Spring 1995

Think of your ears as eyes

Barbara Wojirsch and Dieter Rehm bring a mysterious beauty to the record label graphics of ECM

Record sleeves have been vehicles for pioneering graphic design since the 1960s, but in recent years the music industry has abandoned its role as a patron of innovation in favour of blandness and conformity. One reason for this is the widespread adoption of sophisticated marketing techniques: where once an intuitive spirit of adventure ruled, now the gods of the high-street and shopping-mall prevail. Second, nearly all recording artists now have a clause in their contract guaranteeing their right to control the look of their graphics. Though in some instances this has led to striking collaborative efforts, more frequently it results in mediocrity and the elevation of whimsy.

It is rarely possible to recognise a record label by its packaging. Among book publishers, an easily identified house style is still seen as a desirable attribute, but the market-driven ethos of the modern record company makes this approach unusual.

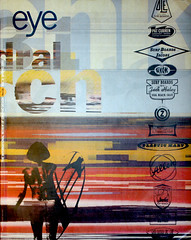

This was not always the case. In the 1950s and 1960s, Reid Miles endowed Alfred Lion’s jazz label Blue Note with a cohesive and confident identity that has become more famous than the music, creating an international style still used by advertising agencies as visual shorthand for hip (see Eye no. I vol. I). More recently, Vaughan Oliver has produced an innovative body of work for Ivo Watts-Russell’s indie label 4AD, and Peter Saville achieved something comparable for Tony Wilson’s Factory Records in the 1980s.

ECM (Editions of Contemporary Music), a small independent label based in Munich, has been in existence for 25 years and under the guidance of founder Manfred Eicher has consistently produced sleeve designs of enigmatic and austere beauty. The label’s packaging exhibits the finest characteristics of the European Modernist tradition: minimalist sans serif typography fused with dream-like black and white photography. Ignoring design trends, the label has maintained a visual identity and stylistic voice that perfectly articulates the distinctive European aesthetic of the music.

ECM is run with visionary zeal by 48-year-old Eicher from a small office above a discount hi-fi store in suburban Munich. A throwback to the days when record companies were owned by record producers, Eicher has himself produced nearly all the 500 recordings in the ECM catalogue. He defies all the rules that supposedly ensure success in the music industry, which he regards as a sort of environmental pollution. Many ECM releases lose money; only a few make a profit: ‘It was never my intention to record artists who had commercial potential, it was simply music that touched me deeply,’ Eicher claims. Among the musicians who have released recordings on ECM are Keith Jarrett, Pat Metheny, Jan Garbarek and contemporary composers Arvo Pärt and Steve Reich. Most are artists ignored by the mainstream who are inspired by the integrity and independence at ECM’s core. Pat Metheny, now signed to major US label Geffen, has said that the only criticism he received from Eicher was that he was being ‘too commercial’.

Eicher has worked with designer Barbara Wojirsch since ECM’s inception. Photographer and designer Dieter Rehm joined them in 1978, and both pay tribute to Eicher’s role in the design process. Enjoying a rare freedom unencumbered by commercial restraints, Eicher, Wojirsch and Rehm have created a body of work which, paradoxically, adheres to the rules of corporate identity and brand management, but is generated by artistic conviction and personal vision rather than commercial priorities.

Eicher denies any conscious effort to create an ECM look. ‘I have never thought of a visual identity for ECM. What I try to express with the people I work with, and what I have tried to express since I was very young, whether in music or visually, is a reflection of my inner state of being. This is very often in a stark and sparse way; a landscape without people… a landscape that is to do with the enigmatic.’

As a producer, Eicher’s recordings have great clarity and lucidity, almost as if the Nordic climate (he records mainly in Oslo) had entered the process. And the packaging too has a clarity, which Eicher defines as ‘a certain kind of personality in our work… something that speaks to you in the image, usually things that are enigmatic, or dry, or weird, dark or cold, images that go well with the music. What I try to achieve is to get people who don’t know the name of the musician to want to find out what the music is like. If this happens then I’m lucky.’

The sympathetic rapport between Eicher and his musicians means that they rarely interfere in the packaging of their recordings. Their views are not ignored, but most are content to let Wojirsch and Rehm work unhindered. There are exceptions: bassist Eberhard Weber insists on using his wife’s neo-primitive paintings on his covers, while Estonian liturgical composer Arvo Pärt persuaded Wojirsch, against her wishes, to create a calligraphic title for his seminal Miserere (1991). But such demands are rare and on the whole Eicher and his team are able to pursue their vision without restriction.

Eicher lists the masters of European cinema – Godard, Bresson, Tarkovsky and Bergman – as having a profound influence on him, and powerful undercurrents of their work can be seen in ECM sleeve designs. He has recently directed his first film, Holozan, based on the novel Man in the Holocene by Max Frisch, with a poster designed by Wojirsch. Many of the photographs used on ECM covers – images of solitude, the sea, desolate landscapes – have a cinematic quality and they are often used sequentially in the manner of movie stills, as in Pat Metheny’s Travels (1983) and Gavin Bryars’ After the Requiem (1991). The symbiotic relationship between film and music is elegantly demonstrated in the packaging for the double CD of Greek composer Eleni Karaindrou’s elegiac music for the films of Theo Angelopoulos (1991), and the extensive accompanying booklet with its many stills.

The influence of artists Jasper Johns and Cy Twombly is also detectable in several ECM sleeves. Garbarek’s Aftenland (1980) uses Johns’ stencil lettering techniques, as does Lester Bowie’s All the Magic (1983). Twombly’s densely textured crayon scribblings provide the inspiration for several of Wojirsch’s covers, including Metheny’s Rejoicing (1983) and the Hilliard Ensemble’s recording of the music of Walter Frye (1993).

Wojirsch trained as a painter but gave it up when she realised that the world was full of good painters. She turned to advertising, but soon became disillusioned: ‘I can’t tell people things that aren’t true.’ When Eicher launched ECM, she found a congenial creative environment, though unlike Rehm, she remains freelance. Her work is characterised by exquisitely stark, minimalist typography based on a small repertoire of sans serif typefaces – what she unpretentiously calls her ‘careful use of lettering’. She positions photographs with the confidence of a designer not striving for effect through fashionable part-bleeds or random groupings of images: ‘It’s a picture, we choose the picture to show it, not because we want to work with it.’ Occasionally she abandons her formal type for a more painterly approach, as in her watercolour lettering for the Dave Holland Quartet album Extensions (1990). A third strand to her work is her use of hieroglyphic and runic symbols – primitive, scratchy images that impart an atavistic quality, as in Garbarek’s I Took up the Runes (1990), Jarrett’s The Cure (1991) and Anouar Brahem’s Conte de l’incroyable amour (1992).

Wojirsch relishes the freedom the record cover allows; supermarket packaging and annual reports hold no attraction for her. She has little interest in computers, eschewing new digital fonts, and restricts her use of technology to the fax machine. Like many sleeve designers, she is saddened by the disappearance of the vinyl LP cover, a format that allowed her to exploit the tactile properties of board, ink and varnish at workable dimensions.

In fact, ECM sleeves have made the transition to the CD format more successfully than most: what Rehm describes as ‘the reduced visual language’ of the company’s packaging translates well into the smaller size. In the 1980s, when record companies converted their back-catalogues to CD, it was rarely done well. Labels such as Blue Note and Impulse suffered disastrously as sleeves printed on thick card with vivid ink and varnish were crudely reduced and badly printed on cheap art paper. For Eicher, the disappearance of the twelve-inch sleeve has implications beyond design: ‘LP covers sent a better signal and there was a sensual side to them – holding a record cover in your hand was like holding a book. Now, with the absence of interesting materials, of dust, the mystery has gone. So too with the music – digital recording has made the sound more neutral. It means there is a mainstream of rather good sounds but we don’t hear things at the edges.’

Today, ECM no longer issues recordings on vinyl and some of Wojirsch’s best work is found in CD booklets, where she creates drama and tension by the dynamic use of white space and blocks of asymmetrical type, as in her designs for the recent recordings of Jan Garbarek. She readily acknowledges the influence of Jan Tschichold and strives for what she describes as a ‘purity’ in her typography.

Dieter Rehm joined ECM straight from art school, where he trained as a photographer, His first contact with the company was when he showed Wojirsch a photograph of a blue sky with a distant vapour trail – an archetypal ECM image used on a 1978 Azimuth recording – and has been part of the family ever since. Like Eicher and Wojirsch, he derives inspiration from painting; otherwise he confesses to a brief infatuation during the 1970s with the work of Hipgnosis. He recognises that record sleeves offer a freedom other areas of design would deny him and sees the process as threefold: ‘You have a picture, which is a cut-out piece of the world, then you have a title which may have many associations, and thirdly you have the music.’

Rehm uses the Macintosh to help with typography, but without any great enthusiasm; his main interest is photography. He works with a small group of photographers who assist in his search for images that express the recurring ECM themes of solitude and beauty: the Hungarian Gabor Attalai and the Swiss Christian Vogt are ECM regulars; Eicher praises the black and white work of Jim Bengston. In recent years a more naturalistic tone has entered the photography, with less use of the cinematic drama exemplified by the Gary Peacock album Guamba (1987).

ECM packaging has its critics: the champions of the new brutalism in music and graphics claim to find it anodyne, a flight from reality. Others praise the fundamental honesty of expression and independence of vision that ECM has pursued for 25 years. The best ECM covers have a presence that justifies their claim to greatness.. Through images that lead to introspection and what Eicher calls ‘the inner landscape’, they bypass the lingua franca of hype and speak in the language of psychological archetypes. There are also many ECM imitators, but like fake Rolex watches sold on street corners, they are easy to spot.

Adrian Shaughnessy, graphic designer, London

First published in Eye no. 16 vol. 4, 1995