Winter 2017

A social process

Richard Hollis Designs for the Whitechapel

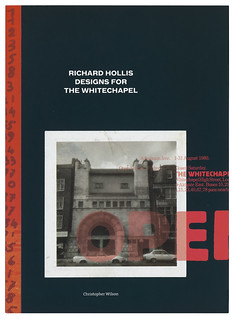

By Christopher Wilson<br> Designed by Christopher Wilson<br> Hyphen Press, £30<br>

Despite a long and eclectic career that variously spans design, printing, teaching, history and writing, Richard Hollis remains something of a cult figure. His design for John Berger’s influential book Ways of Seeing (1972) remains an important item in the design canon, although to Hollis it was just ‘another job’ among many – his design service, he says, ‘was a job. Like plumbing.’ Hollis, who spent the vast majority of his career working solo from a home studio, has been both prolific and averse to self-promotion.

Ways of Seeing may stand out as one of Hollis’s most well known jobs, but getting a good look at the rest of his output has been more difficult. Occasional Papers anthologised Hollis’s writing (including several articles and reviews first published in Eye) in About Graphic Design (2012), and his Graphic Design: A Concise History (1994) and Swiss Graphic Design (2006) are significant texts of design history. Happily, the absence of a title dedicated to Hollis’s own work has now been remedied with the publication of Christopher Wilson’s Richard Hollis Designs for the Whitechapel.

Although it features a thorough biography of Hollis’s early years, and reproductions of much of his work (Hollis’s mistakes and regrets feature, as well as his successes), this dense 400-page book is far from the conventional monograph or coffee-table celebration. Nor would a more superficial book be appropriate in the first place, something that Wilson, who worked with Hollis from 1999 to 2003, signposts from the beginning. He tells us that Hollis, ever against pretences and ostentation, always pushes conversations ‘away from himself’, so that in a chat with Hollis ‘even the tangents have tangents’.

Wilson, who interviewed Hollis for Reputations in Eye 59, captures the nuances of Hollis’s personality and work, and the minutiae of his methods, through discussion of his practical techniques, rigorous approach, philosophy, personal life and how much he charged (or, as pointed out, ‘undercharged’) for projects. The depth of Wilson’s research shines through, especially in the extensive interviews with the man himself and those who have considered Hollis a friend, colleague, acquaintance or teacher over the decades. The roll-call of names referenced throughout the book reads like a Who’s Who of the British art and design world of the latter half of the twentieth century.

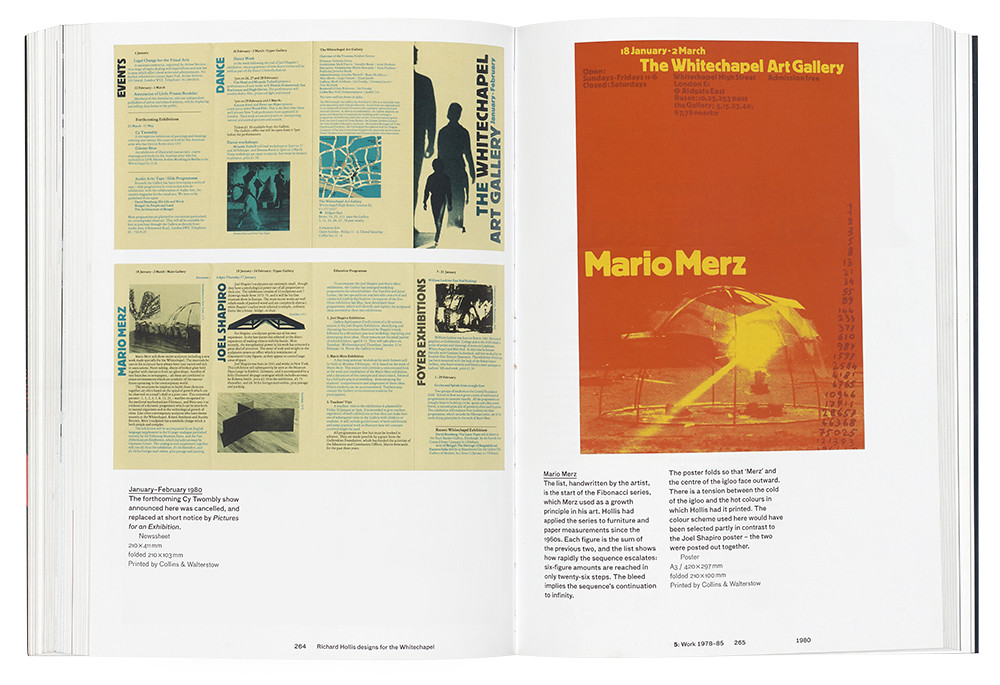

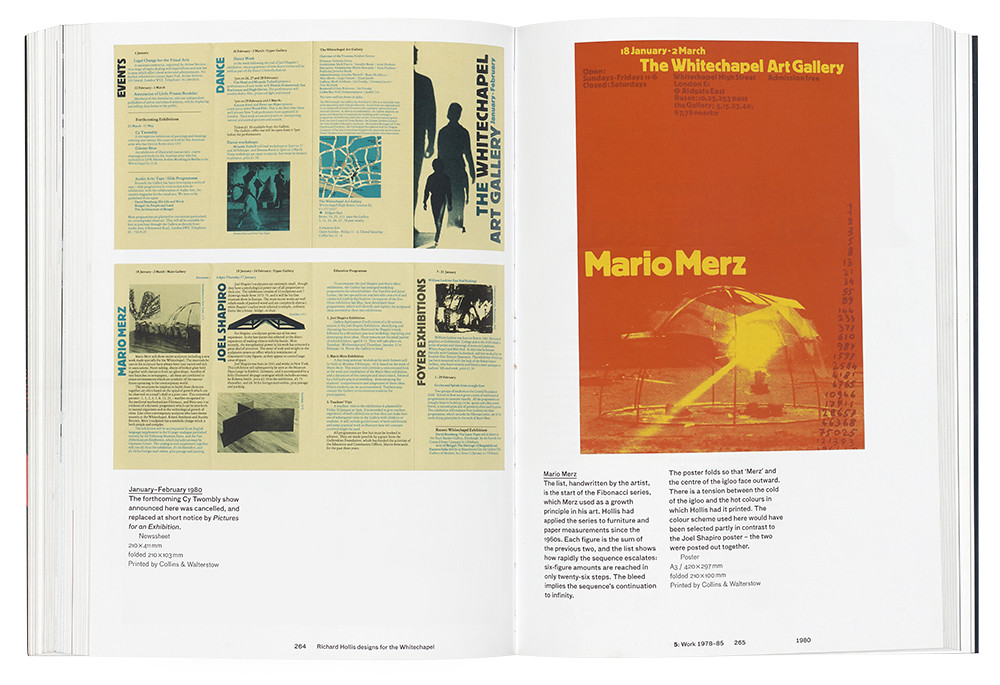

Spreads and cover from Richard Hollis Designs for the Whitechapel (Hyphen Press), designed by its author, Christopher Wilson.

This is not a book about Hollis alone. Wilson’s method – focusing on Hollis’s work for one client – becomes a lens through which a story can be told with a richness not usually found in books on design. The book has two protagonists (and consequently double the stories), the second being the Whitechapel Gallery itself, which has also lacked a book dedicated to its history.

The similarities between designer and client continue. In the Whitechapel Gallery, with its benevolent, democratic origins, a small staff and tight budgets, Hollis found a client for whom his work, with its focus on economy and getting the most out of the least, was ideally suited. The close collaborative method that Hollis favoured blossomed with the Gallery’s directors, resulting in many late nights working together in his home studio – an illustration of the Hollis idea of design as a ‘social practice’.

Hollis, who saw his role as like a ‘doctor’ treating a ‘patient’, solved the Gallery’s myriad visual problems on shoestring budgets, a job that required all his inventiveness, resourcefulness and print expertise. Here the book often delves into an arcane world of folds and print formats, with explanations of now obsolete graphic techniques plus a helpful technical glossary. As well as being an in-depth exploration of the working relationship and story between designer and client, the book’s span and complexity means that it also functions as a potted social history of postwar Britain, showing the changes that occurred in the country’s politics, culture, design industry and art world.

Structurally, having introduced Hollis and the Whitechapel individually, the book unfolds in chronological order. The main sections cover the first four years (1969-73) in which Hollis worked for the Whitechapel, an ‘Interregnum’ when they parted ways, and the second era, starting in 1978, when he was rehired by new director Nicholas Serota, who would later run Tate for 29 years.

These major sections are split in two, with a long explanatory text followed by a showcase of Whitechapel design work, both in chronological order. This can result in a lot of flipping backwards and forwards to see what is being discussed and described. The more text-heavy sections feature integrated images, often in narrow columns on the pages’ outer edges – a Hollis-like touch, but one that means the pictures’ details can be hard to make out. But the design work for the Whitechapel itself is always shown at a decent size with comprehensive captions. Aspects of the designs are often shown at their true scale, which proves important given Hollis’s exacting working methods.

The short final section covers the Whitechapel once it was re-opened in 1985, after a makeover and the addition of a new wing. This new ‘Whitechapel’ dropped the ‘the’ and swapped Hollis for Peter Saville Associates. This change, which perfectly illustrates a larger shift in British design and culture, is dealt with in a few pages. After following the intertwined histories of both Gallery and design in such depth, you might want the stories of both to go right up to the present day. But in not doing so the book retains its sharp focus. Wilson has told a fascinating and illuminating story.

Theo Inglis, writer and designer, London

First published in Eye no. 95 vol. 24, 2018

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 95 looks like at Eye Before You Buy on Vimeo.