Winter 2014

A man of high purpose

Designing the 20th Century: Life and Work of Abram Games

Jewish Museum, London NW1 7NB<br> 8 September 2014–18 January 2015<br>

Drawn from the magnificent archive of the artist’s family, this engaging centenary exhibition explores the life and work of Abram Games (1914-96), a pioneer of twentieth-century graphic design. Unpublished and preparatory work is displayed alongside celebrated designs of extraordinary visual power, giving an insight into the artist’s practice and profession.

Games was the son of Jewish immigrant parents from Eastern Europe. His father, Joseph, was a photographer who taught him the art of colouring by airbrush. Games said of himself: ‘I feel intensely Jewish and I think it has contributed to the character of my work.’ This is a personal story, traced through family portraits, delightful handmade greeting cards, letters and photographs, and a recreation of his studio – complete with easel, tools, equipment and the artist’s smock.

Professionally, Games was a bit of a rebel, though all in the cause of artistic excellence. After being dismissed by his headmaster at Hackney Downs School with the words: ‘To be an artist you need talent, and you haven’t got it’, then dropping out of Saint Martin’s School of Art after two terms, he decided to teach himself. By day he worked as his father’s assistant; by night he built up his own portfolio of poster designs.

Games was influenced by Edward McKnight Kauffer, an American-born artist whose Modernist style of visual communication helped to inspire Games’s own aesthetic of ‘Maximum meaning, minimum means’. He also acknowledged his debt to the great French poster artists Jean Carlu, Paul Colin and A. M. Cassandre, and to other exponents of Continental practice, such as the German Ludwig Hohlwein, whose style integrated text and image into powerfully unified designs. Games would have been aware of their work through design periodicals such as Modern Publicity.

From 1932 to 1936 Games was employed by the commercial art agency Askew Younge, where he made use of his airbrush skills. Meanwhile he set about building up an impressive independent portfolio of clients, which included such enlightened patrons of the poster as London Underground, the GPO and Shell. An article – ‘Fitting posters to the product’ in Art and Industry, August 1937 – helped establish his reputation.

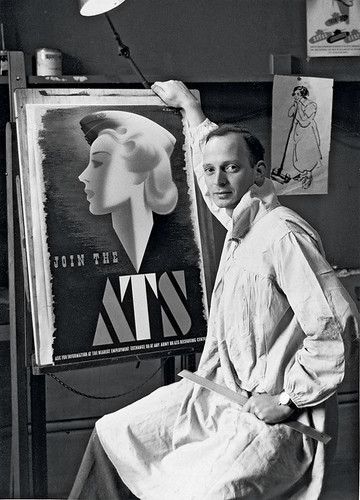

The Second World War dramatically shaped Games’s career. He joined the infantry, then in 1941 (having criticised the banality of army information posters) was moved overnight to the War Office’s public relations department. Here he produced celebrated – and sometimes controversial – work. In a recruitment poster for the Auxiliary Territorial Service, ‘Join the ATS’, he chose an alluring beauty as his model, triggering a newspaper sensation and debate in Parliament about the ‘Blonde Bombshell’, whose glamour was seen by some as counter-productive to patriotic recruitment. It was later replaced by a less seductive image.

Illusionistic posters with the slogan ‘Your Britain, Fight for It Now’ (1942), for the Army Bureau of Current Affairs, showed his familiarity with European Surrealists, such as Salvador Dali and Giorgio de Chirico. The starkness of one image, contrasting the idealistic architecture of the Finsbury Health Centre with a ruined slum dwelling containing a child with rickets and the scrawled word ‘disease’, incurred the wrath of Churchill, who had the poster withdrawn.

Games was inspired by ethical causes, believing that the high purpose of many wartime posters was crucial to their excellence. In ‘Your Talk May Kill Your Comrades’ (1942), three soldiers are bayoneted on a spiral of careless gossip, requiring the viewer to make the connection between cause and disastrous consequence. Games used photography sparingly, but here to dramatic, almost cinematic, effect.

The postwar period was hugely successful for Games. He designed a stamp for the London 1948 Olympics – earning himself the nickname ‘Olympic Games’ – and created the emblem for the Festival of Britain (1951). He also conceived the first BBC moving ident (1953), an emblem with an all-seeing eye surrounded by flashing ‘wings’, for which preliminary drawings are displayed. Games was one of a group of artists in Britain, including F. H. K. Henrion, Hans Schleger, Tom Eckersley and George Him, who were seen as mid-century Moderns.

In the 1950s and 60s Games was commissioned by many commercial clients, as illustrated by witty posters designed for London Transport, Guinness, Gestetner, BOAC, the Orient Line, The Times and Financial Times. He also remained committed to design as a force for social good, as his ‘Freedom from Hunger’ (1960) poster for the United Nations reminds us.

But the times were changing. With the advent of television, and a shift from the individual freelance designer to corporate advertising practice, hand-drawn illustrative work was in less demand than photography. While adapting happily to technical advances in colour printing, Games retained his fierce belief in the individuality of the graphic designer. As the exhibition makes clear, it is his self-belief, his sense of artistic and social purpose matched by sheer accomplishment, that gives his work its international significance.

Games in his War Office studio, with his ‘Join the ATS’ poster, July 1941 © Estate of Abram Games.

Top: ‘Your talk may kill your comrades’. Poster by Abram Games, 1942 © Estate of Abram Games.

Margaret Timmers, consultant curator, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

First published in Eye no. 89 vol. 23 2014

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions, back issues and single copies of the latest issue. You can see what Eye 89 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.