Autumn 1992

The (layered) vision thing

Allen Hori

Katherine McCoy

David Carson

Armin Hofmann

Massimo Vignelli

Neville Brody

Design education

Graphic design

If it has dotted lines, an arrow or two and it’s impossible to read, then it must be ‘postmodern’. Are we using the theory the way it was intended?

Like acid-washed jeans and theories about Oat Bran, the word post-modernism now elicits an embarrassed – aren’t we over that? – reaction. There is a general suspicion that postmodernism is a conspiracy set loose by pretentious academics and ambitious designers inclined to overestimate the meaning of their work.

But simply to go along with such an anti-intellectual standpoint is too easy. Out of respect for post-modern thinking and its rich potential for design practice, we need to understand how certain visual conceits have come to represent the ideas of postmodern writers in design terms. From the coffee cup to rock magazines, from April Greiman to the Cranbrook Academy of Art (see Eye no. 3 vol. 1), we see a range of more-than-Modernist visual techniques that are vaguely associated with ‘postmodernism’. How have layering of type and imagery of Allen Hori’s Too Lips poster (1989), or the use of diagrammatic charts as in Katherine McCoy’s Cranbrook design poster (1989), or even the lacerated, stretched, butting columns of type of David Carson’s Ray Gun magazine come to stand for postmodernism? Are these ‘deconstructed’ graphics as McCoy has stated, ‘a visual analogue’ for post-modern theories? Would anyone who hasn’t been exposed to the language of a graduate-school design programme see this work as a ‘provocation’ to ‘construct meaning’ and ‘reconsider preconceptions’?

Postmodern theory, or more accurately the ideas embodied in post-structuralist writings, has caused a radical questioning of conventional attitudes towards the creation of art and design, and the way we interpret the meaning of the objects created. While structuralism attempted to demystify the humanist, Romantic understanding of art and literature as the mystical creation of heroes and geniuses by turning interpretation into a critical, rational science, post-structuralism tends to emphasise the instability of meaning, the limitations of objective analysis and the importance of the social and historical contexts in which the object is interpreted. Post-structuralist critics have shifted our attention away from the intentions of the designer and have critiqued the idea that a cultural product (whether a novel, a car or a typeface) has an ‘essential’ and ‘transhistorical’ meaning. Instead, they treat books, cars and typefaces as ‘texts’ which are continually filled with new meanings by the different cultures and changing historical contexts in which they exist.

For instance, a postmodern analysis of Helvetica would not centre on the ‘inherent’ qualities of the letterforms or the goals of its designer. Rather, it would analyse how those letterforms were encoded as ‘functional’ when used in the context of Armin Hofmann’s studies in Basel in the 1950s, or as ‘classy’ when used by Massimo Vignelli for the Knoll logo in the 1970s, or as ‘trendy’ when used by Neville Brody in the 1980s. By focusing on the cultural and historical frameworks of different viewers, we can see that universal or even national legibility is the unattainable. As McCoy rightly states in her introduction to the catalogue Cranbrook Design: The New Discourse, after post-modern theory, design is ‘no longer one-way statements from the designer to the receiver’.

But there is a troubling contradiction in the way Cranbrook interprets post-modern theory. A post-structuralist critique has shown that Modernism endowed visual forms with too much power – it assumed that if a typeface were made geometric, for example, it would be interpreted universally as rational, enlightening and neutral of style. Yet while Cranbrook employs post-modern theory to reveal the hollowness of such a claim, McCoy nonetheless describes certain of its own favourite visual strategies (such as decentring, manipulating type, and layering) as if they will automatically be interpreted as critically ‘self-referential’ and ‘subversive’ of our culture’s conventions. Similarly, while post-structuralist theory decentralises the agency of individuals, Cranbrook’s catalogue primarily discusses the designers’ intentions. ‘Personal content’ and ‘hidden stories’ are encouraged as a rebuttal to Modernism’s demand for objectivity. Even when they reject ‘personally generated original ‘design’ forms’ by appropriating ‘vernacular’ icons such as the Heinz logo, this is synthesised and personalised through the visual techniques of collage and layering to become the ‘high’ design of an individual.

We must remember that the majority of people who sat in a Breuer chair, looked at Paul Rand’s IBM logo, or read Vignelli’s New York subway signage interpreted that work in terms other than Modernist design theory. Is it likely, therefore, that viewers uninitiated in Cranbrook’s thinking could interpret its designers’ ‘layers of meaning’ as just one visually challenging but unmeaningful layer? While the ‘receiver’ is often discussed as an integral part of a post-modern approach, that person, their social environment and their interaction with post-modern design is rarely enlarged on.

The pioneering work of McCoy and Cranbrook has greatly broadened the design community’s acceptance of theory. I would even argue that it has changed the perception of the work of designers not involved in theory – for example, Rick Valicenti’s design has probably been both derided and given more conceptual weight due to a tendency within the design community to read diagrammatic, typographically experimental and irreverent work as the product of postmodern thinking. Yet much of the design which has loosely been called postmodern – the work of April Greiman, Dan Friedman, Robert Nakata, Allen Hori – still works largely within the confines of Modernist thinking. It concentrates on visual techniques and individual solutions rather than on cultural contexts. Much of this ‘post-modern’ design uses a visual vocabulary pioneered by the 1920s avant-garde, yet without the critique of cultural institutions that informed the found-object collages of Kurt Schwitters, the typographic havoc of the Futurists, or the socially engaged design of the Constructivists. Our attempts to go beyond Modernism are often realised by referring to visual techniques that we have been taught represent radically; avant-garde design of the 1910s and 1920s.

The influence of post-structuralist theory could radically alter not only the appearance, but the organisation, study and historicising of design. Much of the work we call postmodern lacks an analysis that goes beyond the aesthetic into the institutions that give us the tools to conceive, evaluate and produce design. Such an approach would look beyond the crop marks to analyse how schools, clients, award contests, history books and magazine articles create a value system and language which enable us to read graphic design. Such an approach would look at typefaces and visual techniques like layering not as the sole source of a design’s meaning, but within the larger support system (an article such as this, a design conference, a cocktail party) which enables us to interpret a dotted line with an arrow pointing to some scattered type over an image as ‘postmodern’.

Mike Mills, principal, Mike Mills Design

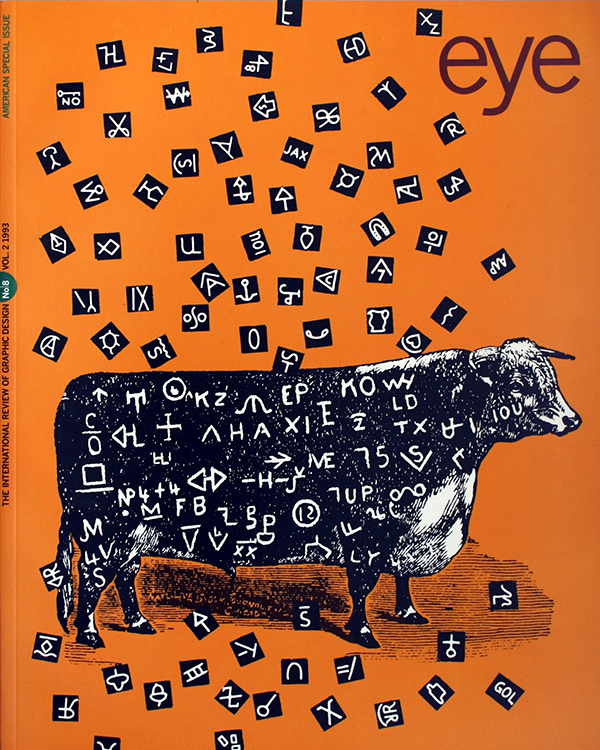

First published in Eye no. 8 vol. 2, 1993

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.