Summer 1993

White space black hat

Derek Birdsall harbours a secret. It has given him 30 years at the top. If it works, he says, use it again

Winter in London. Derek Birdsall, acclaimed English designer of books and magazines, sweeps across his large and distinctly chilly Islington studio dressed in a black hat and black scarf. A large bearded man in his late 50s, framed by dusty shelves holding volumes and objects of every description with long lines of fastidiously arranged layouts stretching away into the distance, he fills the space with his presence.

‘You need a lot of space to do the work we do,’ gestures Birdsall with the kind of bohemian flourish that has made his such a visible presence on the British graphic design scene over the past 30 years. ‘You need to be able to show the client that you have the physical capacity to handle a book of 500 pages or so.’

This is the home of Omnific Studios, the design firm Birdsall runs with his partner Martin Lee, a production man. The most high-tech piece of equipment in the place is an electric typewriter. In a world of screens, bytes, and digital fonts, Birdsall designs books in the traditional way. And to judge by the commissions he receives, publishers – especially in the art world – like him all the more for it.

Birdsall chose the name Omnific, whose latest incarnation he founded with Lee in 1983, because the idea of a design studio bearing its founders’ names made him nervous. He had a chat with Herb Lubalin and decided that words starting with ‘O’ or ‘Q’ sounded nicest. Birdsall combed the dictionary, dallying over Quarto and Octavo before choosing Omnific: ‘It’s nice looking and it meanings all-creating.’

In a sense Birdsall is all-creating, a man of great drive, girth, good humour and appetite for life who insists on moving on to the next challenge and not dwelling on the past. When we meet, he had just been sacked from four years as art director of The Independent Magazine following the departure of editor Alexander Chancellor to the ‘Talk of the Town’ section of The New Yorker. The sober monochrome and simple typography of The Independent Magazine was a complete departure for British colour supplements and introduced Birdsall’s work to a new, younger audience, but its designer is not shedding any tears. ‘We had a good run,’ he insists, preferring to bask in the critical acclaim received by his design for the epic volume The Bauhaus: Masters & Students by Themselves, edited by Frank Whitford.

Birdsall sent a copy to Paul Rand as a Christmas present and shows me the note he got back. It is glowing with praise and means a lot to a designer who identifies as much with the era of late 1950s US design that Rand represents as with the pioneer spirit of the Bauhaus.

‘I’m fond of telling people I was born just a year after the Bauhaus folded,’ says Birdsall. (He was born in Yorkshire in 1934.) ‘My first instinct when asked to design the Bauhaus book was to avoid doing so-called “Bauhaus” typography – in fact, there’s no such thing. That meant no sans serif type. Instead, I used Walbaum, which was cut in Weimar around 1805. The Bauhaus was in its own way a perfectly conventional art school –a hotpotch of styles, lifestyles and beliefs out of which some recognisable characteristics emerged. One of the most curious discoveries in doing the book was that an early Bauhaus emblem contained a swastika – well before the Nazis arrived. As designers, we tend to pluck from history those things that suit us. My first and best idea was that the book should look like itself.’

The Bauhaus book illustrates one of Birdsall’s most cherished views about what he calls ‘design redundancy’. He looks back to a time when printers produced elegant books without any need of an external ‘designer’ and strives to achieve simplicity and even a certain obviousness of effect. If a design works, says Birdsall, then there is every reason, whether it is your own or someone else’s, to use it again. Articulate and literate, he is highly suspicious of individual designer styles or fashions and is rooted in the classical influences which shaped his training.

Birdsall showed an early ability to draw and one of his strongest childhood recollections is of stationery shops full of pens and piles of trimmed paper. His grandfather was a clerk in the local chemical works, a respected figure who was an expert on writing instruments and who would use an agate (a semi-precious stone) to make up to ten perfect carbon copies of documents.

‘I delighted in finding special tools for special jobs,’ says Birdsall. Early on he recognised that the school system judged intelligence on the quality of a pupil’s handwriting, so just before his scholarship examination at the age of 11 he deliberately broke the nib of his pen so that he would be given a new one and would be able to write more clearly. He marched triumphantly into grammar school only to be ‘outclassed academically and thoroughly miserable.’ Talent at art and design was a consolation, however, and at the age of 13 he spent the enormous sum of £15 on a printing press.

Birdsall enrolled at Wakefield College of Art in 1949 for a three-year foundation course. He won a scholarship to the Central School of Arts and Crafts where he studied under typography tutor Anthony Froshaug in a department called Book Production and Commercial Design. ‘The inference was that good book production naturally included design,’ says Birdsall, ‘Graphic design, of course, is a curiously meaningless term. I toyed with the idea of renaming the graphic design course at the Royal College of Art, “Book Production and Commercial Design” when I was a professor there in the 1980s.’ Birdsall was also tutored at the Central School by the artist Richard Hamilton, then resident in the industrial design department. Terence Conran and Colin Forbes had just left; Eduardo Paolozzi and many other key figures were contemporaries. ‘This is a chapel of good taste,’ intoned head of department Jesse Collins when the occasion demanded. ‘Out there are the barbarians.’

Between 1955 and 1957 Birdsall did his National Service in an army printing unit. He was posted to Cyprus during the Suez Crisis, when he received magazine cuttings and books ordered from Penguin booklists sent by his wife Shirley, a childhood sweetheart. Back in civilian life he was offered a position as a typographer in Crawfords advertising agency for £13 a week. Bravely, in such an austere time, he held out for a better offer. That came in the shape of regular freelance work from John Commander, the art director of printers Balding + Mansell, who offered him the job of designing a series of programme notes for opera records at 16 guineas a boxed set. So began a long, eccentric and distinguished freelance career. ‘I’ve never been employed in a job, ’ says Birdsall. ‘I’m like my father, a labourer, who was also unemployable.’

To supplement his freelance work, Birdsall began lecturing in the history of typography at the London College of Printing. In 1960 he joined forces with three other designers: George Daulby, Peter Wildbur and George Mayhew, a designer who had done a lot of work for Joan Littlewood’s Theatre Workshop company. The team, named BDMW Associates (acronyms were new and progressive in those days), took up residence in a Bloomsbury loft. ‘This was groundbreaking stuff,’ says Birdsall. ‘Apart from Design Research Unit, who were the gods, few design groups existed.’

A book published in 1963 by Balding + Mansell entitled 17 graphic designers London shows the work of BDMW alongside the likes of Alan Fletcher and Jock Kinneir. It includes a photograph of a young, clean-shaven Birdsall peering aggressively into the camera. ‘The book was an attempt to sum up what London had to offer in graphic design,’ says Birdsall. ‘There was an accompanying exhibition which I designed. Out of that nucleus of people came the idea for D&AD [Designers and Art Directors Association] with its annual exhibition and publication. We wanted a counterbalance to the Society of Industrial Artists [today the Chartered Society of Designers] which was largely based in industrial design.’

Birdsall was highly mobile and highly visible during the 1960s. ‘I did a bit of everything – from packaging to television commercials,’ he recalls. ‘But there was no sense that it was a “swinging” area. It was simply a case of jumping from one plank to another. You’d hear someone was doing something interesting and you’d get involved. Today the scene is more specialised, you can’t cross over disciplines so easily. Marketing has taken over from design.’

One of the factors that helped such a magpie approach was that the graphic design community in the 1960s was small. Birdsall recalls: ‘There were only about 20 graphic designers seriously intent on survival. There were fewer opportunities but less competition than now. So it was roughly comparable. I agree with whoever it was who said that genius is in the same proportion in every age.’

Birdsall’s involvement in magazine art direction began early on. He worked briefly at Town, where he took over from Tom Wolsey, and put in another short stint at Nova after its original art director, Harri Peccinotti, moved on. Birdsall and George Mayhew did the dummy for the original Telegraph magazine and Birdsall was later to create the original format for the Observer magazine. For six months in 1968 he worked in Munich with Willy Fleckhaus at Twen. It was through Bruce Bernard, the first picture editor of the Sunday Times Magazine, that Birdsall was introduced more that 25 years later to a fretting Alexander Chancellor, who gave him one week to design the dummy for The Independent Magazine.

In 1964 Birdsall formed the forerunner to Omnific Studios with Derek Forsyth, the advertising manager at Pirelli. Dennis Hackett, editor of Nova, and Denis Curtis, production director of Town, joined the new design firm as consultants. Immediately Birdsall designed the first Pirelli calendar. He used the Beatles’ photographer Robert Freeman to set a Pirelli style based on the female form that swiftly became one of the visual icons of the era.

When Birdsall and Forsyth fell out at the end of the 1960s, Birdsall handed over the Pirelli account to Forsyth. But there were other clients who would give him the creative freedom to remain at the leading edge of international graphic design. IBM commissioned him and remains a client today. Mobil Oil involved him in books and catalogues which were part of its programme of cultural sponsorship. When two Mobil executives left to join United Technologies, Birdsall found a rich new source of work, again in the field of arts sponsorship.

Birdsall has worked with some of the most familiar and famous fine arts images and feels it has been a privilege to design with such material. When we meet he is wrestling with translation problems for his latest fine art commission, a massive catalogue for ‘Fabergé: Imperial Jeweller’, an exhibition which will open in St. Petersburg in June before traveling to London’s Victoria & Albert Museum in 1994.

He also originated book projects on subjects which interest him: in 1972 he designed and produced Fischer v Spassky Reykjavik, going to press just 24 hours after the final chess game. He followed that up with A Book of Chess (1974) and The Technology of Man (1980). It is also true that he seems to get the best results from subjects he feels sympathy with, such as the Bauhaus or the Shakers. Shaker Design won a gold award from the New York Art Directors Club in 1987, just one of many prizes in a career which shows no signs of flagging.

Currently he is working on a how-to-do-it book about his own work. Provisionally entitled The Intelligent Book, this drawer full of handwritten notes will one day be transformed into a large-format compendium of Birdsall tips on everything from typefaces and typesizes to papers, grids and impositions. For example: column widths should be chosen to be most useful for illustration, not text, then the size of typeface and leading selected to be most appropriate to the column width.

‘White space is the lungs of the layout,’ booms Birdsall over my shoulder. ‘Clients don’t understand the function of white space. It’s not there for aesthetic reasons. It’s there for physical reasons. I want to do this entire book without a single reference to aesthetics. ’

Birdsall believes that his own design methodology can be taught. In that way he shares an approach with Paul Rand: ‘It’s no secret that Paul Rand is a brilliant teacher. Gert Dumbar and Bob Gill are brilliant designers but you can’t teach their kind of thing. ’ Both Gill and Dumbar were graphic design professors at the Royal College of Art before Birdsall accepted the position in 1987. ‘I’d turned it down before and didn’t think I’d get offered such a super job a third time, ’ he says.

His time at the RCA brought him face to face with the college’s pugnacious rector Jocelyn Stevens, who had just finished a bruising quarrel with Dumbar. Birdsall is characteristically sanguine about his two years there: ‘I’ve always enjoyed teaching and I loved my time there. I brought in a lot of good staff, but in the end I had a big row with Jocelyn. I didn’t think it was right that someone in his position should be so rude to someone in mine, so I left. If I wasn’t going to stand up to him, who was?’

In a sense, Birdsall’s attitude to Stevens reflects his belief that if you can’t please the client then you should quit. ‘In a curious way I am the client’s man. You can’t impose a solution on a client. If you can’t make him or her happy then you should resign the job. Jocelyn was jus another client to me.’

Birdsall’s supremely elegant and mature design solutions, rooted in the English tradition of classical, legible, understandable typography, are a refreshing antidote to all those rampant decorators and historicists of the 1980s. And he is still busy while many of them are not, displaying a nonchalant ability to handle the biggest projects without the aid of any of the new whizzbang technology. He is clearly enamored of his latest partnership arrangement, in which Lee, a former stalwart of Westerham Press, handles the business and production side while he concentrates on design. Omnific has four staff: apart from Lee and a Spanish designer Pepe Sala, Birdsall’s wife and daughter run the practice. His two eldest sons are builders, constructing a new chapel-style home for their parents adjacent to Omnific’s Islington studio; this is designed by Theo Crosby of Pentagram and is full of the architectural equivalent of white space.

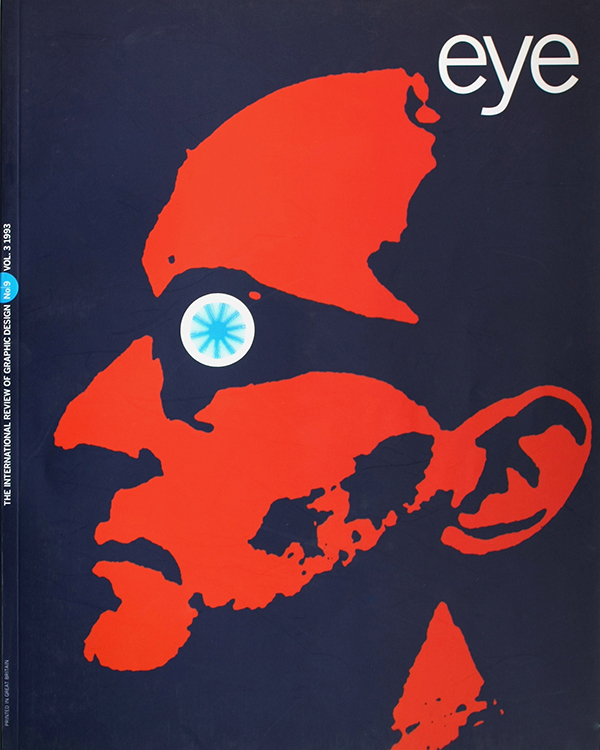

When Birdsall was designing the weekly covers for The Independent Magazine he became known for the catchphrase ‘How often do you get the chance to put Elvis on the cover?’ So when he was fired, his leaving card showed his distinctive profile with the coverline ‘How often do you get the chance to put Derek Birdsall on the cover?’ Birdsall is amused. He knows his worth, but above all has a sense of proportion about what he does.

‘I admire people like Paul Rand, Alan Fletcher, Bruno Munari and Henry Wolf,’ he tells me, tilting his black hat with finality. ‘I am attracted to ideas that can be explained. Otherwise you are an artist and I’ – here he pauses with a practised sense of timing – ‘I am no artist.’

Jeremy Myerson, design writer, London

First published in Eye no. 9 vol. 3, 1993

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.