Summer 2017

Beyond context

Mysterious equipment, unknown officials and arcane activities combine in a photobook that is testament to the art of selection and editing.

Photo Critique By Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for Eye magazine.

In a recent poll of photographers and photo experts organised by Source magazine to reveal the ‘greatest photobooks of all time’, there was an unexpected outcome at the top of the table. This wasn’t the winner, Robert Frank’s The Americans (1958), a certified classic that gained 27 votes. The surprise title, selected by eighteen respondents, occupied the second position. Constructed from archival images, Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel’s Evidence contains no original photography by the artists. Since its publication in 1977, the book’s reputation as a key document in the development of conceptual photography has kept on growing. Distributed Art Publishers reprinted it in 2003 and it was reissued in 2017.

The ‘evidence’ takes the form of 61 black-and-white photographs presented one per page in an unbroken sequence. It is obvious that many of the pictures relate to research, investigation or industrial processes, but there are no captions anywhere to illuminate what we are seeing. The precise nature of the events is often unclear and many of these scenes, if viewed in isolation, would be baffling; in one picture, a man looks through a small aperture into a white room where two shallow trays are suspended from a pulley system. Any pictorial sequence, though, has the potential to suggest a narrative. While there are visual links both within some spreads and from one spread to the next, there is considerable latitude for interpretation.

In retrospect, it is remarkable that Sultan and Mandel were able to secure these pictures for their own slyly questioning purposes and it seems unlikely that this kind of initiative would elicit such unsuspicious cooperation now. Armed with a government grant to pursue a research project leading to an exhibition, the photographers convinced corporations, laboratories, police and fire departments and government agencies to permit access to their photographic records.

For three years Sultan and Mandel visited more than 80 institutions, all listed in the book. Evidence’s featureless, official-looking cover and serif typography reflect their bureaucratic detachment and ostensibly objective stance.

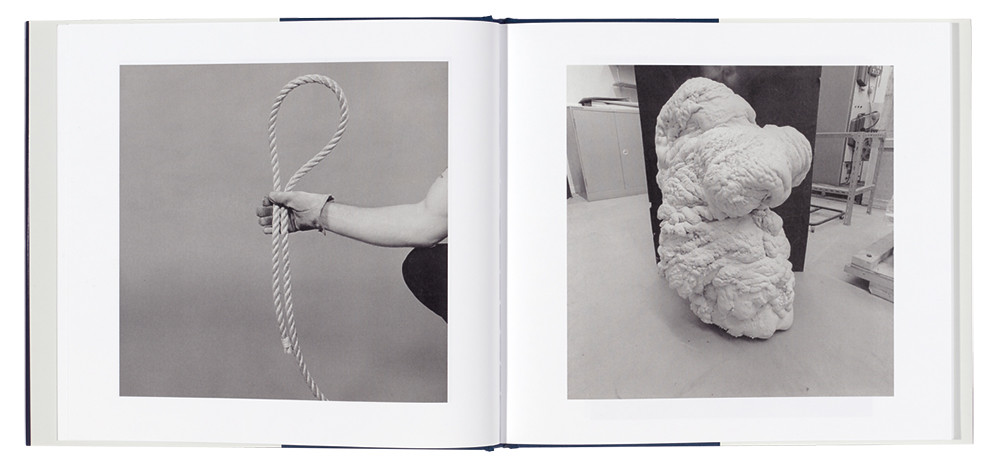

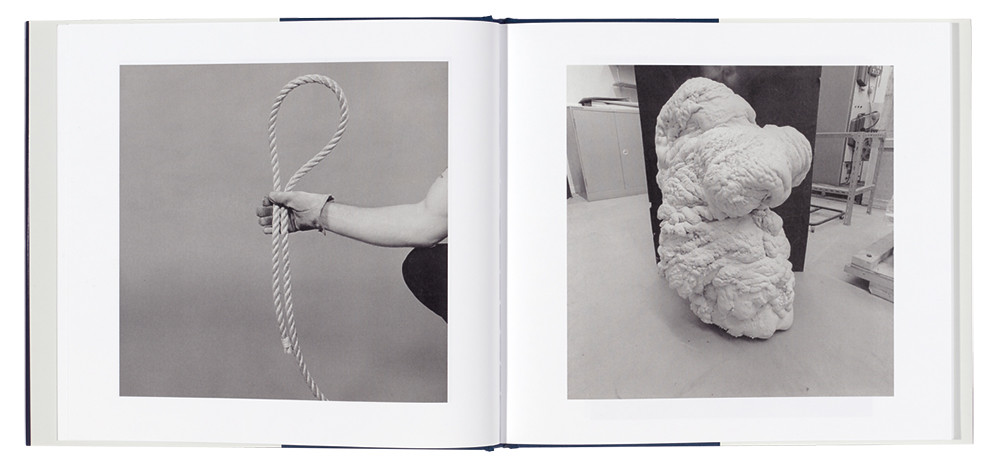

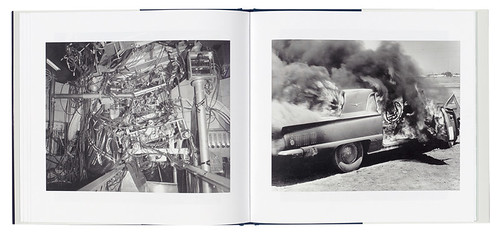

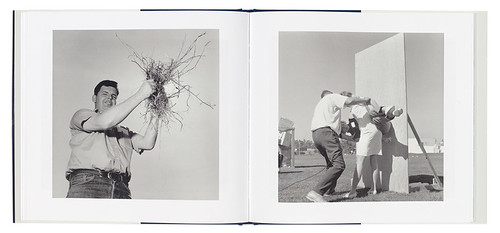

Spreads from Evidence by Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel, reissued by Distributed Art Publishers, 2017.

In recent decades, we have embraced the possibilities of found and vernacular photography for repurposing. Websites invite found submissions, extensive private collections have been published, and artists use found images in their projects. It is widely recognised now that anonymous non-art photos can provide experiences just as resonant and art-like as pictures shaped self-consciously by an artist. Transplanted from their original files and reports, where they were supported by contextual information, technical analysis and other related photos, the pictures in Evidence have acquired a strangeness, an absurd humour, and a sense of disturbance and threat they didn’t possess for the men – and it is mainly men we see – who used them pragmatically while carrying out their jobs.

Whatever their original intention and meaning may have been, their evidentiary value has flipped and the photos have become signs and indications of something gone awry. In one scene, a group of nine men stand on a ridge framed portentously against the sky, gesturing with authority at something huge and unseen. Disembodied hands demonstrate a length of rope, a disposal bin, the depth of a hole, or measure a zone of damage on a wall. The artists show an unfathomably complex piece of machinery interlaced with hundreds of looping wires and in the next image, like a warning about the hubris of technological systems, a stationary car explodes into flame. In the book’s most troubling scene, a leather-gloved hand smothers a monkey’s head – the creature’s partially shaved skin looks almost human.

There are also repeated images of entrapment. A figure concealed inside a pressure suit lies face down on the carpet and men in hard hats wade uncertainly through a sea of foam. An investigator carrying a black box appears to be struggling to escape from a deep basement, although there is a ladder behind him. The book’s final image of repression, devoid of overt human traces, shows a barren pile of rocks tightly clamped under a wire mesh.

Evidence is a masterly feat of selection and editing. Sultan and Mandel sifted through hundreds of thousands of photos to arrive at the final sequence. In the later editions, a spread showing a group of outtakes gives an impression of the qualities an image needed to make the cut. The also-rans provide a little too much information. They are not sufficiently abstract to float free and take on other meanings. By comparison, the pictures in Evidence are so purged of distraction and elliptical that the artists might have shot them for the task.

All of the anonymous photographs are captionless, leaving the viewer to decide what is being shown.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, Professor of Design and Visual Culture, University of Reading

Published in Eye no. 94 vol. 24, 2017

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 94 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.