Wednesday, 11:00am

13 November 2013

Occupation hazardous

For ‘place hackers’, subversive and daredevil urban explorers, photography validates a search for the sublime. Photo Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for eyemagazine.com.

Urban exploration has been going on quietly for years, but it is only in the past decade or so that the activity has acquired a name, often abbreviated to UrbEx or UE, and taken on the loose shape of a movement.

Highly motivated, well organised devotees want to gain access to places such as industrial ruins, building sites, rooftops and tunnel systems that most people assume to be entirely off limits. In Explore Everything: Place-hacking the City (Verso), Dr Bradley L. Garrett – who bills himself equally as researcher, explorer and photographer on his website – calls this phenomenon ‘place-hacking’, drawing a direct parallel with the secretive, often illegal, activities of computer hackers.

Millennium Mills, East London

Top: Forth Bridge, Edinburgh. All photos by Bradley L. Garrett, from Explore Everything.

For urban explorers, photography is of critical importance. UE has acquired such a large international following, and become a headache for the authorities, because the explorers photograph every perilous step of their adventures and then share the pictures on the Internet. While there must be many more armchair explorers than there are active participants, these extraordinary photographs make excellent recruiting posters for those with the nerve.

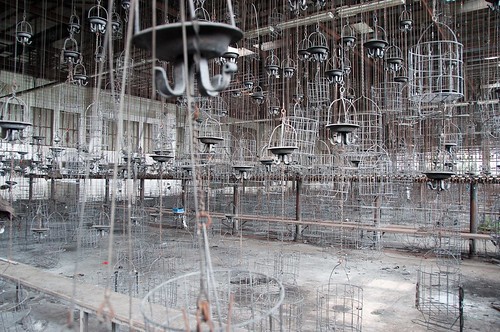

Zeche Hugo, former coal mine, Gelsenkirchen, Germany.

Garrett, now a researcher in the School of Geography at the University of Oxford, became a committed explorer to carry out his ethnographic study of the UE subculture. He began with explorations of ruins on the urban periphery, but soon progressed, as a member of a close-knit group called the London Consolidation Crew, to cracking his way into major building sites (he scaled the Shard), disused London Underground stations, the subterranean Mail Rail system, and other restricted zones.

Explore Everything mixes grippingly written firsthand accounts of urban infiltration with more reflective and theoretical passages. ‘Images embody an affective politics and are themselves a politics of possibility,’ writes Garrett. UE photographers want to astonish viewers, provoke their curiosity and make them reassess their relationship with the city. Colour pictures by Garrett and a few others, including full page bleeds and double-page spreads, punctuate the text at regular intervals, leading to a feeling of vivid immersion in the UE experience.

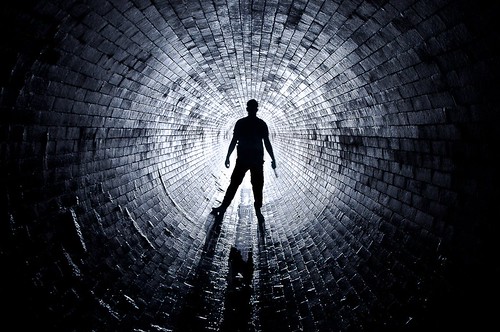

Victorian drain, London.

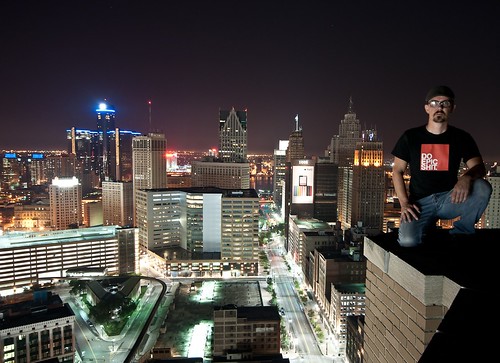

Many photos take the form of ‘hero shots’, where members of the exploration team pose, backs to the camera, gazing out over the illuminated city, or stand silhouetted in a tunnel with light streaming from behind. One of the most remarkable images, showing a hooded figure motionless atop the Forth Bridge, wraps around the hardback cover. A description of a climb across the structure of the entire railway bridge confirms the huge risks taken by urban explorers. The romantic pose inescapably recalls the lone climber looking down into the abyss in Caspar David Friedrich’s painting Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818). The urban explorer, too, can be seen as someone in search of the sublime.

The Shard, London.

UE has spawned a growing genre of photography books dedicated to hidden areas uncovered in a state of ruination. Urban explorer Julia Solis’s Stages of Decay (Prestel), published earlier this year, shows dozens of abandoned and dilapidated theatres across America. ‘No other type of building seems as fundamentally geared to dazzle the ruin aesthete as a theater,’ she writes. In Abandoned Futures: A Journey to the Posthuman World (Carpet Bombing Culture), historian and photographer Tong Lam visits sites such as the deserted Hashima Island, where coal used to be mined, off the coast of Japan – it features in the James Bond film Skyfall. ‘In this post-apocalyptic world,’ Lam proposes, ‘ruins are the forbidden playgrounds.’

Lam’s book, like Garrett’s, is captionless, relying on the reader to work out from the main text what is being shown, which isn’t always possible, leaving too many images in a state of limbo. Such vagueness doesn’t do much to counter the frequently voiced criticism that pictures of this kind are no more than ‘ruin porn’, though both Solis and Lam see these lugubrious spaces in ultimately redemptive terms. For Lam, they are places of ‘new meaning and future possibilities’ and ‘sites where creativity begins.’ Solis notes that the smaller venues, in particular, are sometimes enhanced by the deterioration, which animates them with another layer of history. Her pictures capture the buildings in a state of flux and since they were taken some of the theatres have been demolished or redeveloped. Solis provides information about this at the back.

David Broderick Tower, Detroit, Michigan.

To some, these daredevil feats of trespass will seem like unjustifiable acts of irresponsibility and sometimes also a security risk. Even to sympathisers like myself, the political motivations of some explorers often appear cloudy or contradictory. They don’t necessarily seek to change the way things are; they just want the personal freedom to ‘access all areas’. By publicising their activities and becoming notorious, they are likely to make that harder to achieve. Garrett argues with infectious passion that ‘explorers are recoding people’s normalised relationships to city space’. Yet the private transformational power of these temporary occupations of secret places surely depends on the thrill of engaging in a dangerous pursuit most people are never likely to experience. The photographs reveal there is another city, teeming with imaginative possibilities, inside the one where most of us live.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, London

Walkie-Talkie Building, London. All photos by Bradley L. Garrett, from Explore Everything.

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.