Spring 2007

What do we call ourselves now?

In a world of brand specialists and information architects, is it enough to call ourselves ‘graphic designers’ without sounding either overly specialised or obsolete?

Since graphic design is not a licensed profession, we can call ourselves anything we want, with the exception of maybe doctor or Monsignor. Likewise, anyone can claim the graphic designer mantle (or ‘graphics designer’, which is a dead give-away that they’re not graphic designers) simply because they made a letterhead, newsletter or website on their home computer. So, if our nomenclature is this fungible, it stands to reason our bona fides are in question, too. A designer by any other name may still be a designer, yet what we call ourselves is key to our professional health and wellbeing. As professionals we are hired to be clarifiers, organisers and even namers for our clients. So, if we don’t know what to call ourselves, who does?

Nonetheless, given the growing intersection of graphic design with time-based media, information design and associated disciplines such as writing and producing, as well as the blurring of boundaries between fine art and design, who and what we are (and ultimately want to be) is becoming more complicated to define and, therefore, to name. Yet it wasn’t always so.

Design and designosaurs

Before W. A. Dwiggins coined the term ‘graphic design’ in a 1922 Boston newspaper article to describe the wide range of jobs he personally tackled, ‘commercial artist’ was the accepted label for the inter-related acts of drawing, spec-ing, comping and laying out. Dwiggins, however, was a jack-of-many-graphic-trades, including, but not exclusively, illustrating books; composing pages; designing typefaces (among them, Metro and Caledonia); producing calligraphic hand lettering and stencil ornament; designing books and jackets; devising advertising and journal formats, along with handbills, stationery, labels and signs; as well as writing critical essays, short stories and marionette plays. He could not have predicted that decades later his coinage, designed to distinguish his work from that of the humdrum commercial artist, would have become the standard term.

‘Does anyone here call themselves “commercial artists”?’ I recently asked an AIGA New York student conference. Predictably, not one raised their hand. But only two-thirds of them embraced the term ‘graphic designer’, and a few were rather tentative. Over a decade ago, when schools and design firms started affixing loftier titles to their degrees and business cards, the most common newbie was ‘communications design’, which, along with ‘graphic communications’ and ‘visual communications’ (viz-com), seemed to address the transition from old to new media. Later Richard Saul Wurman gave us the quixotic ‘information architect’, which, as the Web became a dominant presence in design practice, gained popularity, along with ‘user-interface designer’, ‘human-centred interface designer’, ‘experiential interface designer’ and all sorts of in-your-face interface verbiage.

Currently there is something of a schism between the curiously pejorative ‘conventional designer’, which indicates solely print-orientation, and other more artistic / technical / scientific-sounding job descriptions. The first time I heard the term ‘conventional design’ it was uttered by a guru in the Web standards movement, making a divisive distinction between Web designers and print designers, who by implication were designosaurs (try that on your business card – or website).

If graphic design is synonymous with print, and print is ‘conventional’, then a priori anything in the non-print realm is ‘unconventional’. Well, the last time I looked, print was still a vital medium in which progressive designers experiment with type and image in brilliant ways, and far too much ‘standardised’ Web design (i.e. the major news and commercial sites from Amazon to the BBC) was replete with – and at times drowning in – its own conventions. What’s more, whether on the page or screen, designers are still making graphic things.

Still, the term ‘graphic design’ is on its way to becoming obsolete. (Even the ‘MFA Designer as Author’ course at the School of Visual Arts, New York, which I co-chair, dropped the ‘graphic’ when it began, almost ten years ago, to indicate more than just print studies.) Recently, I heard a respected print designer announce the imminent end of the book – to be replaced by the ‘tablet’, which will allow pages be read like print but in pixel form – and thus the end of the book / jacket designer.

It is not inconceivable that in a few years the profession will sweep out all the old nomenclature – as it did ‘commercial art’ – for labels that alter and elevate perceptions of what we do and who we are. For instance, some of the students attending the AIGA conference told me they ‘do branding’, which incorporates graphic, Web and experiential design in one integrated package. Pressed further, they described themselves as ‘brand specialists’ – not too far from my anticipated ‘brandologists’ – eliminating both the words ‘graphic’ and ‘design’.

Back in 1993 the AIGA – founded in 1913 as the American Institute of Graphic Arts – considered renaming itself the American Institute of Graphic Design, citing a ‘dysfunctional name’ out of touch with the times and technologies. In the end, the naming committee rejected ‘Graphic’ too, fearing it would be out of date by the time the letterhead was redesigned. The name AIGA is no longer initials but a melody, with the qualifying subtitle ‘the professional association for design’ suggesting there are many sub-professions under (or perhaps replacing) the broad rubric of what was once graphic design. This makes sense in the radically integrated new media world, although, truth be known, I still like the word graphic, if only for the comfort it provides.

Identity crisis

Funnily, not all the students attending the AIGA conference knew exactly what the initials stood for. Knowing it is the ‘professional association for design’ was enough for their immediate needs. Like the organisation itself, these students face a naming (or rather branding) conundrum. How do they telegraph what they do when, for many of them, ‘graphic designer’ is too confining?

Which leads to another profound shift: the same new media causing this identity crisis are also enabling designers to do more independent, authorial or entrepreneurial work. Now all that prevents a designer, even a student, from inventing, fabricating and selling unique wares is talent, ingenuity and drive. So what do we call ourselves when the practice shifts from service-provider to producer? Maybe my own story will have some resonance.

When I first started out, 40 years ago, I called myself a cartoonist. When that went sour because my talents were limited, I became a graphic designer but really I was an art director, which is how I labelled myself for more than 35 years. Art director, by the way, is one of those jobs that even someone who is not a graphic designer can do, as long as they know how to collaborate with designers, photographers and illustrators.

A few months ago, I quit being art director. The worst part of the decision was not leaving a job I loved to broaden my horizons, but coming up with a new title to identify me. Since I had been writing articles and books, I thought I might call myself ‘graphic writer’ but that sounded almost as archaic as commercial artist. ‘Ex-art director’ was, like ‘ex-husband’, too negative. ‘Para-designer’ had a nice cadence, but lacked meaning. Since I work with students, ‘design educator’ had the right ring, but was too limiting. ‘Design impresario’ was too pretentious and ‘design consultant’ too like a non-job. ‘Interface engineer’ doesn’t quite sync with my purpose in life. And I think ‘Design slut’ is taken. So, at the time of writing I have no title, and though I still think of myself as a graphic designer, I worry that without a tag that defines me in relation to my peers and betters I will simply be a former professional. A designer by any other name is still a designer, but it is important to have a viable name, whatever it may be.

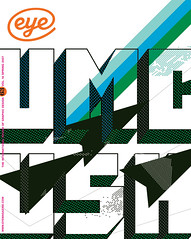

First published in Eye no. 63 vol. 16 2007

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.