Spring 2002

Unclassifiable book

The New Sins consigns graphic designers to the upper levels of hell. Critique by Rick Poynor

Sin is one of those words that has all but disappeared from our everyday vocabulary. To have a concept of sin, you need to believe in an old-fashioned, fire-and-brimstone God, keeping a tally on our moral progress in this world. Yet sin, when we pause to think about it, remains a powerful idea, if only because it suggests a set of external limits and a personal accountability that we often boast of leaving behind.

So a book titled The New Sins is bound to be provocative, and this one, printed by an Icelandic maker of Bibles, comes clad in the foil-blocked,mock leather trappings of an authentic religious tract. The cover records that it has been ‘Translated out of the original tongues with the former translations diligently compared and revised’ – words taken from the King James version of the Bible. The title page attributes its wisdom to ‘The Better-Emancipated Strivers for Heaven’. Anyone encountering The New Sins stripped of the publisher’s bellyband will have to look hard to discover that its actual author is former Talking Head, photographer, film-maker, and Luaka Bop record label founder David Byrne, who created it for an art biennial in Valencia, Spain.

From his earliest songs, Byrne combined a heart-on-sleeve sincerity with postmodern irony, playfulness and ambiguity. People assumed he was poking fun at eccentric Texans in his film True Stories, but he insisted that he regarded its cast of kooks with affection. He used the strange hand gestures of evangelical preachers as the basis for a memorably weird dance routine, and his ‘new sins’ mix humour with semi-serious intent in much the same way. According to Byrne’s oddball reasoning, some of it modified from real religious texts, everything we mistakenly believe to be virtuous – charity, sense of humour, beauty, thrift, ambition, hope, intelligence/knowledge, contentment, sweetness, honesty and cleanliness – is a sin of the most insidious kind.

Byrne’s tone of religiose exhortation is impressively sustained, but it’s the nicely judged visual treatment of his questionable arguments that ultimately makes the book. The text, in English and Spanish, is illustrated by 80 of his photographs, deadpan depictions of objects, surfaces, quirky details – contentment is a plant trimmed into the shape of rabbit, ambition a swarm of ants, hell the empty corner of an office. Byrne calls the pictures ‘software programs for the eye’ and observes that the text is merely a distraction, a device to make you spend longer looking at the images.

Byrne asked Dave Eggers, editor and designer of the cult literary magazine McSweeney’s, (see Eye no. 35 vol. 9) to design The New Sins. Eggers showed him examples of Bibles in his own collection, and his page designs, each one framed by red and black box rules, have a kind of artless elegance. Headings in italic capitals and various arbitrary key words – ‘better fiction’, ‘invisible to the giver’, ‘hydraulic pipes’ – are picked out in red. Some passages have marginal notes in smaller type similar to those in early Bibles.

Where Byrne’s previous book, Your Action World, designed by Stefan Sagmeister, laboured its plasticky ironies in a way that some found too obvious, The New Sins infiltrates the mind with a subtler touch. As an object, it is small enough to carry in the pocket and dip into and to try out, as Byrne himself has done, on people who don’t know he wrote it. From his early collaborations with M&Co, Byrne has made astute use of graphic design, but that doesn’t stop him consigning designers, along with website managers and relief workers, to the upper levels of hell. ‘Their crime? Hubris. Their punishment? Equality. Everyone looks cool, fashionable and absolutely identical – well-dressed, handsome and completely boring. Everything is perfect and unbearable.’

The most appealing thing about The New Sins is the way that it resists definition. Coming from pop music, Byrne has a light touch and few have proved smarter, over the years, in using the medium as a vehicle for diverse artistic ends. You could see The New Sins as an artist’s book but, despite its weighty themes, it has none of the portentousness of the genre and it is easy to buy. It has a real subject, and many self-authored design projects look unfocused and aimless by comparison. During the Valencia biennial, it was placed in hotel rooms, like a Gideon Bible, for new sinners to discover. ‘You are floating and will seek safe harbor,’ writes Byrne. Perhaps a few bookshops will accidentally shelve it, for the faithful, among the other religious books.

Published by McSweeney’s Books, New York and Faber & Faber, London, 2001.

Rick Poynor, writer, founding editor of Eye, London

First published in Eye no. 43 vol. 11,

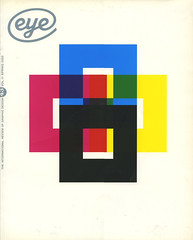

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.