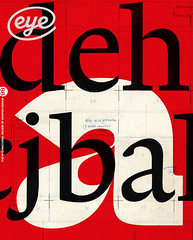

Spring 2019

Two cheers for publishing

A two-volume book packed with graphic design history is a visual blockbuster, but does little for scholarship. By Rick Poynor

Taschen’s The History of Graphic Design, in two volumes, is without doubt the most visually ambitious publication of its kind. It is another of those ‘sumo’-grade productions that the German publisher has made its own. Designer Jens Müller’s project runs to nearly 900 protein-pumped pages and packs in around 6000 images, covering 1890 to last year. It is a stunning advertisement for the subject: what an amazing discipline and calling graphic design has been. The picture researchers – strangely unacknowledged in the credits – deserve some equally outsized gold medals for their remarkable labours. Almost everything you might expect to see is in these two volumes somewhere, along with exciting quantities of much less familiar work.

Cover of The History of Graphic Design, Volume One. Book design by Jens Müller / optik.

Top. Spread of well known posters designed by Paula Scher for The Public Theatre in New York, 1990s.

And yet, one has to ask, are these two monuments really what we need at this point in the stop-start evolution of graphic design history as a field of study? Organised by decade and year, the volumes have the bare minimum of text. Each book has a brief introduction and thereafter the featured designers and themes, all allotted a spread, receive summary paragraphs and biographies of around 100 words, in English, German and French, putting even more pressure on space. These are coffee-table books par excellence and they are designed to blow away the competition, to suck the air out of the room. Why buy Meggs or Eskilson or Drucker and McVarish for a teenager wondering about studying graphic design at university, or for the design studio library, or for your personal viewing pleasure, when these far more extensively illustrated round-ups look like greater fun to flip through?

Taschen’s leviathans seem to want to have it both ways. There is nothing wrong with picture books that serve an introductory purpose, but the extreme weightiness and definitive air of this pair of surveys, and their claim in loud cover type to be the history of the practice, gives them an appearance of serious intent, at least initially. Then, by skimping on the text, they implicitly convey the impression that detailed discussion of design’s contexts and purposes, founded on scholarly research, is simply not necessary for an appreciation of the subject’s history.

Graphic design history is the focus of recurrent bouts of reassessment and I have sometimes taken part in these discussions from the perspective of an interested observer and periodic writer of design history. From its earliest days, Eye has given space to articles about historical subjects and Eye, along with magazines such as Print (now closed down) and Baseline (less frequent these days), provided the most regular forums for publishing graphic design history written for the non-specialist reader. Since I began teaching at the University of Reading in 2016, graphic design history has become even more central to my concerns. I lecture on the subject to first-year students, convene a second-year module that includes history, and recommend design books to the university library.

Those who want to build graphic design history as a solid, cogent and academically recognised area of study have always faced two intertwined questions: who is this inquiry for and what purpose does it serve? While many who work within graphic design might wish the practice could be a topic of wider public concern (like art or films) that is discussed in mainstream media, this happens only fleetingly, if at all, and graphic communication never becomes firmly rooted as a subject people follow and want to read about. After an initial burst of missionary optimism and then watching the discipline for many years, I no longer expect this to happen through popular channels. I have, in any case, always argued that wider interest could only come about if graphic design was first established consistently and on multiple levels as a field of inquiry that could develop and sustain ambitious writing within its own disciplinary borders, including the writing of history.

This brings us to the core audience for graphic design writing: graphic designers. Graphic design history has no independent, departmental home within universities. It is taught, as I teach it myself, within wider graphic design programmes to students who mostly intend to become graphic designers. The people who read graphic design publications and buy graphic design books are mainly graphic designers and this is the same everywhere. In Graphic Design: History and Practice (BU Press, 2016), a collection of texts based on a conference, Italian design researcher Carlo Vinti notes that until the 1990s graphic design history was not taught at all in Italian universities. ‘As for today,’ he writes, ‘the demand for an education in this subject still comes from within the professional design community itself. Moreover, design students are not just the broadest and most accessible audience for design historians dealing with graphic design, they are also the people who will probably be the most interested in engaging with historical research and study on the subject.’

Cover of The History of Graphic Design, Volume Two. Book design by Jens Müller / optik.

An issue of funding

Publishers are all too aware of the highly circumscribed nature of the market for graphic design history books and it makes them extremely cautious. Who will buy a serious scholarly study of a design subject? Libraries, certainly, and students may be assigned to read the books, but only the most general overviews will be recommended by course leaders for student purchase since graphic design history will only be a minor component – not always undertaken willingly – of a graphic design degree. An editor of visual books told me recently that in her company’s experience even commercially promising graphic design books often struggled to sell 1000 copies. To make money, routinely priced, well illustrated books need to perform much better than that. The development of graphic design history is at root an issue of funding and always will be.

As a professional group, graphic designers are a slightly anomalous demographic when it comes to book buying. No other sector is more concerned with the production and design of books, and this aspect consequently comes to assume what might seem – from outside design where content usually comes first – to be a disproportionate importance. At present, the most committed and adventurous publisher of graphic design titles is Unit Editions, founded in London ten years ago by Tony Brook and Adrian Shaughnessy, partly out of frustration with trade publishing’s heel-dragging approach to design books. Unit has had some notable successes with monographs about Total Design, Herb Lubalin, Paula Scher and others. The books are lovingly designed and Unit has made astute use of Kickstarter to fund several titles. As designers themselves, Brook and Shaughnessy believe they understand their buyers’ interests and culture, and they have built up a devoted band of followers prepared to pay high prices for books that feel cared for and special.

While Unit’s style, confidence and panache have made mainstream publishers take notice, its ultra-focus on graphic designers as an audience confirms and potentially entrenches the inward-looking tendencies of the sector. Unit avoids distribution through bookshops (with a few exceptions) and online booksellers, preferring to sell directly, without loss of revenue, from its own website. The books are unlikely to be noticed by people in adjacent fields, such as art, photography, film, architecture and visual studies, and will be similarly off the radar for ordinary readers. This is a crucial issue within academia because the literature of graphic design, even when widely distributed, has often tended to be marginalised. As Annick Lantenois, a French design academic, writes in Graphic Design: History and Practice, ‘In France, the field of design and, particularly, of graphic design, has for a long time been, at best, ignored or, at worst, despised by cultural, artistic and academic institutions. French historiography has therefore excluded from consideration an entire section of practices and productions ….’

In Graphic Design: History and Practice, Shaughnessy reports that, by degrees and a little to his surprise, Unit ‘discovered an appetite among designers for books that dealt with neglected figures and moments in design’s past.’ Unit’s focus as a publisher switched from the contemporary, its starting point, to history. Shaughnessy argues that using practitioners as well as academics to write about history is one way to circumvent designers’ reluctance to read texts not grounded in practice and encourage them to engage with history. However, this kind of writing has long been the preserve of designers. Many of the most familiar names – Meggs, Heller, Hollis – have backgrounds in design and it is only more recently that figures such as Eskilson, an art historian, have appeared on the scene. Any call for more designer-writers simply reasserts the situation we have already. Graphic design history, as a still not fully formed academic discipline, remains in thrall to the needs of graphic designers. The field doesn’t ultimately depend on better designed design books (though good design helps). It depends on better researched and written texts.

Graphic Design: History and Practice, which deserves wider distribution, was the latest in a long line of calls for fresh thinking about graphic design history, going back to the three volumes of the seminal New Perspectives: Critical Histories of Graphic Design published in 1994 by Visible Language. The editors’ conclusion that designers and historians should work together to make graphic design history relevant to a wider audience seems surprisingly tentative and obvious after 25 years of discussion.

Elsewhere I have argued that graphic design history needs to break ‘out of the studio’ if it is ever to develop into a freestanding discipline. I proposed an alliance with the academic field of visual studies, or at least a movement in that discipline’s direction. Graphic design urgently needs to be scrutinised by observers who are not graphic designers and can bring other disciplinary perspectives, social and ethnic backgrounds and life experiences to the discussion. While these initiatives might choose to take the nature of practice into account to achieve a nuanced understanding, they should not be constrained by professional concerns and objectives.

Dead end or diversity

We are caught, however, in something of a ‘Catch-22’. Taschen’s spectacular smorgasbords are both an enjoyable celebration and a dead end; they move us no closer to achieving deeper insights. Major published research in the form of books, articles and digital media is the only way to build credibility and presence for the field alongside other academic disciplines. Women in Graphic Design 1890-2012, edited by Gerda Breuer and Julia Meer, is a good example of the type of revisionist research that truly expands our understanding of graphic design history. But this kind of publishing can only happen on the scale and with the diversity that is needed – at a time when there are increasingly insistent calls to ‘decolonise’ design – if an audience can be shown to exist to make it financially feasible. At present, that audience is still primarily composed of graphic designers. Can we find a way of uniting the visual qualities that make books attractive to designers with the probing research required to establish graphic design history as a territory of much wider interest?

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, Professor of Design and Visual Culture, University of Reading

First published in Eye no. 98 vol. 25, 2019.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 98 looks like at Eye Before You Buy on Vimeo.