Friday, 11:00am

10 March 2017

Double satori

For photographer Sergio Larrain (1931-2012), making pictures was a form of spiritual quest. Photo Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for eyemagazine.com.

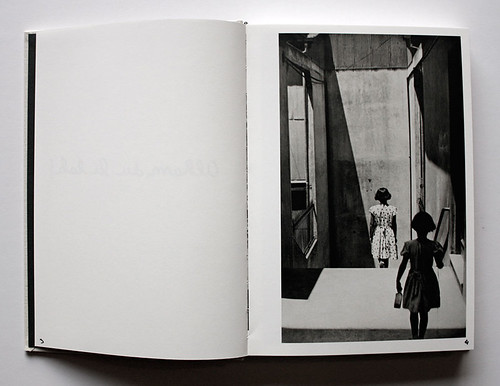

Sergio Larrain’s book Valparaíso, first published in 1991, opens with a picture of ineffable mystery taken in 1952 when the photographer was just twenty years old. Two girls, who could be sisters, are walking away from the camera and although no steps can be seen it is obvious they are descending, with the photographer positioned slightly above them. The girls have the same bobbed hairstyle and both wear short-sleeved dresses so that the nearer girl seems almost like a younger duplicate of the other. The partially enclosed space has a complex vertical geometry and the structure casts a long angled shadow that clips the first girl, accentuating her descent. In a few seconds’ time, she will have disappeared from view and the second girl will occupy the same position.

Larrain knew at once that he had produced a magical image and the picture is one of his masterpieces – it was used on the cover of the justly lauded monograph Sergio Larrain: Vagabond Photographer, published in 2013. Thames & Hudson’s follow-up, a new edition of Valparaíso, is a much expanded version of the French publisher Hazan’s highly collectable first edition, copies of which now sell for more than £1000.

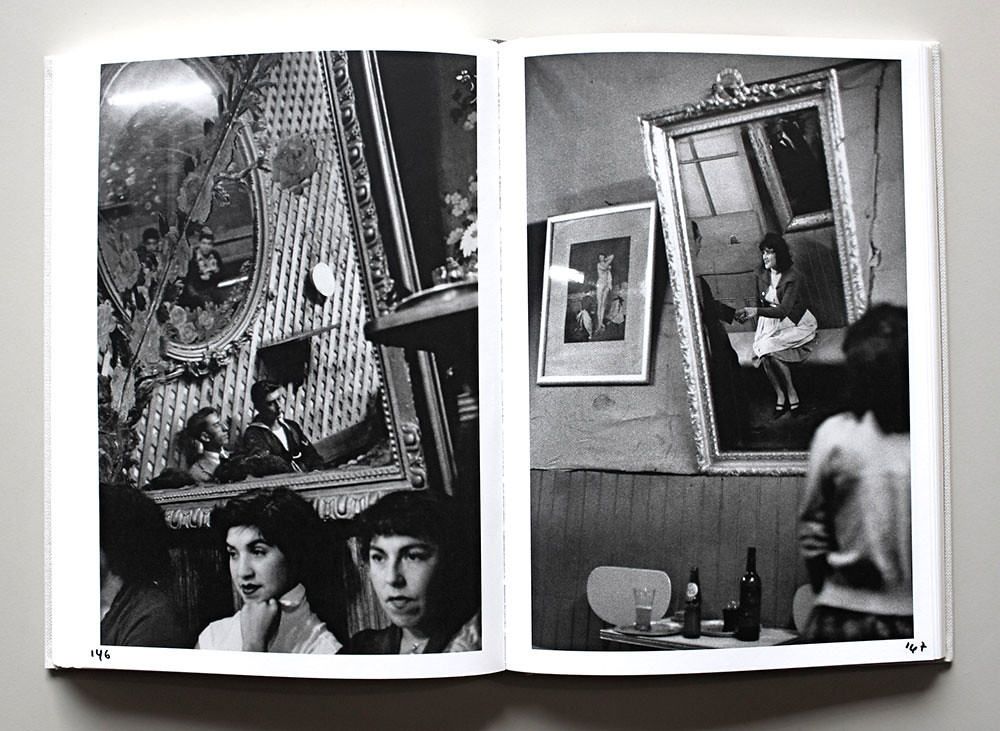

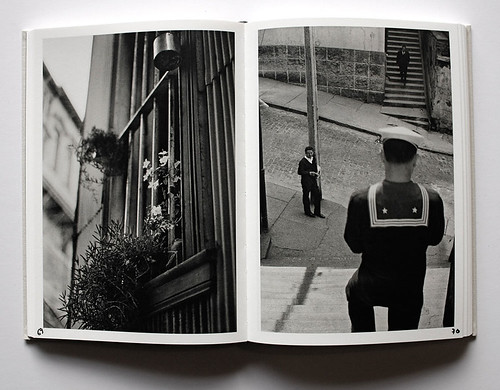

All photographs were taken in Valparaíso, Chile. Date unknown (left) and 1963.

Top: 1963 (left) and 1957.

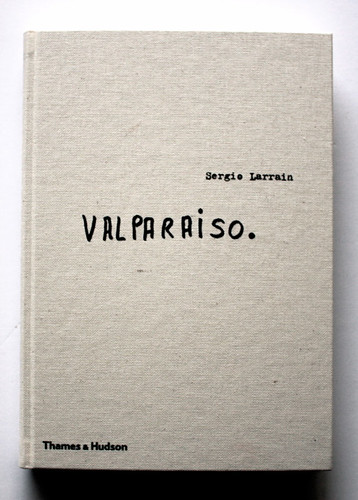

On the original typographic cover, the letters of Valparaíso drop down in regular increments like steps, an indirect allusion to the topography of the Chilean port city. To move around this steeply sited labyrinth, as Larrain records it, is forever to be labouring up and down the hill, or perhaps to spare the feet by taking the funicular. Of the 38 pictures in the first edition, steps appear in ten of them and in the revised version based on Larrain’s handmade layout – he died in 2012 – there are even more pictures of this kind; he continued photographing the city he loved until 1992. The book now benefits from a panoramic establishing shot of Valparaíso, a riot of rooftops sprawling over the hill above the vessels moored in the port.

Larrain’s remake, first published in French in 2016, was overseen by Agnès Sire, an old friend, who contributes an essay (there is also a text by the poet and politician Pablo Neruda). Now running to more than 200 pages, the book is substantially changed from the slender original. Larrain supplied notes written by hand and on a typewriter, his spelling in English often erratic, and even the page numbers are scribbles. Famously, after his early success as a roving photographer – for a while he was an active member of Magnum – he retreated into a life of mystical reflection, drawing on insights from Sufi and Zen. He wasn’t interested in photographs as reportage; what he wanted to discover with the camera, as with the rhyming girls, are instants of quietly fortuitous revelation. ‘Art is an approach to the state of satori,’ he vouches in wobbly letters. His modus operandi – ‘Opening the moment with the rectangle’ – is pithier than a haiku.

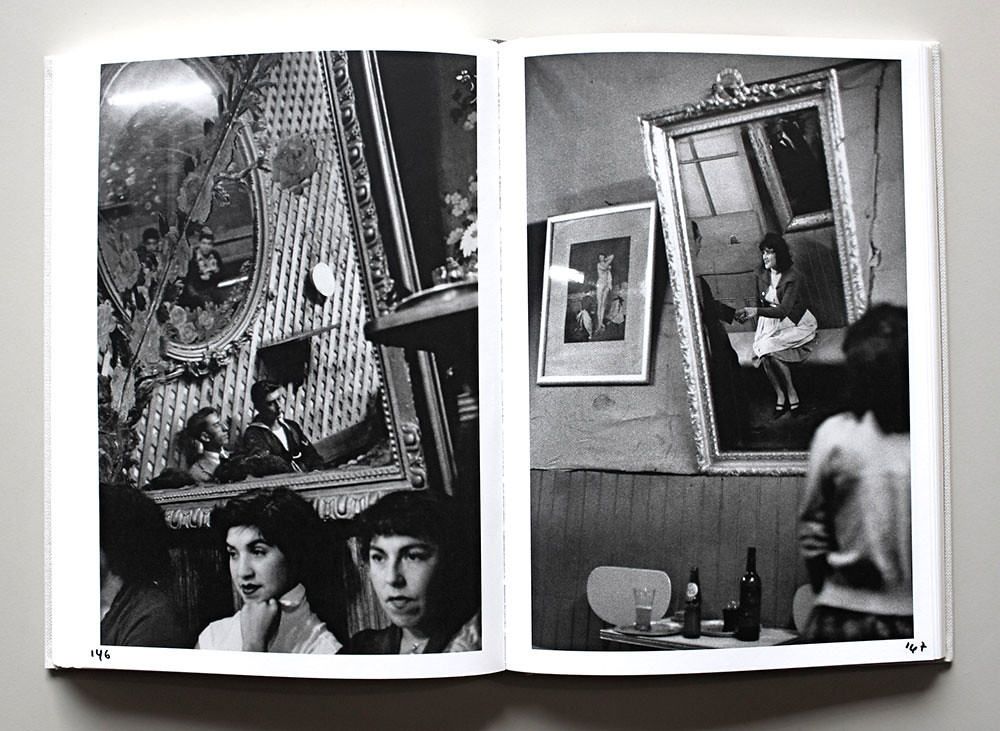

Larrain’s informal notes in the new edition.

1963.

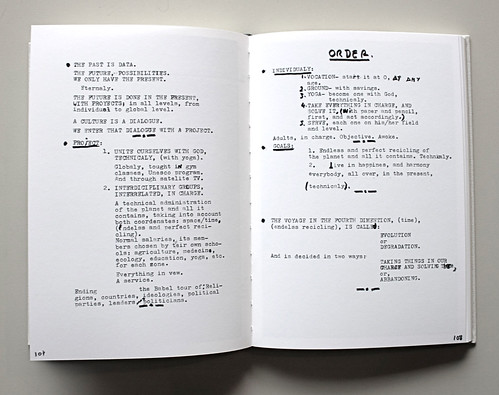

The typed-up notes amended by hand, covering subjects such as ‘The piramid [sic] of reality’ and ‘Reenchanting the planet’, give the revised photobook a troubled, tentative air. On his repeated visits to Valparaíso – ‘one of the most poetic places’ – Larrain saw a city being ruined by abandonment, poverty and crime, and for some photographers this would have been subject enough. He includes a scene of severe dilapidation with a broken toilet exposed to the elements, yet many of the new pictures alight on details of little consequence: flowers in front of a shutter, the shadow cast by a stone balustrade, leaves resting on a wall. For Larrain, these may have represented intimate moments of enlightenment and the persistence of Valparaíso’s poetry in spite of the ravages, but they are less remarkable as photographs and temper the intense human atmosphere of the original collection where he focused mainly on the city’s occupants.

1980.

Part of the original Valparaíso’s impact came from the editing and pairing of the pictures on a spread. None of these visual relationships has been retained and it is often hard to see the need for the alterations. In another of Larrain’s sublime tableaux of steps, a sailor, observed from behind, heads down to the street. Directly opposite him another man is also descending, while a third stands next to a lamppost below, forming a triangle of figures. They are separate and yet united in the moment. In the previous pair of pictures, a fourth man waits by another lamppost at the foot of some steps, bonding the two images and composing a kind of double satori. One of the new pairings is fine, though weaker, but the other, showing a window with bars, has no obvious purpose.

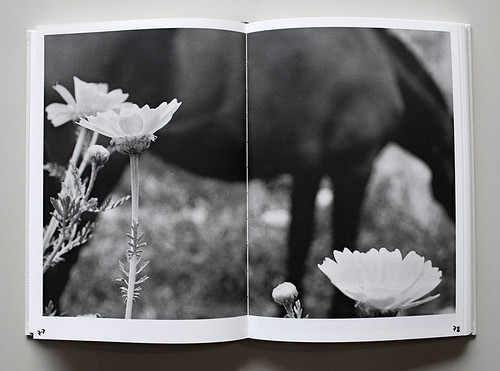

1978 (left) and 1954.

Even so, it makes sense that Thames & Hudson should publish this version of Valparaíso since it represents Larrain’s considered reassessment of the original. The volume includes most of the pictures from the first edition and its spreads are all reproduced in miniature. A handful of paintings by Larrain and letters to Henri Cartier-Bresson and Agnès Sire give further insight into a truly great photographer for whom making pictures was a form of spiritual quest.

1952.

Cover of new edition of Sergio Larrain’s Valparaíso (Thames & Hudson), with essays by Pablo Neruda and Agnès Sire.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, Professor of Design and Visual Culture, University of Reading

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.