Autumn 1994

Facing up to the reality of change

Graphic design is gripped by an identity crisis. A broader definition of the discipline would provide one way out of the current malaise

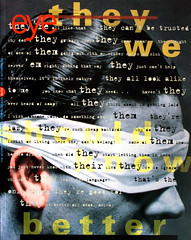

Graphic design, as it is currently practised, is an anachronism. Despite its pretensions to scholarship and professionalism, its structures and change mechanisms remain firmly rooted in it craft origins. The practice of graphic design has been dominated by Modernist notions of rational problem-solving and the search for objective, universal forms. Yet the basis of Modernism has been undermined by large-scale social change which has resulted in uncertainty about our values and a loss of consensus, both real and imagined. We live in a complex, pluralistic society. Rather than homogeneity, there are now multiple and multicultural audiences which are often in conflict. The ideals and methods of Modernism have been rejected by many of graphic design visionaries, inciting the establishment to launch attacks on the new ideas. Like a spoiled child, graphic design has not come to terms with the realities it faces.

Graphic design is undergoing a crippling identity crisis, as evidenced by the pathetic hand-wringing at design conferences and in publications such as this. Such forums have been dark places of late, full of fear and uncertainty about graphic design’s role in our brave new world. Ironically, this crisis comes at just a time when graphic design has perhaps the most to offer society. The cultural and technological changes we have witnessed in the last decade offer unprecedented opportunities for those whose responsibility it is to connect message-providers and consumers.

Graphic design’s survival as a profession may rest on its ability to redefine itself in the eyes of its publics. But what should its new definition be? Should it focus on creativity or on contributions to client success? How can graphic design gain professional respectability without selling itself short? A broader definition of the discipline as a mediator of meaning, integrating all elements of the communication process, suggests a possible way out of the current malaise.

Graphic design shares special qualities with other creative disciplines. As a result, it does not fit into traditional models of discovery and knowledge. In The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, science philosopher Thomas Kuhn outlines an idealised model for professional activity. Through ongoing research and experimentation, scientists reveal new truths which are then disseminated through the community of professionals, leading eventually to a shift in the paradigm within which professional activity takes place. Change under this model is an inexorable trek towards an immutable truth.

According to sociologist Donald Schön, professionalism is based on ‘technical rationality’, which he defines in is book Educating the Reflective Practitioner as the idea that ‘practitioners are instrumental problem-solvers who select technical means best suited to particular purposes. Rigorous professional practitioners solve well-formed problems by applying theory and technique derived from systematic, preferably scientific knowledge.’ While many graphic designers have embraced these models as ideals, neither is wholly adequate for the particularities of the profession.

The problems to be solved in real-world design practice do not present themselves as well formed, but as messy, indeterminate situations. Moreover, graphic design is holistic in that it ideally involves the integration of rigorous analysis and creative intuition. In an attempt to position itself as a professional activity, however, graphic design has emphasised analysis over intuition, minimising the importance of creativity for its own sake. An accomplice in this process has been our computer-based design, typesetting and print production tools. The marketers of these products have led their customers to believe that with the right hardware and software, they too can produce well-designed documents in no time and at a minimal cost. The value of graphic design has been diminished in the minds of many potential clients, and the profession has been unable to offer a meaningful response.

How could it, when it lacks even the most fundamental level of self-awareness? Graphic design’s professional organisations are weak; they enrich the field through their activities, but are parochial in their scope, redundant in their programming and unrepresentative of the field. It is estimated that there are as many as 250,000 professionals working in something that could be described as graphic design in the United States, yet the combined memberships of America’s three largest design organisations is less than 13,000. In the UK, there are at least 30,000 graphic designers of whom approximately 2000 are members of the leading professional body.

Graphic design lacks all but the basic mechanisms for disseminating new ideas within its professional community. Little formal analytical, descriptive or historical research is conducted, and there are few journals or other vehicles in which to make available what research does take place. Instead, new ideas are typically generated from experimentation and the development of the personal voice; they travel through the field primarily via professional publications, competitions and ultimately, style appropriation.

The trepidation underlying the current discourse about the fate of graphic design flies in the face of the new social context in which it is practised. It is as though the profession has its head in the sand. While some commentators have recognised this and challenged the profession to change, their prescriptions have lacked specificity and substance. But if we define graphic design as the mediation of meaning, we can look to several old and new sources of meaning to suggest a way out of the desert. I will suggest just a few: language, culture, complexity and technology.

Perhaps the most thoroughly developed area of graphic design research is the application of literary and language theories such as rhetoric, deconstruction, phenomenology, hermeneutics, structuralism and reception theory to visual communications. While this work has been published and debated, it is not widely understood. Scholars have long used these analytical tools, but their ideas have seldom escaped the cloistered confines of their own circles. As new and ethnically diverse audiences emerge and language changes in response to social pressures, these theories have much to offer graphic designers trying to address deep structures of meaning. In turn, designers who understand and use these tools have much to offer their clients.

Our awareness of the relationship between design and culture has been enhanced in recent years by the work of several thoughtful curators. Yet the fundamental connection between our material reality (of which the product of graphic design is such a large part) and the culture that shapes our identity has not been dealt with in professional practice except in the most superficial way: through the easy application of trendy visual forms to wholly inappropriate projects. If, as Ellen Lupton suggests, ‘There is no rigid boundary between private life and mass culture, personal memory and public record’, then the graphic design profession occupies a privileged and responsible position which it has neither recognised nor attended to.

The sciences of complexity, such as information and chaos theory, also suggest new applications for graphic design. These areas of investigation were developed to help us to understand the nature of such complex systems as language, biological organisms, ecosystems, weather, communication networks and human society. Once a system reaches a critical level of complexity, scientists have discovered, its description becomes more complicated than the system itself. Complex systems require a vast number of qualitatively distinct variables to describe their behaviour. It is hard for the human mind intuitively to grasp what is going on in such systems, but with computers the complexity can be distilled to a manageable amount of information so intuition can be applied to create an understanding of the system’s dynamics. It has been shown that some complex systems have an underlying simplicity whereby a few key variables largely determine the behaviour of the system as a whole. Such ideas can help graphic designers to communicate complex messages, help their audiences to operate complex equipment, or their clients to manage complex organisations.

Another increasingly important source of meaning is technology. The most prevalent computer-human interface paradigm, on which the Apple Macintosh and Microsoft Windows operating systems are based, was developed more than twenty years ago at the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center. Hierarchical file management systems and windows, icons and pointing devices are likely to be eclipsed by new tools and metaphors as the power of desktop computers increases. Voice recognition and synthesis, video teleconferencing, decentralised computing, wireless telecommunications, handwriting recognition, gesture recognition, media integration, intelligent agents and virtual reality all offer new possibilities. But in spite of these advances, computer science and engineering are still driving the development of computer-human interfaces, which in almost every recent case suffer from poor design.

At a recent conference in Chicago, the CEOs of several leading interactive CD-ROM publishers said that the lack of high-quality content and design is the primary factor holding back the growth of their industry. By the end of this year, it is expected that there will be more than 15 million CD-ROM drives in the US alone and that more than 3000 new CD-ROM titles will be published. This is a rapidly growing industry desperately looking to graphic design to differentiate products in a competitive marketplace.

Rather than wallow in self-pity, graphic design must embrace the new world if it is to survive. While its history is central to its identity, the models of the past are no longer adequate. Educational institutions must broaden their curricula and become centres for research and new ideas. Professional organisations must prepare their members for the future by disseminating those ideas and not let themselves be ruled by a small, established elite. And designers must engage their clients on a more substantial level and educate them about graphic design’s potential. The world has changed and graphic design, if it is not to become increasingly irrelevant, must change to keep pace.

Rob Dewey, communications director, American Center for Design, Chicago

First published in Eye no. 14 vol. 4 1994

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue.