Summer 2006

A very English tradition

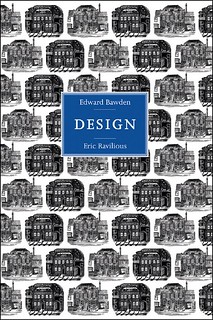

Design: Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious

By Brian Webb and Peyton Skipworth<br>Antique Collectors’ Club, £12.50<br>

If graphic design history can be read as a family tree, Britain has long played the role of the unexceptional distant relative. For many years we were faintly conscious of their achievements, but, when contrasted to their more illustrious European and American cousins, these worthy endeavours never seemed to merit any great critical attention. Fortunately, with the arrival of books on Abram Games, Edward McKnight Kauffer (admittedly an American, but one we appear to have adopted for ourselves) and Ashley Havinden, this inaccurate design genealogy is slowly being revised.

One thing still common to many of these early biographies is the wish to live up to the triumphs of our European relations by focusing upon the proponents of Modernist design in Britain. Admittedly, this trend stems from the understandable need to acknowledge how British designers have played an important role in the development of a forward-looking design language. Yet, just as the history of Swiss graphic design has become synonymous with a very specific constructive aesthetic – one that has served to overshadow our awareness of the equally influential, but little discussed, illustrative tradition – these monographs are, at times, equally in danger of offering an opaque view of the British graphic design landscape.

The need to align one’s work with either a modern or traditionalist approach, or to take sides with abstraction over naturalism, was never an issue for Eric Ravilious and Edward Bawden. Working across a diverse range of forms, they generated a graphic idiom that maintained a connection to the long established traditions of the applied artist and craftsman. As Brian Webb notes in the newly expanded edition of Design, a small but wonderfully illustrated book documenting the life and work of these two figures, ‘they invented patterns to suit the given brief, whether realistic, fantastic or pure; these were just vital variations of the artist-designer’s rich visual language.’ The outcome was a style that has since become synonymous with the decades between World War I and II, and consequently impacted upon the look of the 1951 Festival of Britain.

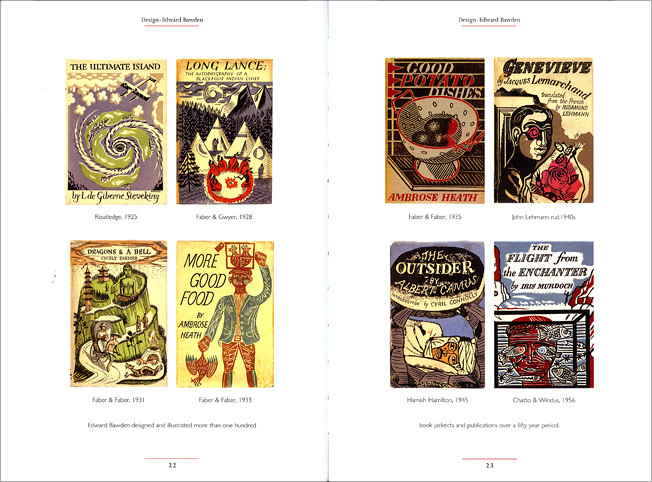

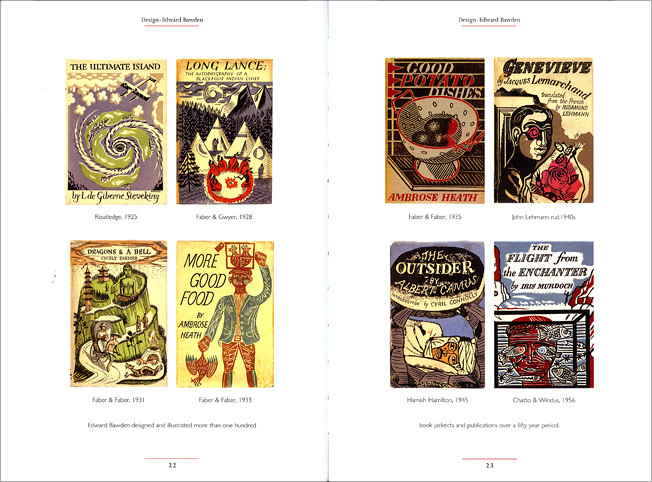

Design serves to acknowledge the common artistic heritage of Ravilious and Bawden by allowing the illustrations to flow into one another. Forgoing any significant chapter break, Bawden’s evocative book jackets and woodcuts blend seamlessly into Ravilious’s posters and famous alphabet china designs for Wedgwood. As Webb reveals, the origins of this shared approach originated at the Royal College of Art, where both studied in the early 1920s under such tutors as Paul Nash, Edward Johnston and Harold Stabler. Becoming firm friends, Bawden looked to specialise in book illustration, while Ravilious focused initially on murals. In what was to be one of only a handful of collaborations, it was during this time that their shared visions came together in the production of two RCA student magazines. Published in 1925, Gallimaufry saw Ravilious manufacture some evocative illustrations, with Bawden contributing several coloured drawings; one year later Bawden produced a raucous cover illustration for The Mandrake, with Ravilious crafting the title page engraving.

While 1928 saw Bawden and Ravilious collaborate on a fantastical mural for Morley College, South London, the 1930s found these artist-designers directing their attention towards the projects which would cement their respective reputations. Bawden manufactured his delightfully illustrated wallpapers, posters and book designs (of which he eventually produced more than 100); while Ravilious produced his now famous engravings for Twelfth Night, published by the Golden Cockerel Press, and his coronation mug creations. As we know, Ravilious’s life was cut short in 1942 when, aged only 39, he died during an air-sea rescue mission over Iceland. Bawden died aged 80 in 1989. In Design the contrasting durations of these lives clearly gives Bawden’s work a sense of completion, the feeling of a sustained development over his long life. Yet, the strength and originality of Ravilious’s work belies the brevity of his professional existence. While he lived twice as long as his friend, Bawden’s designs and illustrations frequently equalled, but rarely surpassed, those of Ravilious. In essence, for both, the 1930s served as the high water mark of their creative well. It simply came about that Bawden continued to draw on this rich source for an additional half a century.

Bawden and Ravilious’s ouput has rightly come to signify the life of the resourceful and efficient artist-designer. The diversity of their creations reveals the imagination of the painter expressed through the technical knowledge of the printmaker. While limited in size, this book underlines the enduring quality of the works that resulted from this union between vision and craft.

Cover from Design: Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious by Brian Webb and Peyton Skipworth.

Top: Spread showing works by Edward Bawden.

Kerry William Purcell, design historian, London

First published in Eye no. 60 vol. 15, 2006

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.