Spring 2018

Mining the ruins

When petrol replaced coal, the island of Hashima lost its purpose and slowly decayed. Rick Poynor examines a new photobook haunted by the past

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for Eye magazine.

Hashima Island, also known as Gunkanjima, or Battleship Island, has been described as a holy grail for photographers obsessed with ruins. The sixteen-acre outcrop, fifteen kilometres from Nagasaki in southern Japan, is the maritime equivalent of a coal mining village. From 1887 to 1974, when Mitsubishi, Hashima’s owner, pulled out because petrol had replaced coal as a main source of energy, miners toiled below the seabed in excavations that went down as far as 1000 metres. By 1960 around 5300 people – workers and their families – lived on the island, said to be one of the most densely populated places on Earth.

Gunkanjima’s dilapidated concrete buildings, scoured by typhoons, came to international attention in 2012, when the island featured in the James Bond film Skyfall; it can also be seen in Battle Royale II: Requiem (2003). For years, the former industrial zone was closed to visitors until, in 2009, a few safely cordoned-off areas were opened up for organised tours. Dedicated explorers who want to see the most apocalyptically ravaged and potentially dangerous sights must either seek official permission or persuade someone with a fishing boat to land them illegally when highly changeable weather conditions allow.

The Japanese photographer Makiko applied twice before she was given clearance and the British photography specialist Dewi Lewis has now published her photobook, with design and layout by Smith. Battleship Island isn’t the first survey and it is unlikely to be the last. Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre, renowned for their studies of the ruins of Detroit, published Gunkanjima in 2013. Their images of the island have a stately architectural detachment, every scintilla of decay recorded in colour with absolute fidelity. They are upmarket, gallery-ready versions of the kind of widescreen tableaux urban explorers display with pride on their websites – usually with a shot or two taken by a companion to situate themselves in the scene, ideally perched somewhere precarious.

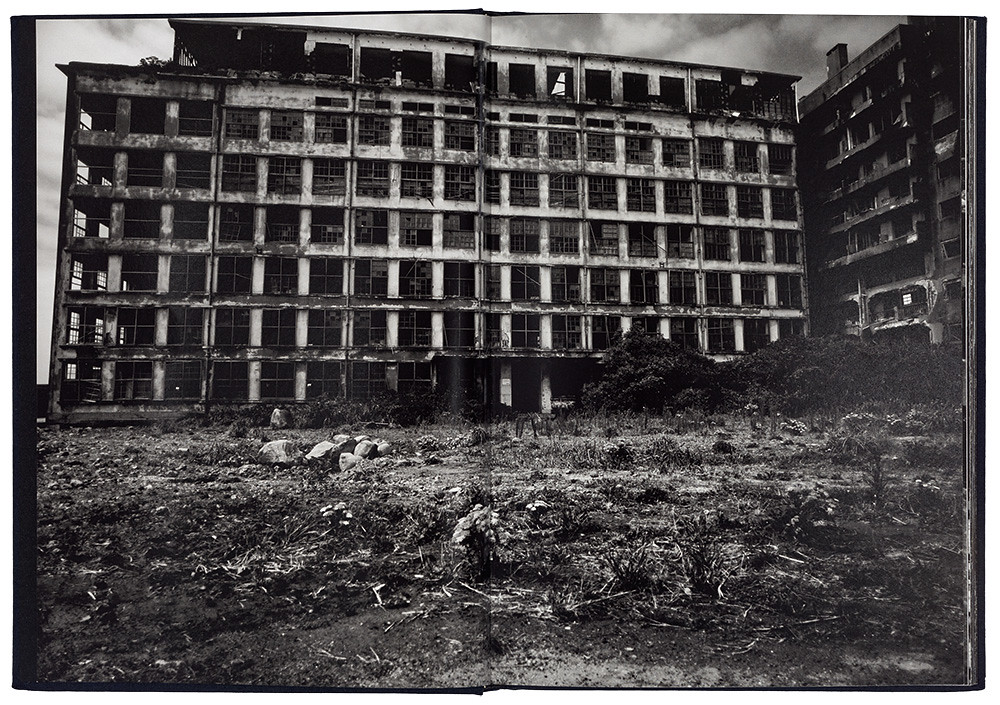

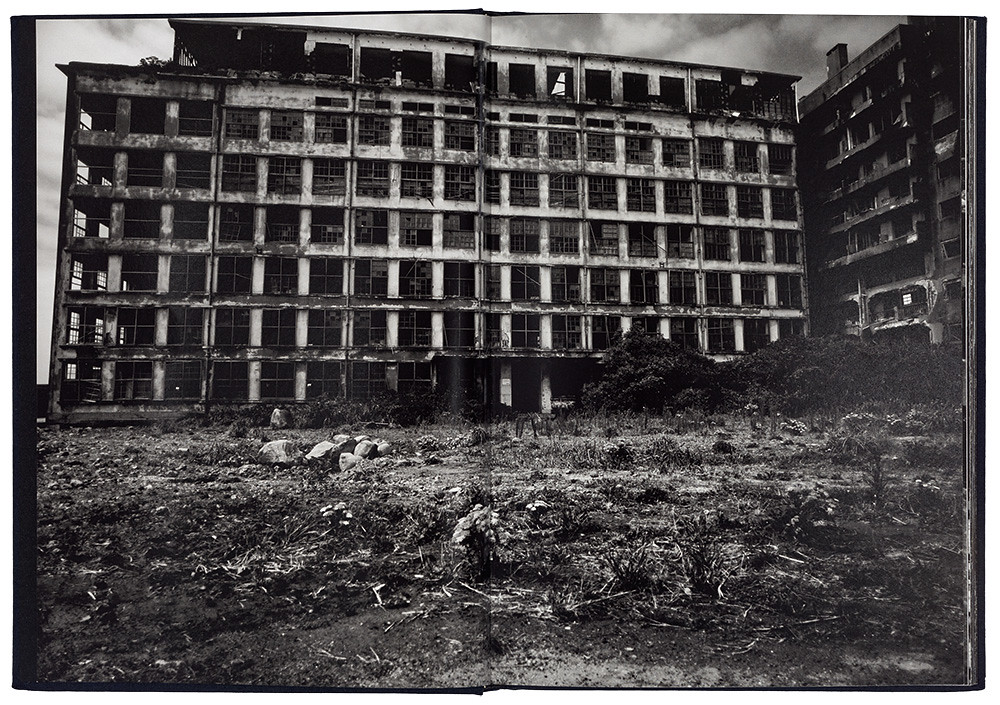

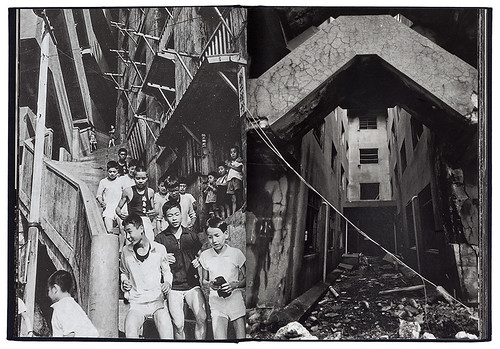

Cover and spreads from Makiko’s Battleship Island, published by Dewi Lewis, 2018.

Right: An archival picture of the ‘stairs of hell’ and a secluded space.

Top: A former school building, long abandoned.

Makiko’s pictures evince different priorities. Battleship Island looks like a classic 1960s Japanese photobook: black and white, thick with dark ink, full-bleed images on every page. Makiko isn’t interested in heroics. She doesn’t venture into the perilous buildings, even though previous photographers have documented a surprising number of possessions left behind due to lack of space on the departing boats. Makiko prefers to remain at ground level, peering up at these concrete hulks awash with rubble from a low, childlike perspective, and she avoids taking pictures of some of the most obvious landmarks, such as the so-called ‘stairs of hell’, a harsh, angular thoroughfare that ascends between the buildings.

The book’s narrative is structured to give a sense of her movements around the site. A sixteen-page sequence before the title-page progresses from long shots of façades to medium shots of smashed-in windows to a close-up of a backless chair on a debris-strewn threshold. In the following eight-page sequence, Makiko shows archival photos of children at play. The images, printed on flimsier paper, are greyer and softer and the first one returns to the building shown at the start, only this time there are people: two boys hanging out with their dogs. As these sensitive alternations of old and new images continue through the book, the former occupants come to register as ghostly presences. A girl on a swing, slightly out of focus, seems to dematerialise into the photo’s grain. Even the buildings, caught in an early photo, eventually dissolve into particles of mist.

Makiko’s Battleship Island is a Stygian, ominous place. It looks like the scene of a catastrophe, as if something malign has eaten into the fabric of the buildings, stripping out balcony railings, dermabrading walls and causing slabs of cladding to drop off and smash. The level of laceration seems to exceed what might be expected from the elements alone, and the exteriors look even more degraded in Makiko’s expressionistic pictures than they do in more purely descriptive photos. Has vandalism also played a part? Photographic intruders appear to treat the site like a shrine. In an apartment that is inaccessible to day-trippers and not shown by Makiko, a discarded TV on spindly space-age legs has been photographed where it stands several times over the years by Marchand and Meffre, and others.

Makiko’s motives for taking these pictures remain obscure. Although she says the island has haunted her for years, she makes no reference in her brief notes to its disturbing history. During the Second World War, Korean and Chinese workers, including young boys, were forced by the Japanese to work in the mines as slaves. The Battleship Island, a Korean feature film released last year, recalls (and perhaps amplifies) the episode with an enduring sense of outrage. When the island was made a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2015, the Koreans demanded that its buried history should be fully presented by the Japanese. Whatever her intentions, in Makiko’s dark pictures restless spirits still patrol these gloomy spaces.

Cover design by Smith, showing a ghostly vertical image of the island.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, Professor of Design and Visual Culture, University of Reading

First published in Eye no. 96 vol. 24, 2018

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 96 looks like at Eye Before You Buy on Vimeo.