Summer 2008

Art direction unknown

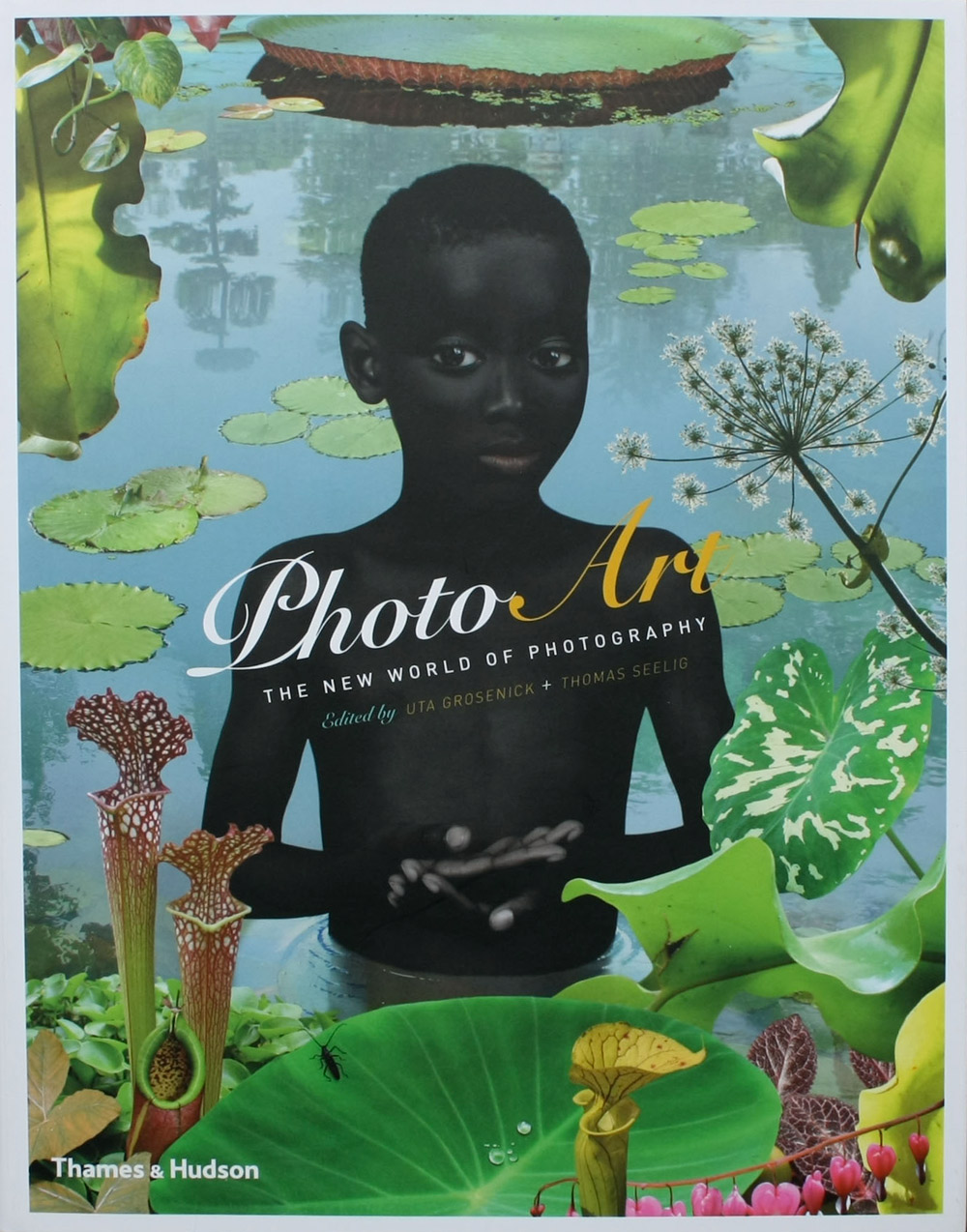

Photo Art: The New World of Photography

Edited by Uta Grosenick and Thomas Seelig<br>Thames & Hudson, £24.95<br>

What makes a photo art? It helps if you encounter it in some sanctioned art-viewing space, a big white room or a converted slaughterhouse. In a book, or on the street, or on the internet, boundaries are less clear. Most of the photographic images we encounter in our lives are intended to communicate data about the real world to us, or to sell us things. The fact that they do so by pleasing our senses, or informing us, or making us think, or putting a smile on our faces – by doing what ‘art’ in most media aims to do, in short – doesn’t mean we should discard a certain scepticism, not just about how a certain image was generated or what relation it bears to ‘reality’ (which in this context merely means what we would have seen if we’d been present when the photo was taken) but more about the elementary question of what the image is for.

This book collates work by mostly youngish photographers – and, notably, collectives of photographers – from around the world. It is impressively, though also a little perplexingly, diverse in subject, technique, style and tone. The old academic distinctions of genre – portrait, landscape and so on – are only occasionally relevant – though, for what it’s worth, landscape seems quite big at the moment, maybe because ecological anxieties are prominent across the rich world. The kind of wild digital manipulation that was common a couple of years ago seems to be on the wane (Wangechi Mutu’s bizarre anatomical collages are made the old-fashioned way, with a scalpel and some glue), or increasingly reserved for work that aims at an overtly fantastical or magic-realist quality, such as Ruud van Empel’s disconcerting images of children in Rousseau-esque, composed landscapes.

Several pictures in the collection bear the stamp of slightly older, better established photographers; there is a lot here that reminded me of Andreas Gursky and Wolfgang Tillmans, to cite a couple of examples. There is also plenty of more conscious or even combative imitation (the artspeak term is ‘referencing’), from Qingsong Wang’s version of a famous Renaissance double portrait to Jean-Luc Moulene’s ‘Girls of Amsterdam’, a series of images of prostitutes that takes Hannah Wilke’s feminist appropriation of a stock pose from conventional heterosexual pornography and, as it were, de-appropriates it. These pictures, incidentally, lose a lot by being reduced in size for publication, as must many others; photo art in a gallery tends to proclaim its credentials by territorial means: that is, by being big.

But what makes these photos impeccably ‘arty’ is what tends to undermine them as art: namely, a preoccupation with style. It is striking how fluid the careers of many contributors are, how easily they hop between gallery commissions and commercial work. This is fine, of course, and a girl or boy’s got to make a living. But there is an easy, even glib, acceptance of conventions of style on show here, from the polished monumentality of Tacita Dean to the murky sublimity of Richard Billingham’s coastal landscape, to the icky surrealism of Diana Scheunemann’s masked masturbators. There is art – and then there’s art direction.

Top: Cover for Photo Art: The New World of Photography.

First published in Eye no. 68 vol. 17 2008

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.