Spring 2019

A century of no, No, NO

various designers

Murphy Anderson

Jack Adler

Bethany Johns

Critical path

Design history

Graphic design

Reviews

Visual culture

WE DISSENT… Design of the Women’s Movement in New York

3 October – 2 December 2018. Cooper Union, New York Reviewed by Aileen Kwun

An air of discontent has been fomenting in the US since the turmoil of the 2016 Presidential election, and notably in New York City – a metropolis teeming with contradictions.

At the end of last year a small salve to the bitter pill of current political affairs could be found at the Cooper Union, where adjunct art history professor Stéphanie Jeanjean and Alexander Tochilovsky, curator of the Herb Lubalin Study Center of Design and Typography, co-organised ‘WE DISSENT… Design of the Women’s Movement in New York’. With a selection of roughly 250 prints, publications, posters, artworks and ephemera, the exhibition framed the city’s powerful social history of women’s activism through the lens and medium of graphic design and visual art.

The Cooper Union’s progressive legacy made it an appropriate location for the show, which was installed in a modest basement-level space of the school’s dramatic academic building – a hulking steel and ruptured-façade structure designed by Morphosis in 2009.

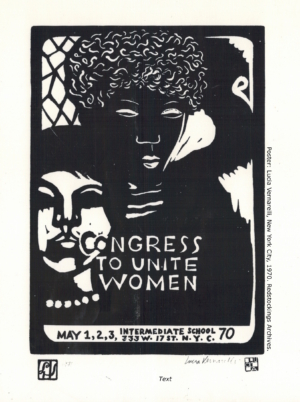

Lucia Vernarelli, ‘Congress to Unite Women’, New York City, 1970. Courtesy Redstockings Archives and Special Collections.

Top: ‘No Means NO’, from Women’s Action Coalition (WAC) Blue Dot series, 1992, designed by Bethany Johns.

Several works on display predated the 1920 ratification of the US Constitution that granted women the right to vote – including a charter for the foundation of the New York School of Design for Women, which opened in 1852 and was integrated into the Cooper Union when it opened in 1859 as a free tuition institution for all genders and people of colour. As The New York Times wrote in 1860: ‘Every effort to open new avenues of honorable personal independence to women is a duty done to society and to civilization.’ Subsequent exhibits demonstrated how the arts became a mode of empowerment for the women’s movement.

A 1914 handbill headed ‘What is Feminism?’ advertised a series of ‘Feminist mass meetings’ at the People’s Institute at Cooper Union, citing a list of women’s rights. These include the right to work; to be mother of one’s own profession; to her convictions; to her name; to organise; to ignore fashion; and to specialise in home industries. Purely typographic, typeset and designed with the urgency of a newspaper, these early printmaking works demonstrate the freedom of the press in visceral, moving ways – something that is easy to forget in the ease and inundation of information in an era run on social media.

Nearly half of the works on display, Tochilovsky noted, drew from the Lubalin Center, while many others were brought in as loans from nearby archives. Highlights included ephemera from the 1960s Women’s Liberation Movement and the National Organization for Women (NOW), made with a spirited DIY ethos.

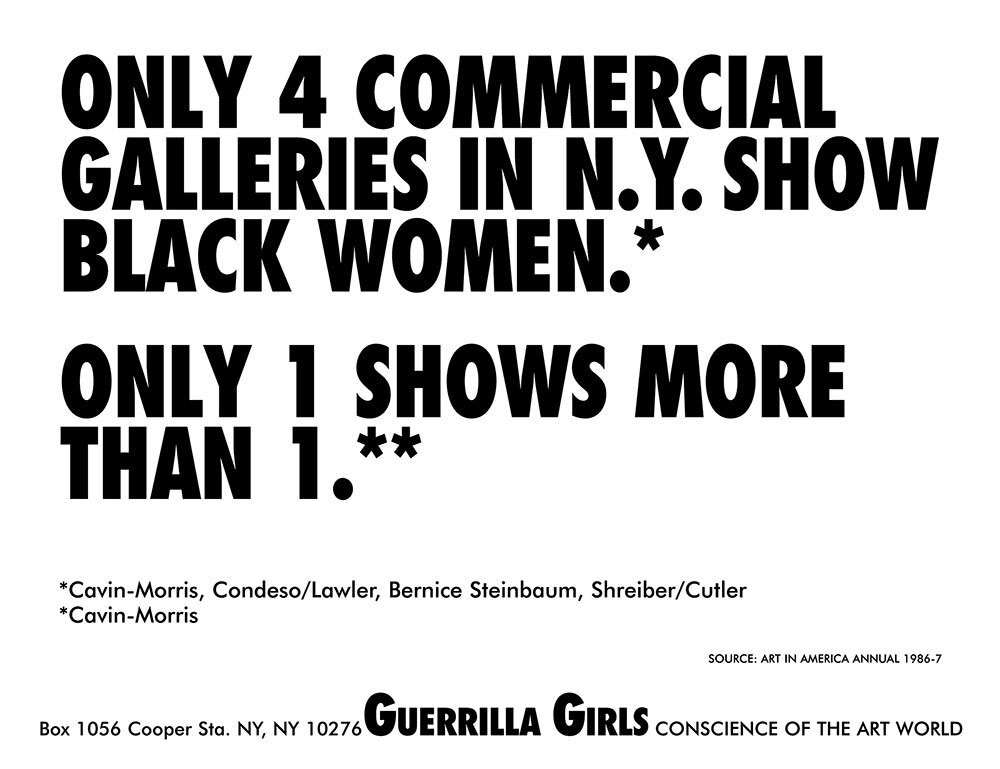

Guerrilla Girls, ‘Only 4 Commercial Galleries in NY Show Black Women’, 1986. Courtesy guerrillagirls.com.

Other works, such as those by the Guerrilla Girls, the anonymous 1980s art collective, employ the visual language of commercial advertising to fight sexism and racism embedded within arts institutions, with wheat-pasted posters, books, billboards, and other public ‘culture jamming’ tools that have since been elevated and co-opted by museums across the world. Familiar works by New York artists Barbara Kruger (Eye 5) and Laurie Anderson (Eye 76) also figured in the show, as its scope widened to demonstrate how the women’s movement became a wider coalition for women of colour, the LGBTQ community, HIV patients, Native Americans and other marginalised groups. ‘In short, feminism is humanism,’ as Jeanjean put it.

At the centre of the gallery space was a reading room and sizeable library of dozens of books, all seminal and diverse expressions of thought, ranging from Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, to Valerie Solanas’ S.C.U.M. Manifesto (Society for Cutting Up Men) and a first-edition paperback copy of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, the dystopian 1985 novel depicting a totalitarian state set against women, now a hit TV adaptation. All this, amid a real-life backdrop of intensifying gender and identity politics, and a new wave of feminism whose battle cry has coalesced, in large part, by the empowering but heartbreaking #MeToo movement against sexual violence.

More contemporary (and uplifting) publications on view included No Man’s Land, the biannual magazine launched in 2017 by The Wing, a women’s only co-working space with five locations plus six to come. Pentagram partner Emily Oberman, who designed the magazine pro bono, references seminal feminist publications such as Ms., Spare Rib and Bitch that helped pave the way.

Cover of Ms. magazine, July 1972 by Murphy Anderson and Jack Adler.

Providing a brief graphic history to the country’s waves of feminist activism through the generations, the show was a tool of empowerment in itself, and some source of comfort in an era of profoundly distressing political instability and shameless controversy. ‘WE DISSENT …’ opened just a few days before Brett Kavanaugh was confirmed as a justice to the US Supreme Court, in spite of facing sexual assault accusations from multiple women, and a gut-wrenching testimony from Christine Blasey Ford.

Co-curator Jeanjean said that such resonances could not have been anticipated when they began planning the show in 2016, but that they attest to the ‘profound and still too often unspoken gender tensions and discriminations’ in society. She pointed to works that reference Anita Hill, who in 1991 testified an account of sexual harassment against Clarence Thomas in his Supreme Court confirmation hearings.

‘History repeats itself and has proved again that women’s claims are most likely to be simply dismissed,’ said Jeanjean. ‘This reinforces the necessity for a strong and long-lasting #MeToo movement, which unfortunately does not target a new issue but finally exposes old practices.’ For viewers of a younger generation – this writer included – the exhibition provided welcome grounding for making some sense of an increasingly complex society.

Design for dissent has roots and a history, as this show reminds us – it is a living mechanism for social progress, and a viable future only, as each successive work urges, if you do the work to press it forward and cultivate the collective garden. As one of the show’s many forceful dictums by Jenny Holzer beseeches: ‘Action will bring the evidence to your doorstep.’

Aileen Kwun, writer and editor, New Year

First published in Eye no. 98 vol. 25, 2019

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 98 looks like at Eye Before You Buy on Vimeo.