Summer 2016

A message for modernity

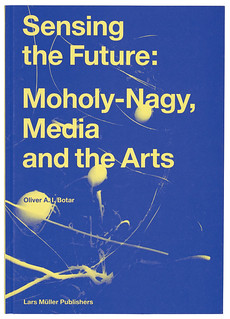

Sensing the Future: Moholy-Nagy, Media and the Arts

By Oliver A. I. Botar<br> Designed by Integral Lars Müller<br> Plug In Institute of Contemporary Art, Bauhaus-Archiv / Museum für Gestaltung, Berlin. Lars Müller Publishers, €35<br>

In the late 1950s I had tea in London with László Moholy-Nagy’s former secretary, surrounded by his paintings and sitting on slippery plywood prototypes of chairs by Charles Eames, who had studied with Moholy-Nagy. In conversation we came to link the chairs with the plywood splints that Eames designed for injured servicemen in the Second World War with the wooden ‘Hand Sculptures’ made at the School of Design in Chicago. And we asked if it was possible to imagine Eames’s films without his teacher’s example. Each generation will have its debt to Moholy-Nagy.

‘The person, not the product, is the end in view.’ Moholy-Nagy’s maxim was a motto for many British graphic designers trained in the 1950s. They had been born in the few years when Moholy-Nagy had been working in London, designing exhibitions, window displays, posters for London Underground and working as a photographer and film-maker.

Many of that generation (I was among them) were educated by his books The New Vision and the compendious Vision in Motion, published in 1947, the year after his death. Nearly 70 years on, Moholy-Nagy’s personal vision remains persuasive, and is the focus of this book, the catalogue of an exhibition staged recently in Canada and in Germany.

‘Mapping Moholy-Nagy’s achievements on to the matrix of twentieth-century art, media art, cinema, alternative education and media theory’ is the task Botar – author of a previous study of his early life – set himself, and he leads the reader along many paths of Moholy-Nagy’s thinking.

The book contains many images, several previously unpublished: photographs of the artist and his associates, Moholy-Nagy as a teacher, reproductions of his paintings and collages, pages from his books, typographic designs, book jackets, exhibition and theatre designs, film stills, and experiments with photography. Not only does this work fit Moholy-Nagy comfortably into histories of graphic design, but there is an important place for his theoretical contributions, in particular his notion of ‘typofoto’ and his Bauhaus Book, Malerei, Photographie, Film [Painting, Photography, Film], published in 1925. Botar quotes to great effect from Moholy-Nagy’s writings and makes clear that his lasting influence has been less on account of his creative activity and more because of a set of attitudes to new technologies of communication and their effect. This was recognised by many commentators on mass media, first by Marshall McLuhan, who later elaborated such views in The Medium is the Massage. This book goes further in relating Moholy-Nagy’s teaching to the digital world.

Moholy-Nagy’s more general writings have lost none of their sharpness. ‘At present’, he wrote in 1934, ‘our education is an overwhelmingly intellectual one, ignoring almost everything to do with our sensory experiences.’ And sensory experience was at the centre of his teaching at the Bauhaus and the Institute of Design in Chicago. Botar points to Moholy-Nagy’s concern that education provided no preparation for modernity and the saturation of the senses from the sounds and images of mass communication. Much of his work, as a teacher and artist, sought to remedy this. His goal was simple: an ‘organic way of life’.

Sensory training included taking control of new media, expressed in the concept ‘from reproduction to production’. One example was his recommendation to play with photographic equipment and, with no preconceptions, see what images it would produce. Moholy-Nagy’s own photographs became divorced from optical reality, almost unrecognisable in their eccentric angles and distortion, or their printing as negatives. He was a pioneer of the photogram – ‘camera-less’ photographs made with photographic paper – producing effects of light and transparency that fascinated him, suggesting infinities of depth unobtainable in painting. Photography led to film, sound and music, and to the making of his ‘light machines’, which were the source of almost limitless compositions formed by projecting light through the structure on to a wall.

There have been several monographs on Moholy-Nagy. In Botar’s case, the thematic rather than chronological arrangement makes it difficult to follow the development of Moholy-Nagy’s thinking. But when a book is so rich in content and so admirably argued, this hardly detracts from its value. Sensing the Future is a collaboration between the Bauhaus-Archiv / Museum für Gestaltung, Berlin and the Plug In Institute of Contemporary Art, Winnipeg, and was initiated to commemorate an exhibition at the Institute combining works by Moholy-Nagy with commissions from contemporary artists which embody aspects of his aesthetic concerns. The illustrations of these artworks form only an appendix to the main study.

Apart from the position of some captions – difficult to relate to the image – and the absence of an index, the editing, design, printing and binding of the book are exemplary. It even includes a facsimile reprint of Telehor (a single-issue journal from 1936 devoted to Moholy-Nagy which contains some of his most important texts), with English translations.

Oliver Botar has prolonged the afterlife of this master of the avant-garde. To have done so with the clarity provided by meticulous scholarship is a rare achievement in design history.

Cover shows a recoloured detail of an untitled photogram, 1940.

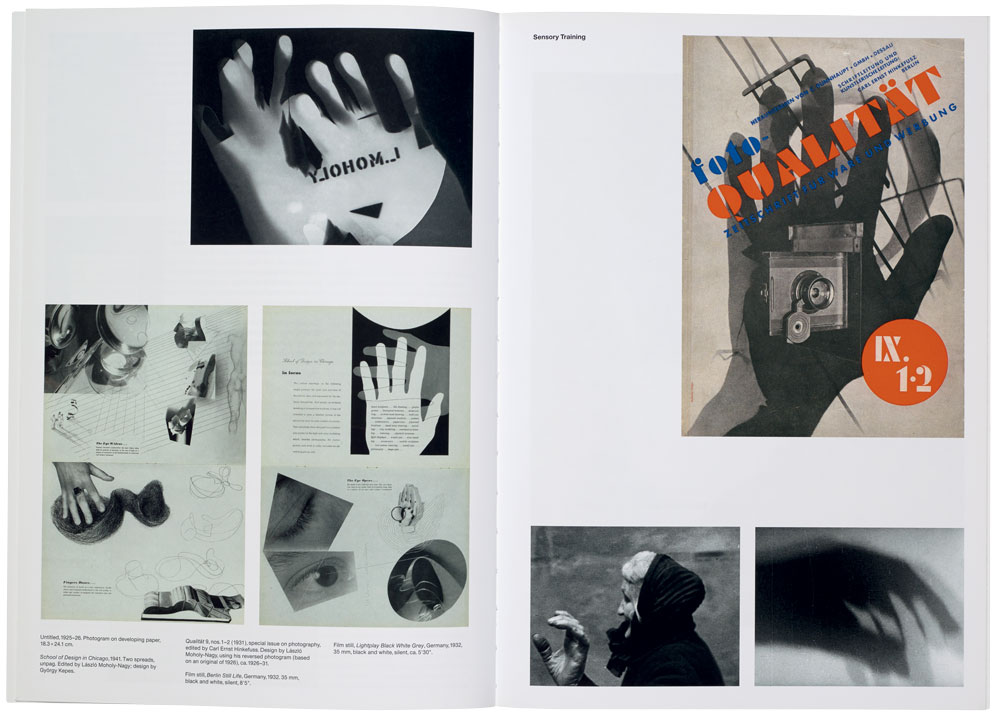

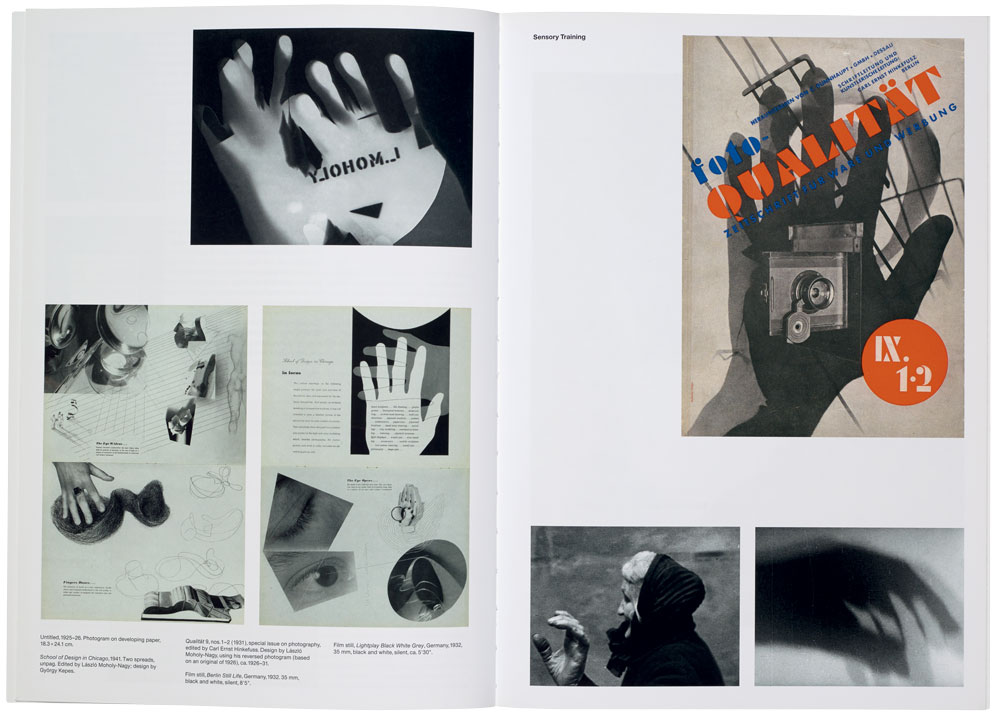

Top: Spread from Sensing the Future. The layout includes a photogram, 1925-26; two vertical spreads from School of Design in Chicago, 1941; cover of Qualität, nos.1 & 2, 1931; and film stills, 1932, Berlin Still Life, and Lightplay Black White Grey.

Richard Hollis designer, writer, London

First published in Eye no. 92 vol. 23, 2016

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 92 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.