Summer 2004

In the crazily abundant world of Martin Friedl

777 pictograms conjure up a strange new graphic universe. Critique by Rick Poynor

In classic pictograms, such as Otl Aicher’s designs for the 1972 Munich Olympics, forms are highly simplified and stylised. Aicher’s athletes are reduced to their essential outlines, their limbs arranged according to a consistent diagonal scheme. It wouldn’t be correct to call the figures solids – they are white spaces reversed out of black – but within their rudimentary forms all detail has been suppressed. This is often the case with pictograms, which more usually take the form of solid dark shapes.

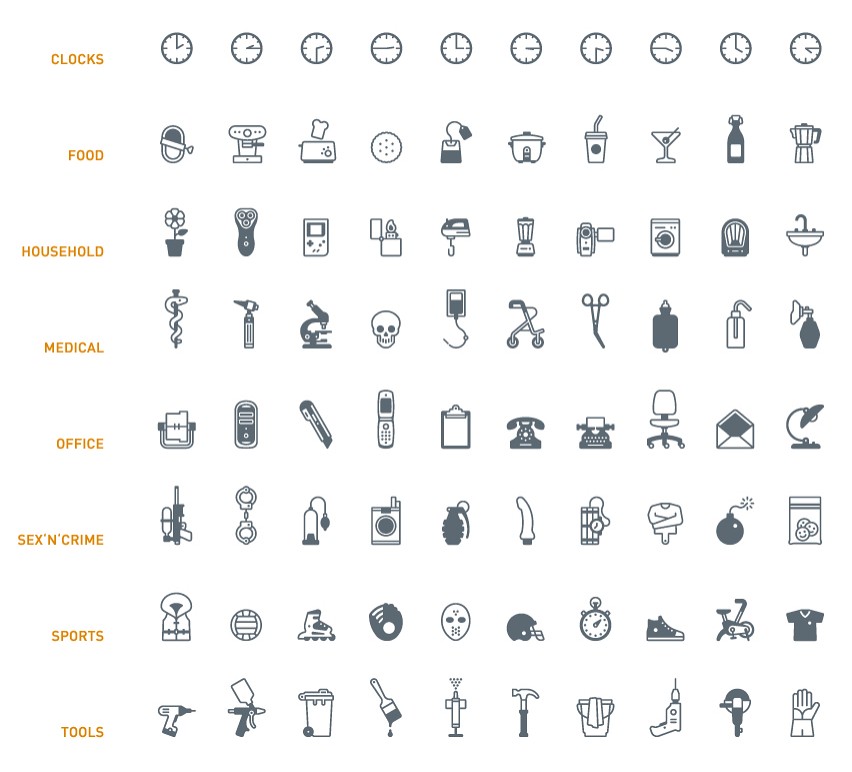

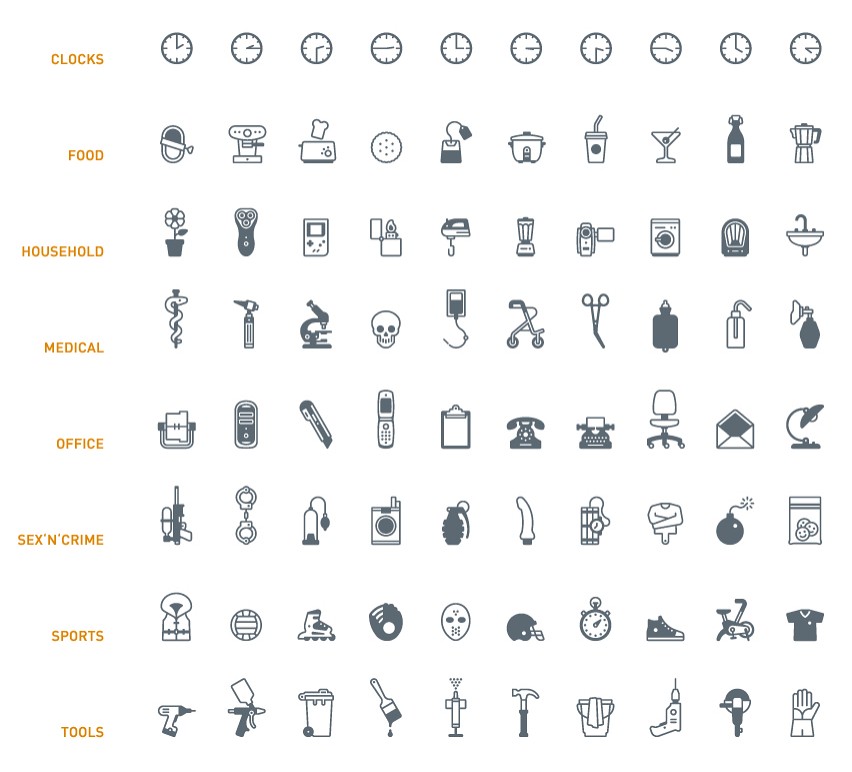

Poppi, a new collection by Martin Friedl for Emigre, is billed as a set of pictograms, but it’s immediately striking as something quite different. When I first saw the 777 symbols, presented in row after row in Emigre’s promotional booklet, the first thing that sprang to mind was the old murder mystery board game Cluedo [Clue in the US], which came with miniature metal versions of the possible murder weapons – a knife, a spanner, a gun. Poppi is so elaborate and all-encompassing that it seems less like a means of conveying specific pieces of public information than an image system for constructing complex visual narratives. One of its seven categories even covers the field of sex and crime (the others are food, household, medical, office, sports, and tools). It’s hard to imagine the everyday commercial communications that would require symbols for handcuffs, a spliff, a straitjacket, a guillotine, and an arsenal of pistols and automatic weapons.

If ordinary pictograms are generic representations, which stand for a whole class of objects, the Poppi pictograms are highly particularised. Although Friedl’s objects are all rendered in a uniform graphic style with a consistent weight of line, giving them the appearance of being a coherent system, they retain a great deal of individual character. Friedl uses solid areas not to make his pictograms block-like and ‘universal’, but to delineate objects more accurately, as in the handle of a kettle or a hammer’s rubber grip.

He also takes delight in internal details – the shape of a champagne bottle label, the toast setting on a toaster, the perforations on a sticking plaster. The images are closer in spirit to drawing than to pictograms as they are usually understood. Outline-dependent artists such as Patrick Caulfield and Julian Opie – rather than idealistic Isotype inventor Otto Neurath – seem the most appropriate reference points.

Poppi’s almost crazy sense of abundance reflects the surfeit of choices offered by consumer society. Many items, even tea bags and paper clips, come in at least two sizes. There are three styles of TV, four mobile phones, four electric drills and no fewer than six hypodermic syringes. You can have your envelope open, open with a sheet of paper, or sealed, and if none of these convey whatever you are trying to say about envelopes with sufficient precision, perhaps the address window version will do it. The wittiest moment of redundancy comes with the three piece hi-fi. The left- and right-hand speakers, though identical, are accessed separately by typing ‘a’ and ‘c’.

The aim with pictograms is often to cross language barriers and, for Modernist pioneers of the medium, this had the seriousness and conviction of a social mission. Could reading be replaced by seeing? Friedl, too, talks of his difficulties with non-Roman letterforms on a visit to Egypt and his desire to develop a ‘comprehensive image-based language encompassing all areas of everyday life’. The unusually wide range of objects he interprets recalls one of those traveller’s picture dictionaries where you point to a photograph to make yourself understood.

Poppi’s charm, though, lies in the fact that, for all its liveliness of touch, the many elements are neutral. The pictograms don’t arrive with a predetermined instructional content, or set out to warn. They have no statistical purpose and gently decline to embody anything resembling an official point of view.

The collection’s sense of openness and narrative possibility comes, above all, from the fact that it depicts not people, but the myriad things people use. Here’s a tennis racket, an old dialling telephone, a padlock, a stick of dynamite – now devise the chain of associations that will determine what these symbols, presented separately or together, might mean. Friedl’s one false note comes when he breaks from his usual descriptive realism with cartoon-like schematics of a naked man and woman showing their private parts. That can be forgiven in such an ambitious undertaking and maybe he will think better of it as he continues to convert his world into enticing little pictures.

Top: Some of the 777 Poppi pictograms, 2004. Design: Martin Friedl. Licensed and distributed by Emigre.

Rick Poynor, writer, founder of Eye, London

First published in Eye no. 52 vol. 13 2004

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.