Wednesday, 9:00am

26 June 2019

Nature in captivity

Luigi Ghirri’s rigorously composed pictures of plants outside people’s homes exercise a banal fascination. Photo Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for Eye magazine.

Luigi Ghirri (1942-92) was a surveyor before he embraced photography in 1970 and in the pictures that comprise Colazione sull’Erba – which can mean either breakfast or lunch on the grass – he undertook a close inspection of the external details of domestic life. The first photograph in both the original catalogue and Mack’s expanded publication shows the façade of a three-storey house. There are four aerials on the roof and four cypress trees form a row between the house and the grass where the photographer took up his position. A car is parked on a drive in the middle and there is nobody around. The scene looks utterly uneventful and matter of fact.

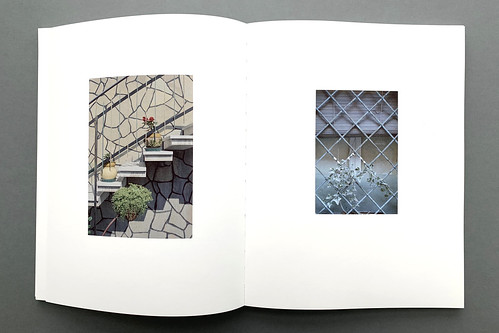

This establishing shot is the last time we see an entire building. As the general view of the house has signalled, Ghirri is interested in the relationship between man-made structures and the elements of nature – plants, bushes, trees and flowers – selected to decorate the home and, for this purpose, he favoured medium shots and close-ups. He pursued the project between 1971 and 1974 in northern Italy, but the garden adornment habit, serviced by huge garden centres, is universal and similar scenes could be found in any suburb today. The bare walls and shuttered windows, outdoor steps and garden patios, must be softened and made more amenable and habitable by shapely branches, festoons of foliage and floral displays.

All photographs: Luigi Ghirri. Image from Colazione sull’Erba (Mack, 2019). Courtesy the estate of the artist and Mack.

Although the scenes he recorded were frequently banal, the pictures are still fascinating, both as individual shots and as a set. Ghirri framed the images with great consistency. Seeking to ‘avoid formal manipulation’, he eschewed unusual viewpoints and angles and looked squarely at the subject. He rejected special lenses and filters because he wasn’t interested in optical effects and he used ordinary laboratories to develop his pictures. The lighting is uniform, largely without shadows, and the colour is subdued, even flat. ‘My aim is not to make PHOTOGRAPHS,’ he said, ‘but rather CHARTS and MAPS that might at the same time constitute photographs.’ His pictures from the 1970s – gathered in The Map and the Territory, also published by Mack Books – share a common purpose with conceptual art. Ghirri belongs to a lineage of ostensibly ‘neutral’ photographers that stretches from Walker Evans to Bernd and Hilla Becher.

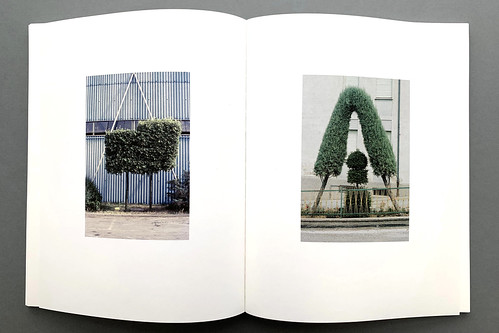

Spreads from Luigi Ghirri’s Colazione sull’Erba.

In these settings the plants look like prisoners. They are observed through railings and metal fences, where the meshes resemble the grid lines of a graph against which the unruliness of nature is being measured. They invoke the idea of botanical abundance, but the areas to which they are consigned are completely artificial and constrained. Cactuses and succulents occupy small patches of earth in decorative pots, bushes are ruthlessly trimmed into shape and the trees are lined up like soldiers on parade. A sequence of pictures shows the formalised relationships between cypresses, railings, external doors, windows and balconies; the trees have become a living element in the building’s design. The natural world is reduced to a kind of window dressing and in a number of photographs window frames do form the plants’ restrictive enclosures.

Despite Ghirri’s wish to avoid formal manipulation, the pictures have a very particular aesthetic timbre. While their unenhanced palette might suggest the randomness of the snapshot, the images are composed with meticulous attention to the disposition of every element within the frame. Occasionally Ghirri favours the stillness of symmetry; at other times he discreetly boosts visual interest by pushing an essentially symmetrical subject over to one side. Nothing that would distract from his thematic focus is allowed to intrude into the picture and this includes the homes’ inhabitants and shapers. These documents feel purified and cerebral. They filter the taste of others through the photographer’s own discriminating visual taste.

What, then, was Ghirri’s view of this phenomenon? Its ubiquity confirms a deeply ingrained need. If most of us cannot live in nature, even as we yearn for it, then we can still derive pleasure and comfort from its presence in controlled amounts in our self-made environments. Ghirri did not intend the pictures to be ironic or critical – the ‘unforgiving mode’, as he termed it. He took a detached position to try to achieve a better understanding of what he was looking at. It was not his intention to uncover and condemn an ‘impoverishment of meaning’ or ‘symbolic deprivation’ in these scenes, although his use of those words acknowledges the possibility of a negative reading. The pictures, as Ghirri hoped, remain ambiguous, their aesthetic refinement quietly at odds with their conceptual aims.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, Professor of Design and Visual Culture, University of Reading

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.