Monday, 11:00am

16 December 2019

Among the spirits

Nadav Kander’s poetic and mysterious portraits of celebrities steal the limelight in his new book The Meeting. Photo Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for Eye magazine.

Nadav Kander’s The Meeting (Steidl) collects 217 of his portraits, made, with the exception of just one self-portrait, since the 1990s. The self-portrait is revealing, and no doubt this is Kander’s intention, because it shows how his later approach to portraiture was there in embryo, in 1982, before he decided around 1996 to move away from advertising, where he made his name, and seek editorial projects. The black and white portrait of the artist as a young man reading a newspaper is beautifully lit and composed. It possesses gravitas aplenty and Kander, in this shot, is still only 21.

The Meeting has some brilliant photographs. It invites and sustains repeated viewing and there are images I will never tire of seeing. At the same time, it is something of a mixed bag, blending styles of representation and types of subject – documentary pictures, family pictures, August Sander-like dispassionate studies, photogenic unknowns and portraits of the famous – that don’t always fit together comfortably. If the book were a critical study that sought to show Kander’s range and development, these jumps would be fair enough, but in an intuitively composed photobook with minimal explanation the wandering focus weakens it visually as a collection. I repeatedly found myself dwelling on the high-wattage celebrities at the expense of photographs of ordinary people who would fascinate in other contexts.

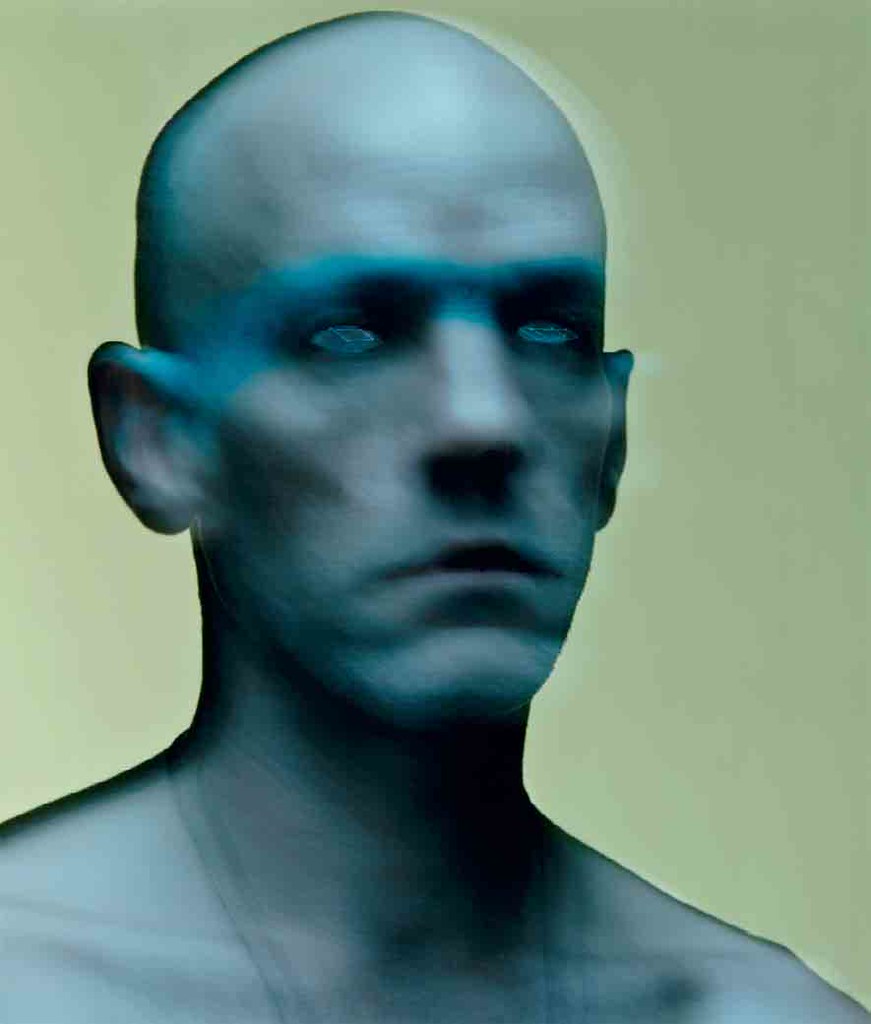

Keira Knightley VI, London, England, 2014. Top. Michael Stipe I, Chicago, 2003. All pictures from Nadav Kander’s photobook The Meeting, Steidl, 2019.

The celebrities do bring out the best in Kander. They are public figures and performers who are totally at ease in front of the camera. If they are actors, singers or models, their faces are central to their appeal; they have remarkable, bankable features and will look magnetic in almost any picture. Yet Kander often discovers more. In his obscurely threatening study of Michael Shannon, the dapperly attired American actor tilts his head forward while looking upwards, drawing attention to his huge, intense eyes. A Google image search found nothing to equal Kander’s portrait. For a picture of the British actor Rebecca Hall, Kander slides in close to give maximum emphasis to her parted lips and fleshy facial features, tentatively framed by her hand and her informally styled hair. The intimacy feels almost intrusive. She appears to be distracted and then we recall her craft: is she merely acting ‘lost in the depths of thought’?

Rebecca Hall I, London, England, 2011.

Kander’s most affecting pictures tend to be close collaborations with highly knowing and pliable subjects. The more these luminaries allow him to intervene and manipulate, the more compelling and akin to the open-endedness of ‘poetry’ – a word Kander favours – the images often become. Led Zeppelin front man Robert Plant slumps over a table in a corner, toying at a plate of unspooled cassette tape with a fork: a strangely demoralised view, we might think, of his musical legacy. Confronted by Rosamund Pike, Kander projects a tracery of tree branches onto the Hollywood star’s face and bare shoulders, like a network of veins and arteries drawn to the surface and vulnerably exposed to the public’s gaze. In the book’s weirdest pair of character interpretations, Michael Stipe is transformed into a blue-skinned visitor from a distant planet and something alarming and unfathomable has happened to his eyes.

Barack Obama III, Washington DC, USA, 2012.

When coming on this strong is not an option – when, say, photographing the Prince of Wales – Kander is more dependent on his subjects. While the future monarch acquits himself well in full close-up, as does Barack Obama, pictures of Salman Rushdie, Judi Dench and even a seasoned campaigner like Paul McCartney lack spark. The ‘alien blur’ manoeuvre seems all wrong for the very worldly David Beckham, and fashion maven Victoria Beckham receives a surprisingly insipid silhouette treatment. Kander’s liking for superimposed imagery works perfectly for Tricky, producing two murky and troubled portraits of the singer – both with shadowy doppelgängers – but with Jonny Greenwood the interpolated figure of a boy feels superfluous, muting the impact of the Radiohead guitarist’s floppy dark hair and wide-jawed face. This is an instance where Kander’s device may have made sense in the original place of publication – presumably the boy is Greenwood’s son – but the book gives no details of where this, or any, of the commissioned photographs first appeared.

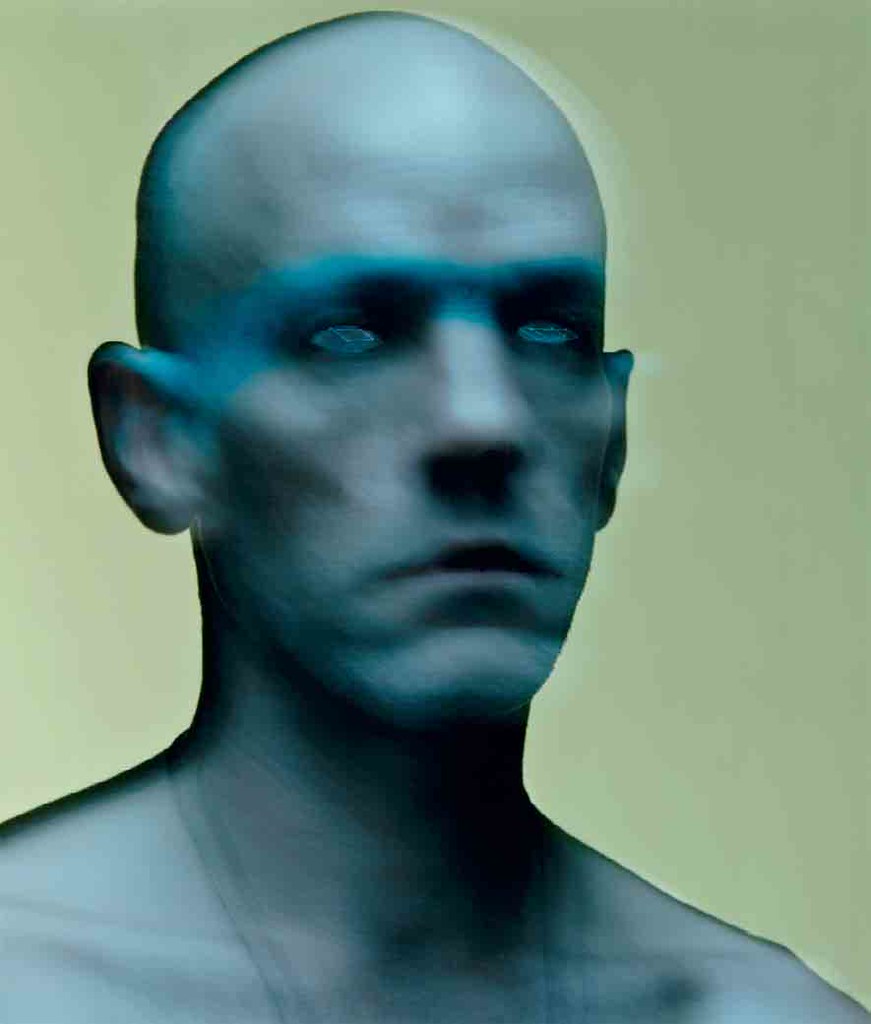

Mark Owen, London, England, 2010.

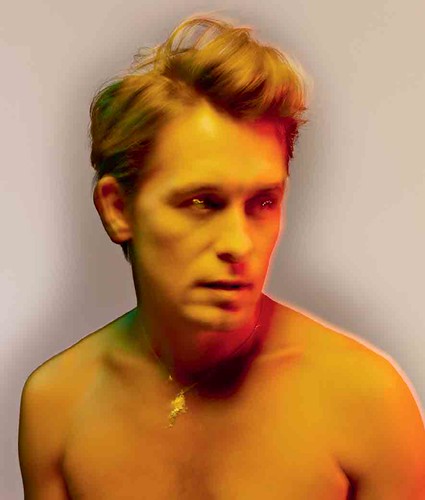

In a conversation with David Campany, Kander cites Man Ray as an influence and some of his pictures use an updated version of the American pioneer’s solarisation technique, endowing subjects with an otherworldly dark outline, like an electrical crackle of charisma. Kander talks about how, when he was young, he loved how uncanny and uneasy some art made him feel (he says Dada but it sounds more like Surrealism) – ‘as if I was amongst spirits while looking at it’. This zone feels like Kander’s natural habitat. The actor Vinette Robinson lies on the floor with her limbs levitating as though possessed by a controlling spirit. Kander’s artist sister, Tamar, becomes an ultramarine phantom caught in front of one of her own colourful paintings. Patrick Stewart appears to howl like a mentally disturbed monk. Is this entirely a piece of artifice, a performance for the camera, or is Stewart calling up some normally hidden dimension of himself, or of Kander, or of us? The question arises with many of Kander’s most provocative portraits. He wants the viewer to complete the triangle of meaning formed with photographer and sitter by filtering the picture through our own state of mind.

Rick Poynor writer, Eye founder, Professor of Design and Visual Culture, University of Reading

Patrick Stewart II, London, England, 2012.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.