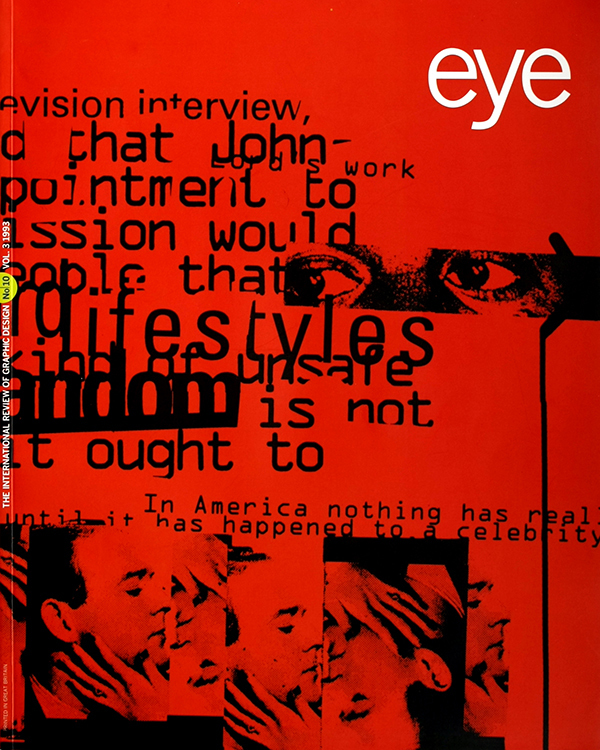

Autumn 1993

Shedding paradigms

Letter from Katherine McCoy in Eye 10

The debate about ‘ugly’ design has a decidedly nineteenth-century, crypto-Ruskinian flavour to it. Many of the quotations in Steven Heller’s ‘Cult of the ugly’ (Eye no. 9 vol.3) are from nineteenth-century sources. Come to think of it, where else does one find proponents of such paradigms? Certainly not in much twentieth-century philosophy or art.

Beauty has not been a goal of high culture in this century. Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon certainly was not about beauty, though it definitely was about rigour and quality. Duchamp’s readymades were not about beauty, though they changed the course of modern art and aesthetics. Little vernacular, pop or ‘serious’ music in this century has aspired to beauty. Chicago blues or modern jazz are more often raunchy or dissonant than ‘beautiful’, but they are also eloquent, and even refined and artful, embodying their cultures and resonating with their audiences.

So why should graphic design’s highest visual expression be defined as beauty or harmony? Certainly that is not what our clients articulate as the goal of a design project. They are interested in communcations – messages sent and received. The delivery channel, graphic design, must be cast in a form that is decidable by its audiences. Late twentieth-century audiences are our concern. The values embedded in Paul Rand’s and Heller’s paradigms are just not around much in our diverse culture today; they seem a little nostalgic and curiously out of synch.

Yet, as a faculty critic in an art school dedicated to the avant-garde, I have to admit to wishing frequently for something close to beauty as I review graduate students’ fine art. There has been an assumption among serious late-twentieth-century artists that significant work must be difficult. This is often realised as tough form and aggressive content. Perhaps you could call it ugliness. Sometimes it takes the route of banality and extreme ordinariness, as if to give viewers a shred of formal richness would sidetrack them from the higher conceptual purpose of the piece. I find myself looking in art and design for something related to beauty, but I would have to use other words.

Sensuality, visual richness and resonance come to mind. I do believe that a piece should make a contribution to the viewer. Life is plenty tough as it is, without art and graphic design making it more difficult. (Although considered provocation can be constructive, as is this debate.) And I do not believe, as do many fine artists, that richness of visual form is the enemy of content. Form can lead viewers to content, seduce them into spending the extra moments to go more deeply into the piece. (Of course, done badly, it can also stop the audience on the surface, especially if there is nothing deeper.)

Design is about life, sometimes beautiful, sometimes messy, always real. Paradigms can be artificial, rigid and exclusionary. Tina Turner’s voice ignores traditional paradigms and sets no new ones, but audiences respond to its conviction, uniqueness and personal style. The publication Output critiqued by Heller does not ‘propose alternative paradigms,’ but rather it strives to shed paradigms in favour of a particular idea, condition and audience.

Of course, one person’s beauty is another person’s trash. For some, simplicity is beautiful and complexity is ugly; for others, the opposite. A ‘Victorian beauty’, for instance, now looks overweight and out of shape. In this multicultural world (a cliché, but true) it is hard to agree on a paradigm. Should we even try? Paradigms can be hard to live up to – ask any woman as she wrestles with her hair and make-up. Some paradigms work better than others. I prefer integrity and authenticity and quality and appropriateness. But these take a little more work than simple-minded beauty.

Cranbrook Academy of Art, Michigan, USA

First published in Eye no. 10 vol. 3 1993

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.