this magnetic fascination as an object to some degree; each has its own distinguishing features. Does he view these photos routinely rebuilt by anonymous craftspeople as part of an everyday industrial process as a kind of art? ‘Unquestionably, they become fully fledged works,’ he says. ‘Not only by being gathered into a collection or exhibited in a gallery, but, above all, because each of these retouched photographs is a unique work. There is only one copy of the retouched photo of Humphrey Bogart with his cigarette erased, unlike the original print. Originally this picture was intended to be just a promotional image for a feature film. But once retouched, and away from its original context, this photo tells a different story.’

Although his research depends on the collections he puts together in the course of each project, Pellicer is not a collector in the normal sense of the word. He doesn’t keep the pictures, but uses them to pay for the next undertaking. ‘I only retain a few original pictures. Selling them is essential.’ He still has the set of 110 photos he assembled for the exhibition in Arles. It needs to be sold in its entirety as a coherent collection because individual pictures are not worth a great deal separately. ‘I like to change the topic of research,’ he adds. ‘I never want to specialise. I love learning about other areas of photographic experimentation.’

Brenda Marshall photographed by George Hurrell to promote The Sea Hawk (1940), directed by Michael Curtiz. Publisher unknown.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, London

First published in Eye no. 88 vol. 22 2014

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 88 looks like at Eye before you buy on Vimeo.