Thursday, 6:00am

27 February 2020

Scalpel sharp

A UK retrospective examines the explosive photomontages of feminist artist Linder, from the shock of her punk collages to pictures that juxtapose provocation with flowers and dance

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for Eye magazine.

Linder Sterling devised one of the most memorable images in punk, a naked woman with an iron for a head and mouths where her nipples should be. The photomontage, turned upside down, was part of a cover designed by Malcolm Garrett for the single ‘Orgasm Addict’ by the Buzzcocks. There is a credit next to the image – ‘Collage – Linder’ – but in graphic design circles there was still a tendency to think of this strikingly original creation as a work primarily by Garrett.

Not until the publication of her first monograph, Linder: Works 1976-2006, did she receive her full due for the feminist photomontages of the 1970s. Since then, Linder has created a body of coruscating images that resume where her punk provocations left off. Now in her mid-60s, she has won international recognition as a collage artist at a time when the medium is flourishing, although she prefers the term photomontage because it emphasises the use of photographic sources. Tate acquired several pieces and she had a major exhibition in 2013 at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris. Now, at last, comes ‘Linderism’ at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge (until 26 April) and the Hatton Gallery in Newcastle (from 26 September), the first wide-ranging British retrospective, which includes videos of her performance pieces, as well as specially commissioned work.

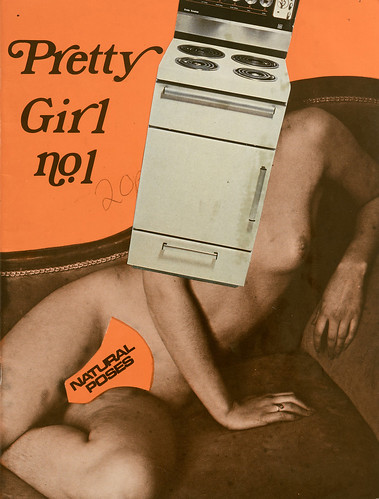

Linder, cover of Pretty Girl no.1, 1977.

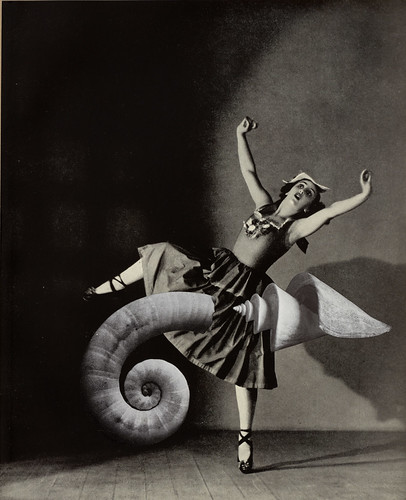

Top. Linder, Untitled, 1977.

All images © Linder Sterling.

The exhibition opens with a trenchant selection of early photomontages, though more could perhaps have been made of both The Secret Public, a fanzine collaboration with the music writer Jon Savage, and the brilliantly mordant series Pretty Girl no. 1. Here, Linder interpolates a sole colour image – camera, washing machine, record player, etc. – on to the head of the same naked woman striking 24 poses in a banal 1970s living room. The original black-and-white publication was wordless and the minimally modified pages have a steely deconstructive rigour.

What Linder showed in these works is that a single, selective, highly controlled intervention is potentially all it takes to hijack an image and redirect it somewhere its makers never intended it to go. ‘I made my early photomontages with the same curiosity as a mechanic lifting up the bonnet of a malfunctioning car,’ she told the art historian Dawn Ades, author of Photomontage (1976), which inspired Linder and a generation of budding punk monteurs. The curators, Amy Tobin and Grace Storey, exhibit a 1970s sketchbook spread with Linder’s notes on Ades’ influential survey.

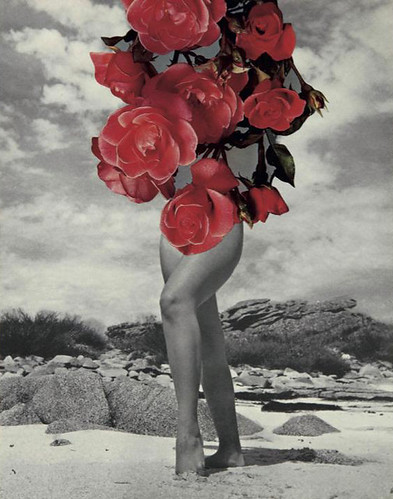

Linder, Untitled, 1977.

Linder uses the same precise scalpel cuts to achieve a seamless surface in her later montages. In the ‘Goddess’ series (2019) she pastes roses pruned from ancient copies of The Rose Annual, and other flowers, on to vintage pictures of nudes from old men’s magazines. These explosive images, mounted in a grid, are unashamedly gorgeous. They seem to propose a voluptuously inward-looking state of being, reclaiming and reinventing these one-time objects of the male gaze as avatars of private female sensation and feeling, their faces mostly hidden now behind the radiance of the petals. A wall text notes blandly that the later montages are ‘less critical’ than the early works and the overall impression of the display in this later room is unexpectedly decorous and even tasteful – a far cry from the sexual frankness and manifest disgust of punk-era Linder, seen sporting a strap-on in a video of a 1982 performance with Ludus, the band she co-founded.

The Goddess Who has Five Faces, 2019.

The Goddess Who is the Ultimate Refuge, 2019.

But ‘less critical’ is not the whole story. In the ‘Revolutionary Hardcore Formula’ series from 2010 – published in Linder (Ridinghouse, 2015) but not seen at Kettle’s Yard – slices of cake and other sugary treats mask most but not all of the pornographic details in the trashy source pictures. The intended effect appeared to be a kind of short-circuit, with a self-cancelling double helping of desire leading to queasy feelings of excess and perhaps revulsion, even though Linder never expressed it in quite those terms. Perhaps the full onslaught of her later photomontages was judged to be too near the knuckle for the gallery’s genteel audience.

If the ‘Hardcore’ series was still feminist in motivation, was it meant to be an activist demand for change, or ambiguously open? Linder also appropriates gay pornography. ‘I go into neutral gear when working with pornographic imagery,’ she says. ‘All print media is fair game, no source is excluded.’ As she works, she wonders how the women felt about being photographed, whether they are still alive and what they look like now. If they were exploited first time around in the original porn, then it is fair to ask whether they are exploited a second time by having their faces and bodies turned into art for the gallery. Maybe Linder has doubts. Tobin suggests that her participation in punk has ‘sometimes overdetermined’ the perception of her work. While the show makes valiant attempts to address this bias, Linder’s re-embrace of photomontage – at which she excels – after such a long hiatus still looks like a kind of homecoming.

Linder, Post-mortem: Irina (i), 2016.

A decade ago, in an autobiographical article for Frieze, Linder revealed that before she was five she was abused by her step-grandfather, who showed her magazines of softcore pornography. At Christmas she was given books of ballet dancers and the dancing and costumes became her antidote and solace. In some of her most affecting later photomontages, Linder recaptures the healing experience of the ballet pictures by ornamenting images of leaping dancers with the same floral blooms and sea shells that she uses to neutralise the nudes. There is a sense with all these interventions, as Linder observes, that the search for whatever she is looking for could take forever and never deliver a final answer. In a recent series, using a technique borrowed from the painter and writer Ithell Colquhoun, Linder uses enamel inks to stain the source photo by chance. In Child of the Mantic Stain (2015) – the final image in Linder – the subject is once again a naked girl.

Rick Poynor writer, Eye founder, Professor of Design and Visual Culture, University of Reading

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.