Autumn 1996

Type fashion fusion

A stylist, a photographer and a typographer celebrate the look and feel of exceptional clothes

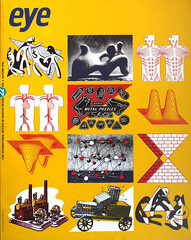

A series of 30 prints that manifest an unusually close visual synthesis between type and image are the result of a four-year collaboration between Peter Anderson, a typographer and print-maker; Platon, a fashion photographer; and Claire Todd, a fashion stylist. The three, who all trained in London as graphic designers, had no client or brief, just a strong motivation to see where the collaborative process would lead.

When Platon first began working with Peter Anderson, any potential uses for what they might create were far from their thoughts. ‘It struck me that what Pete was trying to do with type, I was trying to do with images,’ says Platon. ‘Both our work is intricate but with an economy of gesture; there may be many elements on the page, but all are necessary. I gave Pete some of my images just to see what he’d come up with, and he disappeared with them for four months. I thought the whole thing had fizzled out. Then I got a call from him, and when I saw what he had done, we all realized that it was something new. We decided to develop a visual language which explains fashion information in a new way, and blends typography and photography.’

Each image is inspired by a garment, chosen by Todd. Many of them, she explains, would not be featured in editorial fashion shoots – they are iconic, one-off pieces, and not integral to commercial collections. ‘This is paying homage to an individual garment, without having to worry about how it fits into a six-page fashion story.’

During the four years in which they have been working together, fashion has moved from grunge to glamour, and the three have become increasingly secure as a team. As a result, later images differ from the early ones in both content and form. ‘When we started, we used to try and impress each other by doing something as finished as possible,’ says Platon. ‘Now, Claire will bring along things that are almost unresolved, I will photograph things in a way that is almost unfinished, and Pete will do type that has room to be taken a stage further. It allows a little gap for someone else to come in, and that enhances what we are doing.’

Some of the images have been through numerous stages, with effects achieved in camera, during photographic processing, using etching, Letraset, computer typesetting and, finally, colouring. Most have been output on an Iris printer, giving continuous tone direct from digital data. Printed on to thick art paper, the images have a soft, almost luminous beauty, a result of Anderson working closely with a repro company, Quicksilver, to push the technology as far as possible.

Despite his evident sense of achievement with the Iris prints, Anderson emphasizes that it was the image which determined the process – whether in terms of originating the type or printing the image – and not the other way around. ‘I don’t use a process for a process’s sake,’ he says. ‘Whatever I’m trying to communicate sets what I use. It’s dictated by the subject matter. I’m anti-technique.’

With Anderson’s typography ranging from strident to sinuous, it comes as some surprise to discover that the words used are no more than the credits found on the fashion pages of any magazine. Far from seeing this as a cop-out, the three insist that it is essential to the project; that documenting everything from the name of the garment’s designer to the price of the model’s tights is all part of the narrative. ‘It’s really important,’ says Platon. ‘This isn’t about literature or poetry, it’s information design. It’s about telling a story about the dress.’ But if it really is intended as information design, then the project has a fundamental flaw. The images represent less a commentary on the fashion shown than a sensual response to it, and the information could only be accessed by the most determined viewer. Given the banality of what the words actually say, it seems unlikely that anyone will be that anxious to read them. If, on the other hand, the images are taken purely as visual poetry – as art – the emptiness of the words seems to reflect a lack of anything to say, as though the demand for expressive typography has outstripped the supply of ideas.

Nonetheless, as a self-financed portfolio piece, the project has done its job. Platon, Todd and Anderson have been commissioned by the Italian fashion house Moschino to create the advertising campaign for its couture collection this autumn. Maybe their work, once it has to function in the commercial world, will gain in conceptual depth, although whether it might also lose some of the refinement of these exquisitely crafted and subtly expressive images in the process remains to be seen.

Julia Thrift, design writer, London

First published in Eye no. 22 vol. 6, Autumn 1996

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.