Autumn 2005

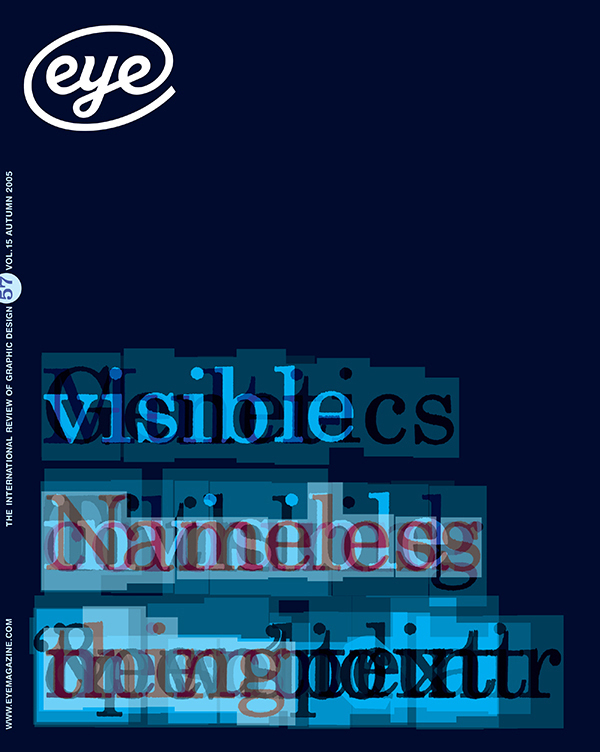

Thinking in solid air

Design educators are finding that letterpress nurtures creativity and visual abstraction. By Steve Rigley

Like many design students educated in the mid-1980s I suffer a form of typo-identity crisis, a slight feeling of deficiency or fraud. It is probably something to do with arriving too late for letterpress and too early for the Mac.

Within our graphics department final year students had priority on the photosetter, a large and clumsy lump that hummed and spewed out bromides to command. For the first two years, all our projects had to be hand-rendered on to a layout pad, which led to many early morning scrambles for a studio lightbox. As full photocopy-card-carrying students we had depth scales with us at all times and kept our Rotring pens clean. We assumed that all that squinting was doing us good, like some sort of visual detox or optical boot camp.

The lead type – or what remained of the university’s facility – had been squeezed into a small, rarely visited room in another building. Unlike my peers I did venture in once and allowed the technician to demonstrate how to set up a forme. But I ‘pied’ it while he was on his tea break and fled for the familiarity of the lightbox. I regret I never got any further than that. The lead type, the photosetter and the lightbox are of course long gone, replaced by successive squadrons of plastic monitors.

Material awareness

For those working in design education this will be a familiar story and quite understandable. From an institutional point of view the cost of maintaining letterpress may outweigh any initial and measurable benefit. A letterpress facility requires space (money), maintenance (money) and a watchful eye (money). Large groups of students will need tight timetabling if they are to get a reasonable introduction (money). And, of course, the managers will cite those academics who consider it obsolete, antiquated or folksy: the preserve of ‘fine printing’, and craft fairs. For students up to speed in Quark or InDesign, hand-setting type can seem painfully slow and laborious. Once printed, the results can be meagre and frustrating; dirty fingernails and a bin full of scraps can be a poor return for a day of standing. Even worse, for those academics who dare venture in for a few hours of honest research, a casual flirtation with lead can remind one how easy it is to romanticise the things of which we have little experience.

In design schools, a few letterpress facilities have survived the cull but are coming under increasing pressure to justify their existence per square metre. Their cause is not helped by the fact that letterpress can at times appear to be caught in a romantic time warp, locked up in the chattering of decorative borders, wood type and poetry. By comparison, successive generations of Mac-literate design students have stretched and redefined the typographic terrain through engaging with the opportunities provided by the same technology they will use in industry. So it would seem that most institutions were justified in their decision to melt down and move on.

However despite the financial and spatial savings and the initial enthusiasm for new digital possibilities there has been a downside. For many students who find themselves hot-desking on crowded courses, design is something to be done in the school’s computer suite (or more likely at home) and then printed out for a crit or presentation. There is no denying the benefit that the Macintosh has brought to typographic practice through opportunities for increased precision and refinement. In fact the most grateful recipients appear to be those trained in letterpress. Unfortunately, for those students unaware of, or unable to access other ways of working, it can prove counterproductive, as the creative process defaults to something more akin to Tomb Raider, singularly dependent upon a computer and a prior knowledge of shortcuts and cheats. At times it can appear that the sheer number of opportunities afforded by the various filters and behaviours is inversely proportional to the quality of the output. Most noticeably, the effect has been to dumb down the physical act of design (even if for some of us this was realised through carrying paper over to a lightbox). As Jean-François Porchez (see Eye no. 45 vol. 12) recently noted, ‘Today students are sat in front of computers all day, they have lost their ability to play with their hands; they are not just for adding ink to their inkjet printers!’

While one could argue that typography has always relied heavily upon technical knowledge – whether it be when hand-composing type or keying into an image-setter – there has always been the need for other skills, most notably the visualisation of ideas through drawing. Yet, as we all know, these physical activities are no longer necessary to answer most student design briefs. In their place, the computer presents a new and artificial arrangement of distances: between the hand and the eye; the screen and the object; the object and the means of production. As a consequence, tutors working on print projects often find themselves peering though crowded desktops, zooming between the palettes and dialogue boxes only to suggest that the student print the piece out to enable a ‘a proper look’ (albeit mediated through the limitations of inkjet paper, printer size, condition of the cartridges, etc.) This ‘proper look’ implies the opportunity to handle, to judge under differing light, to move around and fold, to mark, cut up and reconfigure. Unfortunately these important reflective aspects of the design process, so useful in building spatial and material awareness, can prove practically impossible in a crowded computer suite and appear pointless to many students who consider ‘design’ to be synonymous with moving the mouse.

All that is solid …

Yet over recent years ominous cracks have opened up right across the digital monoscape, driven to a large extent by a strong revival in drawing and customisation. A journey through current design periodicals proves the difficulty of avoiding anything that has not been painted, scrawled, etched or stitched. Not surprisingly, letterpress with its craft associations, finds a welcome space within this new arrangement and has been widely celebrated in recent publishing, most notably in David Jury’s excellent Letterpress: the Allure of the Handmade. This shift indicates that a generation raised on PlayStation and Pagemonkey are now looking for something else – a heightened experience of making perhaps. Not surprisingly, those schools that managed to keep letterpress are now seeing an ever-broadening range of students reap the benefits. Vicky Squire, who teaches at the University of Plymouth, notes an increasing interest among illustrators, artists and printmakers keen to engage with an aesthetic traditionally associated with typography. At the University of Oregon, senior instructor Megan O’Connell encourages student mobility: ‘We move seamlessly back and forth between a wide range of media and methods: from printmaking to photography, from xerography to rubber-stamping, from antique magnesium dyes to custom photopolymer plates. This is a tonic for students who find themselves spending most of their time thinking in pixels and RGB and not trusting the abilities of their own hands.’

Not surprisingly, as these students graduate the enthusiasm permeates out into the design industry. London-based designers Sophie Thomas and Kristine Matthews made a conscious effort to continue a passion fostered while studying at the RCA. On setting up their company they bought a proofing press through eBay which now sits alongside the computers in the Thomas Matthews studio. While Thomas concedes there is a certain ‘decadence’ in owning a press, they have put it to good use. Their recent CrackOut campaign for the Lambeth and Metropolitan Police in London uses bold wood typesetting for the campaign identity, and while the inconsistent inking and crude composition may not be to every printer’s liking there is something refreshing in their use of recycled paper and vegetable-based inks for all print material. Matthews considers letterpress to be essential in the teaching of typography: ‘The problem is that default settings on the Mac stop students from really looking and making genuine design decisions. The actual restrictions of letterpress can be really liberating.’

The manner in which these restrictions build and encourage creativity is carefully examined in the ‘Codex’ research project carried out at Central Saint Martins by Susanna Edwards, Julia Lockheart and Maziar Raein. The project, which questioned how the introduction of the computer in the 1980s has affected the teaching of graphic design highlighted the role craft-based media, in particular letterpress, have to play in design education by nurturing creativity. [See TypoGraphic no. 60, 2003.] Their report reveals how the demands placed upon the student increase their capacity to hold an image in the imagination and to visualise an outcome. A typical example would be how the student will be forced to ‘abstract pictorial space’ when having to set type upside down. While conceding letterpress to be a technology of the past, the project concluded that ‘its intrinsic qualities are of direct relevance to the teaching of computer-aided design … we have realised that through the teaching of older technologies we are able to challenge students to be more questioning about the use of new technologies.’ The findings would suggest that despite the revival of letterpress in ‘the industry’, the greatest benefit well may be to education, acting as a counter or foil to the speed and expanse of digital possibilities. Such sentiments will hardly be welcomed within those institutions that have chosen to invest solely in digital facilities and the golden promise of e-learning environments, but they also offer a timely reminder of how modernism needs to maintain a connection to the past to remain truly modern. As Marshall Berman suggests, ‘If Modernism ever managed to throw off its scraps and tatters and uneasy joints that bind it to the past it would lose all its weight and depth, and the maelstrom of modern life would carry it helplessly away.’ (All That Is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity.)

Farting shrieks and Victoriana

But if is it to be truly modern perhaps letterpress itself needs to move on. Despite an ever-increasing popularity and presence within the design press, the actual work featured can sometimes feel disappointing and predictable. While working within restrictions has clear benefits in an educational context, the limited materials available can sometimes carry just too much historical baggage, and as a consequence the designer can appear trapped within a bright world of farting exclamation marks and Victoriana. Equally while much of the work emanating from the ‘fine press’ community may aspire to a position ‘outside of time’ the movement itself seems deeply caught up in a variety of beautifully delivered period dramas. However, within the hands of a new generation of designers, Mac-literate and less concerned with division or specialism, there is evidently the opportunity for the letterpress revival to be accompanied by new and exciting expressions, for it to be – as Robin Kinross described the works of the Kelmscott Press under William Morris – ‘backward-looking and forward-looking in one moment’ (Modern Typography: An Essay in Critical History). But for this to happen there needs to be a more fluid exchange between the two independent technologies.

Oddly enough, a solution may be found within the fine press world, where many printers have abandoned working purely with lead to achieve greater typographic refinement through the use of photopolymer plates. This simple, affordable process seemingly offers the best of both worlds as computer-generated type is output to film and exposed via UV light on to photopolymer plates ready to be printed in conventional manner. One designer who has already exploited the potential is Stephen Byram in his covers for Screwgun records (see Eye no. 42 vol. 11) printed by John Upchurch at the Fireproof Press in Chicago.

The leading spokesman for this process is the Californian printer and typographer Gerald Lange. His seminal Printing Digital Type on the Hand-operated Cylinder Press (Bieler Press, 2004), now in its third edition, offers the benefit of his extensive interrogation of the process. Lange teaches at Art Center College of Design in Pasadena alongside Gloria Kondrup, professor in graphic design and director of the school’s own Archetype Press which boasts more than 2500 drawers of rare American and European cases of type. The School, and the many others like it which have fought to retain those ‘uneasy joints, scraps and tatters’ and which actively encourage students to study in both foundry and digital environments prove that to be ‘backward-looking and forward-looking in one moment’ is to be truly Modern and genuinely exciting.

Steve Rigley, designer, educator, Glasgow

First published in Eye no. 57 vol. 15.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue.