Summer 2016

Automonography

Abbott Miller

Pentagram

Kim Walker

Book design

Graphic design

Reviews

Typography

Visual culture

Abbott Miller: Design and Content

With essays by Ellen Lupton and Abbott Miller. Foreword by Rick Poynor<br> Designed by Abbott Miller and Kim Walker, Pentagram, New York<br> Princeton University Press, $60, £40<br>

Abbott Miller’s book tells the story of a life in design: starting out – as his wife and early collaborator Ellen Lupton saw him – exuding an ‘excruciating innocence’ that ‘begged to be roughed up’, Miller became a brilliant independent, setting new standards for ‘design authorship’, and eventually joining Pentagram as a partner (see Eye 45). This book is not so much a monograph as an autobiography, written mostly in the first person singular, and including some articles originally written for Eye and elsewhere. However I fear that the title, Design and Content, perpetuates a creaky dualism that undersells design – especially the luminous examples shown here.

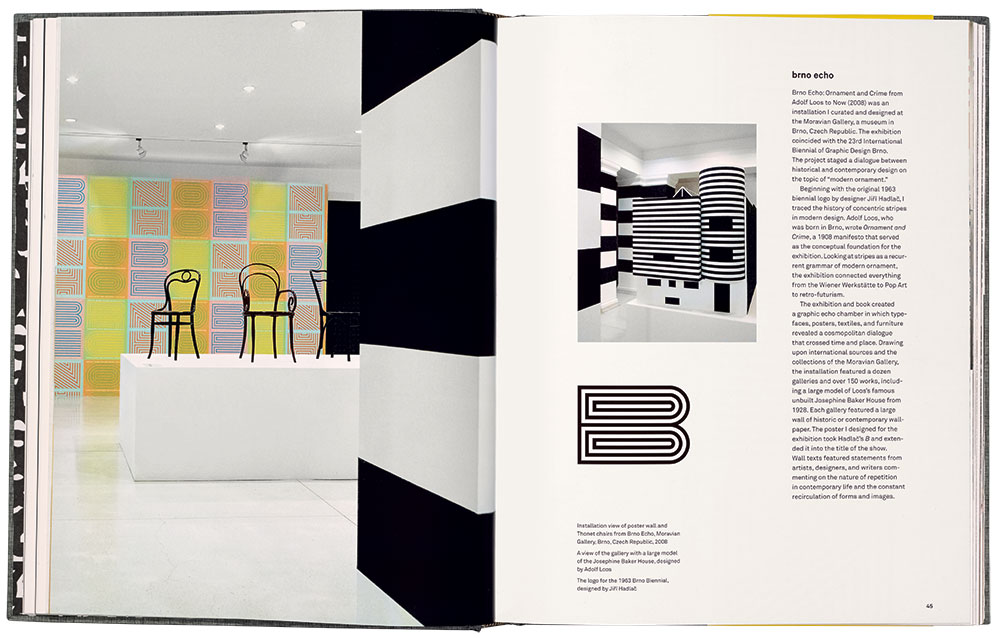

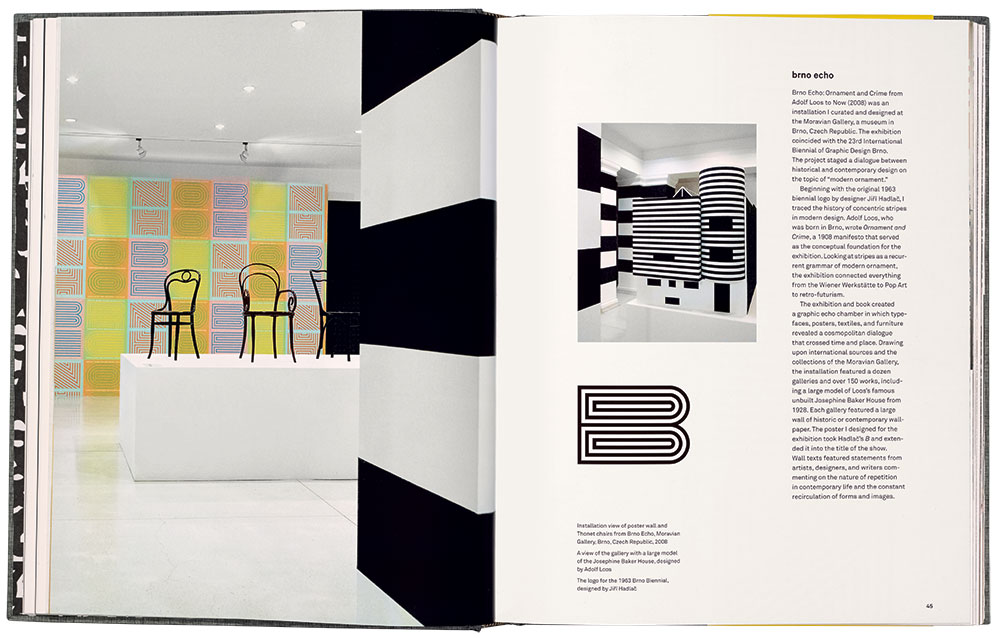

One example in the book that demonstrates that ‘design and content’ need not be separate entities – that design is content – was Miller’s 2008 installation ‘Brno Echo: Ornament and Crime from Adolf Loos to Now’, which he curated and designed for the Moravian Gallery in Brno, Czech Republic. He took a formal aspect of graphic design, concentric stripes, and presented its rhyming recurrence across many design disciplines. It is in projects like this, driven directly by the visual material, that his design work breaks new ground.

One of the most impressive passages in the monograph charts Miller’s virtuoso path as an editorial designer through the world of artistic performance: from its genesis in [the recently revived] Dance Ink magazine; to work for the fashion designer. Geoffrey Beene and 2wice magazine; to his Guggenheim catalogues for Matthew Barney’s The Cremaster Cycle; a Robert Morris retrospective; and a book about cabaret artist John Kelly. Two chapters are dedicated to a visual essay about his education in dance and visual performing arts, and the way he learned to fuse design and content in one role, as exemplified by 2wice. Here he recasts the visual-material subject at hand – not merely presenting it reverentially – as a museum curator might.

In his book designs, Miller makes clever use of structure to organise visual and text material in ways that serve to make more explicit visual attributes of the book’s subject matter. His ingenious typographic solution for positioning the text in the book Antonin Artaud: Works on Paper (1996) places the original text and its translation in a Rorschach-like symmetry. When it comes to letterforms themselves, Miller is more adventurous in three dimensions than in two-dimensional print: witness his touring exhibition of Rolling Stone covers (1998), the photo project Village Works (1999) and the supernatural 3D renderings in Dimensional Typography (1996).

In his design for ‘The Couch’ (2006), an exhibition in a preserved room above the Sigmund Freud Museum in Vienna, Miller inserted a raised false floor and then cut apertures into it to reveal the original parquet floor, creating a kind of inverted plinth for the exhibits. I have never seen all the lighting fitted under the floor in an exhibition before; the illumination emitted from the cut edge of the floor expressed the division between the installation design and the original space. Hanging down from the ceiling of the apartment and winding sinuously through walls from room to room was a most beautiful wayfinding device, a fine typographic ornament cut out of opaque and glossy black acrylic sheet, inspired by a botanical motif found in the apartment. There is no need for words or even symbols: here the design is the content, so splendid is the synthesis.

But to return to Miller’s title – might the graphic designer’s customary reverential tone regarding ‘content’ have something to do with the lack of a proper research tradition in graphic design? Is ‘content’ a symptom of the deep-seated intellectual inferiority the discipline can’t yet shake off? Miller writes in the introduction: ‘Design is not a passive presentation of already cooked and digested ideas, but a critical tool, capable of creating its own insights.’ But even here there is the sense that the highest achievement any piece of design can hope for is the creation of ‘content’.

A monograph about a graphic designer is often made by the same designer – an automonography. Miller has put together a fine book about himself but it would be even more fascinating to read a book about him by someone else, designed by someone else. His work deserves it.

Top and right: cover and spread from Design and Content showing installation views of ‘Brno Echo: Ornament and Crime from Adolf Loos to Now’ at the Moravian Gallery, Brno, 2008, curated and designed by Abbott Miller / Pentagram. Book design: Abbott Miller and Kim Walker, Pentagram.

Nick Bell, designer, former Eye creative director, London

First published in Eye no. 92 vol. 23, 2016

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published quarterly for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues. You can see what Eye 92 looks like at Eye before You Buy on Vimeo.