Tuesday, 12:00pm

25 September 2018

Twisting the alien

Set to minimalist techno, Arthur Jafa’s APEX is a cycle of images that illuminate the condition of black people within white-dominated culture. Photo Critique by Rick Poynor

Photo Critique by Rick Poynor, written exclusively for Eyemagazine.com

When I walked into the black American artist Arthur Jafa’s APEX, on show at Luma in Arles, I had no idea what to expect. Audiovisual work in a gallery is often an unsatisfactory experience. Viewers come and go mid-cycle, sitting on benches and getting a taste, before moving on to see the next exhibit, never finding out how the piece started or how it will end.

APEX, first shown in 2013, riveted me to the spot. It is one of the most visceral and disturbing projected works I have seen in a gallery. A ‘collage film’ in the tradition of Bruce Conner and Bill Morrison, it consists almost entirely of found still images, most of them photographs. As in Chris Marker’s similarly photographic La Jetée, cited in APEX, there is only one short sequence of movement, a black dancer swaying in the street. This appears to mark the film’s ‘start’, though it could also be the close; it is impossible to tell because APEX bites its own tail in an endless loop.

All images taken from APEX (2013) by Arthur Jafa, now showing at Luma in Arles, France until 4 November 2018.

The images filling the wall at the far end of the darkened gallery flash at you at the rate of one every 0.6 of a second – 841 of them in the course of 8 minutes and 22 seconds. The music is Robert Hood’s ‘Minus’, a masterpiece of minimalist techno that binds the listener in a rippling metal chain of sound, in a state somewhere between compulsion, exhilaration and panic. A colour-distorted image of the source album, Internal Empire (1994), is also referenced in the flow of images.

APEX is disorientating. Its atmosphere is red-hot. It feels like a contemporary version of Kino Fist’s montage of collisions in early Russian cinema. Sensation comes before meaning. Images that would repay extended reflection are instantly overwritten by the next image, making it hard at first to establish connections and decide why something is being shown. Patterns of imagery gradually emerge in dialogue with other patterns.

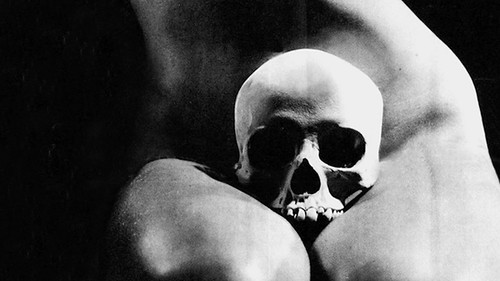

There are skulls, monstrous microorganisms and gaping mouths lined with vicious teeth. Mickey Mouse, based by Disney on blackface minstrels, appears many times – a luminescent skull has the character’s ears. Images of space craft and electronic technology recur. APEX is a kind of science fiction – Jafa sees it as a model for a ‘$100 million sci-fi epic’ – and its icons include the eye of Hal in 2001: A Space Odyssey (a huge influence for Jafa), Yoda, Gollum, H. R. Giger’s alien, a blue humanoid from Avatar, David Bowie as The Man Who Fell to Earth, and Satan from Gustave Doré’s illustrations for Paradise Lost. The pop stars seem equally ‘other’: Johnny Rotten, Yolandi Visser of Die Antwoord, Grace Jones.

Scenes of shocking violence against black people also scorch past. Jafa assembles lynching photographs, horrors from the Congo, displaced people in Africa, and a dead woman with an amputated hand rammed in her mouth, inducing a feeling of stunned disbelief. Set against these abuses are images of empowerment: Marcus Garvey, Black Power protesters, gangsta rappers, the cover of activist George Jackson’s book Blood in My Eye, as well as a gallery of black musicians, among them Robert Johnson, Billie Holiday, Nina Simone, Chuck Berry, N.W.A., the murdered rapper Tupac Shakur, and Bob Marley, smoking a spliff on the cover of Catch a Fire. In one sequence, an engraving of Nat Turner’s slave rebellion in Virginia in 1831 is followed by bleeding black bodies in a darkened space, then Miles Davis, and then a piece of tribal sculpture. From anguish to jubilation in the space of three seconds.

‘Affective proximity is a thing that happens when two things come together,’ says Jafa. ‘Certain things seek to be next to other things.’ He has constructed photobooks according to the same intuitive principle and he spent five years amassing and refining the pictures that finally morphed into APEX. With these revelatory new linkages, he aims to release the latent potential of the images, a purpose common to all forms of radical and politically motivated collage. Jafa has worked as a cinematographer for film directors Julie Dash, Spike Lee and others, and he seeks to develop a ‘black cinema with the power, beauty and alienation of black music’. These qualities are scintillatingly present in APEX, a work of Afrofuturism that lays out the historical oppression of black people, illuminates their ‘alien’ condition within a white-dominated culture, twisting the alien to become a new source of strength, and imagines a future, using the tools of science fiction, in which black potential is fully unleashed and realised.

I make this observation, though, as a white viewer and, for Jafa, the omnipresent ‘white gaze’ consistently erodes the integrity of its targets. His work, he says, is addressed to black people and aims to be a manifestation of blackness. ‘It makes available to non-black people a muscle that they don’t get to exercise enough, which is to be not spoken to all of the time.’ For a non-black viewer this perhaps gets to the nub of APEX, which is simultaneously thrilling to experience and subtly elusive to the white gaze in the visual coding of its rage.

Extract from Arthur Jafa’s APEX, 2013, shown here at the end of a conversation between Jafa and author and social activist bell hooks.

APEX is at La Grande Hall, Parc des Ateliers, Luma in Arles, France until 4 November 2018.

Rick Poynor, writer, Eye founder, Professor of Design and Visual Culture, University of Reading

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.