Summer 2021

Los Angeles’ lost palace of treasures

Mark Nelson

Marcel Duchamp

Book design

Design history

Information design

Critique / Photography

Using photographic evidence, designer Mark Nelson has reconstructed one of the great twentieth-century art collections. Photo Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for Eye magazine.

Mark Nelson’s recent book, Hollywood Arensberg: Avant-Garde Collecting in Midcentury L.A., is an exceptional feat of photographic reconstruction. Co-authored with the scholars William H. Sherman and Ellen Hoobler, the project has been twelve years in the making. The idea goes back even further, to around 2005, when Nelson, who specialises in designing art books and catalogues for McCall Associates in New York, was working on his first book as co-author: Exquisite Corpse: Surrealism and the Black Dahlia Murder (2006). That volume– macabre in the extreme – introduced a researcher of great relentlessness and imagination, with the intellectual confidence to build complex arguments around fine art using visual images as an intrinsic form of evidence.

From his reading, Nelson learned about a house in Los Angeles owned by the collectors Louise and Walter Arensberg from the late 1920s to the early 1950s. 7065 Hillside Avenue was filled with a spectacular array of artworks. Nelson needed a picture for Exquisite Corpse and all he had seen were four poorly printed photographs. It seemed there was no book about the house and its collection. The arrival of Xeroxes of seventeen photos, requested from the Philadelphia Museum of Art (now home of the Arensbergs’ art collection), convinced him that he must somehow reconstruct their culture-bedecked residence. By 2008, he was ready to start digging.

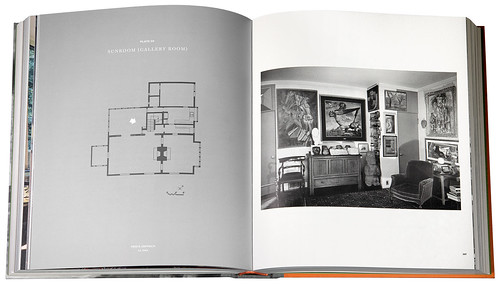

The Sunroom (Gallery Room) in the Arensbergs’ Hollywood house, photographed by Frederick R. Dapprich, ca. 1944. The white arrow indicates the photographer’s point of view, deduced from visual evidence by the book’s co-author Mark Nelson. Top. The Sunroom, photographed by Fritz Block, ca. 1942-43. Duchamp’s Glider Containing a Water Mill in Neighboring Metals, 1913-15, hangs in front of the window. Joan Miró’s Woman, 1934, can be seen on the right, low on the wall.

The Arensbergs’ huge collection consisted of three categories: modern avant-garde art, pre-Columbian sculpture and Renaissance literature. Thanks to trust funds, they were wealthy enough not to need to work. The Armory Show (1913), an international exhibition of modern art, had a life-changing impact on the couple and they began to acquire art, quickly establishing themselves as leading patrons of Marcel Duchamp, who moved into their Manhattan apartment. The artist later gave them The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even in lieu of rent for a studio.

In the Arensbergs’ Los Angeles home, acquired in 1927, their treasures, including major paintings by Cézanne, Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Klee, Miró and no fewer than 40 Duchamps, were ingeniously intermingled in displays that occupied every square inch of available space. Nelson’s mission was to uncover as much visual evidence as he could about exactly how the artworks were arranged throughout the house.

Nelson’s numbered diagram of the Sunroom, showing the fruits of his research into the Arensbergs’ collection. Alongside famous paintings such as Salvador Dalí’s Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War), 1936, and Marcel Duchamp’s Chocolate Grinder (No. 1), 1913, the display includes centuries-old masks and vessels from Mexico and Honduras.

Trawling through archives, he began to locate photos. One of his most exciting discoveries emerged from reading correspondence between the Arensbergs and Fleur Cowles, founder in 1950 of the famously lavish and short-lived Flair magazine. The portrait photographer Karl Bissinger had taken unpublished pictures of the house, and Nelson tracked them down to an unopened envelope marked only by a job number: ‘They had incredible things to tell us about rooms and artworks that we hadn’t known before then.’ Pictures of the house were, however, published in Vogue and View (both in 1945), ARTnews (1949) and the book Modern Artists in America (1951). The survey concludes with meticulous biographical notes about the house’s photographers.

After a detailed introduction seamlessly co-written by Sherman and Nelson, most of the book is given over to Nelson’s systematic visual reconstruction. Starting with the foyer, home to Brancusi sculptures and Aztec carvings, Nelson introduces each room by a floorplan, with an arrow to indicate orientation, and on the opposite page, a photograph (most are black and white) of what could be seen from that position. On the next spread, a numbered diagram, drawn by Nelson, replaces the photo and the facing page has a list of all the artists and works – there may be 25 or more – shown in the photograph. Identification was a painstaking task. A close-up of the original photograph often follows, permitting a more intimate view of key works. Using floorplans to highlight sightlines, the authors speculate about the symbolic relationships the Arensbergs established between the artworks. As the book proceeds through the house, wall by wall, across more than 250 pages, a complete panorama of the collection re-emerges with crystalline clarity from the haze of time, fully justifying Nelson and Sherman’s claim to document ‘one of the most extraordinary installations of art ever assembled in a private home.’

Cover of Hollywood Arensberg (Getty Research Institute, 2020), co-authored and designed by Mark Nelson. Marcel Duchamp sits with the couple.

Nelson is careful to position Hollywood Arensberg as a collaboration. Ellen Hoobler’s concluding essay on pre-Columbian art makes a vital contribution to a rounded understanding of the Arensbergs’ artistic interests and how the parts of their collection interrelated. Nevertheless, Nelson’s visual authorship supplies the book’s reason for being and its exemplary sense of direction. Picture research, photography, image editing and page design fuse to become both a highly engaging celebration of the collectors’ penetrating taste and an art historical investigation with the lucidity of a forensic report.

Rick Poynor writer, Eye founder, Professor of Design and Visual Culture, University of Reading

First published in Eye no. 101 vol. 26, 2021

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.