Summer 1993

Video to go

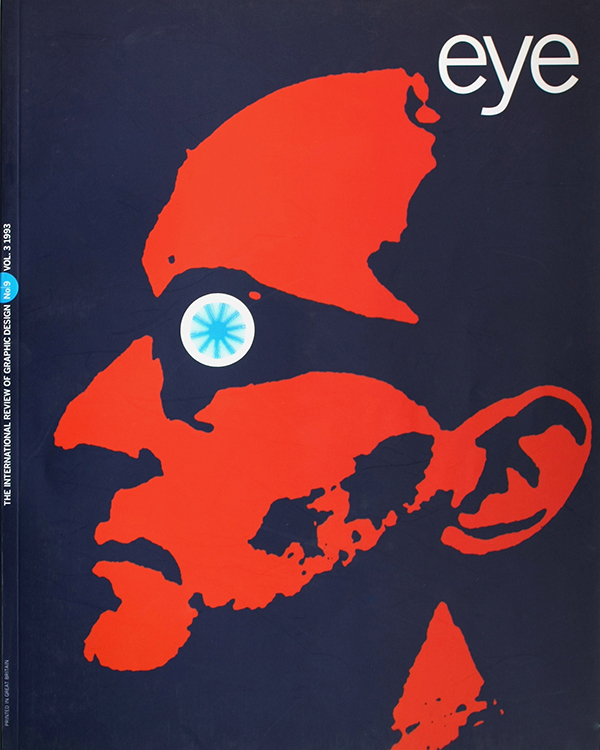

Saul Bass

Tomi Ungerer

Simon Esterson

Richard Amsel

Bob Peak

Kee Scott Associates

Colin Elliott

Video packaging is an area of graphics both marginal and ubiquitous. Who decides how it looks?

The sea of colourful packaging that fills the racks of video shops should be a rich display of intention and diversity by graphic designers and illustrators. Yet often it is nothing of the kind. Design for video sleeves has come to be determined by a range of conventions that position the video within a highly competitive market, rather than by predilections of an individual designer. Hemmed in by the different sets of codes required to market different movie genres, the design of video packaging, with some notable exceptions, is formulaic and safe.

For action and adventure of the Terminator type, steely gazes, menacingly brandished guns, speeding cars, explosions and other signifiers of machismo are much in evidence. For dramas and thrillers (Basic Instinct, say, or Sea Of Love) the images of the stars are superimposed on indistinct and moody backgrounds. For the new greed of softcore exotica ushered in by the successes of 9 1/2 Weeks, big hair merges with bedroom backgrounds, stare meets meaningful stare, lips pout and teeth gleam and bodies are teasingly revealed. Even comedies have their own predictable language: wacky, punning logos and a shot of the star mugging out of the pack – see Wayne’s World or Home Alone.

Of course, it could be argued that designing packaging for videotapes is little different from designing packaging for any other consumer product. After all, pack design for everything from polyunsaturated margarines to dog biscuits is shaped by the need to provide a mixture of information and brand values that help characterise the product for the consumer. But films have traditionally occupied a different cultural space: they are the end result of many creative processes and like books can be a point of departure to the world of the imagination. It is rare to find graphics on video sleeves which do justice to this idea.

The graphic languages which grew up with cinema were not always so hidebound. Corny as it may sound, there really was a golden age of film publicity when the ability of the commercial artist to convey the atmosphere of a movie through a telling graphic, typographic image, illustration or collage was a recognised as an important part of selling a film to its public. The interpretive freedom and lyric expressivity that characterise the work of Saul Bass in the 1950s, Tomi Ungerer in the 1960s and Richard Amsel and Bob Peak in the 1970s is largely absent from the authorless images that adorn video packs today. Most video sleeves lack the imaginative, organisational and illustrative charge to be found on the jackets of the best-designed novels. Perhaps it really is, as one creative director told me, a case of ‘to hell with art, let’s make some money.’

Brand loyalty

In an industry that loves the certainty of tried and tested formulas for storyline and characterisation, perhaps it should not come as a surprise that marketing and publicity techniques are formulaic too. Much of the reason for the predictable look of video sleeves lies in the need to ensure that the all-important brand image of the film is exploited whatever medium it is packaged in. so in the case of movies with big stars and name directors, backed by the financial muscle necessary for an international marketing push, all the promotional material harks back to the visual identity established for the original theatre release, in order to capitalise on the recall-factor, market penetration and brand loyalty already achieved. This branding extends to logos on posters, point-of-sale material, dump bins, store racks, T-shirts and baseball caps. For the most part, then, putting together a video pack is a question of assembling a bunch of second-hand marketing images. The authorial hand of the designer is usually the last thing on anyone’s mind.

A video release with a pack design which is not simply a miniature version of the original movie poster can nevertheless offer the opportunity for creative work which also takes account of the market. In packaging Ridley Scott’s 1492 Conquest Of Paradise for its video release, the London-based firm of creative marketing consultants Kee Scott Associates helped to reposition it through the simple insertion of a sword in front of Gerard Depardieu’s questing face. As a design solution to a promotional requirement solution suggested by the marketing department and the distributors, the move was successful: in playing up the action aspects of the film, the packaging broadened its appeal while retaining the core elements of its identity.

That particular sleeve is a deftly rendered example of the mainstream designers’ craft: a skilful blend of images and text that exploits to the full the capabilities of Quantel Paintbox and the Macintosh computer. The title block common to all 1492 material is overlaid on the composite illustrative image, electronically retouched to take the addition of the sword. The type incorporates a slight lateral stretch that mimics the effects of Cinemascope photography. The image of Depardieu’s face – although still obviously photographic – is both grainy and transparent, so the background of night stars can be seen through it. The kneeling figure on the clifftop, also recognisably Depardieu, was created through Quantel from a standing figure, and the whole lot was combined through the same system with the painterly illustration of a raging storm. It is a sophisticated piece of image manipulation, but it does not look like the work of a single designer with a personal view of what a video pack should do.

Design by committee

Computerised graphic tools have largely put paid to the jobs of individual commercial artists and illustrators in the video market. At various points in the last decade, Kee Scott Associates has employed up to ten full-time illustrators; now the company employs none. Before the widespread use of the computer, the role of the illustrator in the creation of a video sleeve was crucial. The task of combining the large amount of information required by the distributor on the relatively small area of the front cover of a video was often best achieved by airbrush and paintbrush. The miniature leaping Ninja, the New York skyline, the barrel of a gun, and the faces of the hero and heroine and the obligatory explosion / sunset could not have been convincingly or seductively rendered by cutting and pasting photographic images by hand. Employing a commercial artist or illustrator was the only way to create the melange of imagery needed to characterise the product inside the pack.

Today, manipulative computer technology can change the photographic image and yet maintain and even enhance the impression of verisimilitude. But the new technology has had other implications, including the fact that design by committee has become a feature of the process as designs are modemed across the Atlantic for approval by studio heads. As more and more films are made on the back of established star names, the importance of selling a movie or its video on a photographic likeness of the lead actor(s) has led to a downgrading of other illustrative components. Only one area of video pack design has maintained the key role of the illustrator in characterising the content of a film, and that is the horror market.

Creating an ideal image

Medusa Home Video is a Hertfordshire-based, independent film distribution and marketing company releasing some 50 titles a year, many in the horror sector. Independent companies have to bid for their films in the open market, and the acquisition of a title may not include rights to a suitable image with which to market the film. Colin Elliott, head of graphics at Medusa’s in-house design studio, firmly believes that time and money spent commissioning a sleeve can mean the difference between success and failure on the rental racks. ‘We employ a roster of about five artists who do all our work. And really, it works like Frankenstein: you create your ideal image, a man or a woman, from a range of parts. It’s something I think would be much more difficult to do photographically, especially if you’re dealing with the kind of images we get on our horror titles. Some feature little-known actors, so a photograph makes less sense than a good illustration.’

Such illustrations are value-laden selling tools designed to be read as flat images by the store buyers and as title sleeves by the punters. Since the first problem for the production company is to get the video into stores, rental sleeves are printed with a range of marketing information on the reverse to aid the initial sale to the buyer. Sometimes reversible covers will be manufactured to allow the store manager to pitch the film at two types of audience or simply to change the display.

The explosion in the video market in the past decade has created experienced buyers who know what will sell, or at least what will attract the eye of the customer. The only market research carried out on the success of a video pack is on whether the advance sleeve appeals to the practised eye of the buyer and subsequently whether or not a given video leaves the shelf often enough to justify its presence. Led by an idea of public taste developed about their target markets, successfully executed designs for horror, thriller, softcore and comedy titles achieve much the same aims as their mainstream counterparts. They transmit a huge amount of information, mood, atmosphere, and even storyline in the wink of an eye. Graphic design determined to this extent by the market can clearly come up with strong, complex, and engaging work. But often this work is defined by conditions which are in no way design-led.

Legal, decent, honest

Star billing may determine the relative sizes of the actors’ faces on the video pack and contracts may specify dimensions in percentage terms, together with the size of the title logo in relation to the credit block. The job of designers working on the latest hit releases is therefore often a case of creating an original design than of re-ordering chunks of information within tight parameters defined by a set of contractual obligations. In Britain, the design will also need to gain the approval of the Video Packaging Review Committee, an offshoot of the British Board of Film Classification, in association with the British Videogram Association, whose job it is to make sure that all video packs, like all advertising and promotional materials, are ‘legal, decent, honest and truthful.’ A video cannot receive its viewing certification unless the packaging design passes the VPRC’s scrutiny.

The video cassette and the box in which it lives constitute a curiously complex late-twentieth century object. The delicate and brittle plastic cassette is protected by a tough polypropylene or a homo-polymer box made from a recycled material durable enough to withstand repeated openings and closings. When in use, the average VHS cassette occupies a predominantly horizontal plane: it enters and leaves the VCR that way and we hold it in our hands and read its labels that way too. Put inside the box, the cassette changes orientation from horizontal to vertical and to all intents and purposes the cassette-in-box is treated as a book. Video boxes can be stacked book-like on the shelf and at a stretch the gentle curvature of the plastic spine can be made to suggest traditional book bindings.

The nature of in-store storage space and the different box sizes for different markets affect the ways video packs are designed and displayed. Rental boxes tend to be some 15 per cent larger than those for retail, primarily to differentiate between the two markets, while widescreen releases are often sold in large glossy boxes containing booklets and posters. You might think it logical that pack design would want to take advantage of the fact that when viewed in landscape, the proportions of the average video box mirror those of the cinema screen, but this is not the case. The book-style, portrait format continues to dominate because that is how most shelving in video stores is arranged.

The link between videos and books has been exploited by a few foil-blocked, embossed horror packs, but it is the packagers and distributors of art-house, cult and archive titles who have made the most of the positive associations between a library of books and a collected library of film titles. Bookshops in turn sometimes stock this kind of video. Esterson Lackersteen’s work for the London-based distributor Artificial Eye and Square Red Studio’s Connoisseur Video range for the British Film Institute operate in a different way to the work of Kee Scott or Medusa. The sleeves for quality and cult titles build on a set of sober conventions that can be traced back to Palace Pictures’ original Palace Classics line of the mid to late 1980s, the first art-house video series to be marketed in the UK.

Collectability and status

Martin Nash, at the helm of Connoisseur, sees the company’s release as ‘on a par with hardback books’ in terms of their collectability and status in the homes of those who buy them. Early Connoisseur titles like Wim Wender’s Wings of Desire sport designs by Geoff Wiggins which use elements of the language of expensive book design such as marbled paper and graphically rendered suggestions of quality bindings. Since Square Red has taken over, the vestigial traces of bindings and end-papers have been gradually modified until Connisseur titles are recognisable mainly by the clean white spaces which frame the stills and provide a neutral ground for clearly organised but still bookish typography. In the same way, Esterson Lackersteen’s Artificial Eye sleeves hark back to the rational typographic organisation, strong series identity and even the colour of the Penguin Modern Classics book covers of the 1960s and 1970s. The inclusion of a library number on the spine gives the buyer a nudge to complete the set.

Companies like Artificial Eye and Connoisseur are attempting something quite different to the major film studios and distributors. It is not quite a case of ‘to hell with money, let’s make some art’, but the specialist and often archival nature of many of their releases appeals more to the film buff than to the box-office blockbuster fan. The work of Square Red and Esterson Lackersteen assumes a desire on the part of the audience to know about the film rather than to be enticed by a seductive gaze or moody landscape. The integrity of the design and use of archival images imply these are objects of some worth, occupying a cultural space closer to the novel than their mainstream counterparts.

Didactic spirit

The grid-based typographic organisation of the sleeves anticipates verbal literacy on the part of the prospective audience, just as the reliance on unmodified stills from the films implies a high degree of film literacy. In effect, the buyer or renter is being flattered into making the purchase. The organisational clarity of the designs is flexible enough to accommodate full-bleed photographic images in colour or monochrome, quotes from reviews, synopses, credits, logos, bar codes and copyright information. Connoisseur and other companies use the usually blank inner sleeve to provide detailed credits and a short critical essay in the same didactic spriti as the old-fashioned sleeve note on a jazz or classical record. Obviously the design is market-led to some extent, in that it is intended to appeal in a specific way to a specific audience. But without the pressures of mainstream marketing, video buyers’ recommendations and a compulsory set of globally implemented images, the titles on which Square Red and Esterson Lackersteen concentrate offer the designer a much greater degree of freedom to build a direct relationship with the buyer.

It is ironic that as the designer of mainstream video sleeves, distributors and marketing managers refine their language towards an authorless smoothness, the future of the medium is uncertain. Just as the book is said to be under threat from a new wave of digital technology, so the videotape is set to be replaced in the latest wave of centrally planned technological obsolescence by HDTV and the interactive CD-Rom movies in which the viewer delivers the plot. Perhaps when this revolution occurs and the mainstream movie has finally adopted the same anonymous quality as the packaging it comes in, the state of the art will be thought to have reach perfect equilibrium. In the meantime, I am tempted to recommend a good book, or at least a video that reminds you of one.

Michael Horsham, design historian, London

First published in Eye no. 9 vol. 3, 1993

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.