Summer 2021

Captain litho

Barnett Freedman

Adrian Hunt

Design history

Graphic design

Illustration

Posters

Reviews

Barnett Freedman: Designs for Modern Britain

Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, UK14 March – 1 November 2020. Curator: Emma Mason, Catalogue: Barnett Freedman: Designs for Modern Britain, £24.95.

Barnett Freedman (1901-56) was an artist / designer from a Jewish immigrant family who grasped the technology of his time and made it his own. Freedman’s auto-lithographs conjure a spirit of mid-century Englishness with such warm familiarity that it is easy to forget how non-establishment he was – the designer of the King’s Golden Jubilee stamp (1935) whose own parents had arrived from Russia a few years before he was born. Freedman’s early years and youth were marked by ill health and poverty, but he nevertheless acquired a substantial education, together with a gift for leadership and skills in music, drama and art. His fellow students nicknamed him ‘Soc’, short for Socrates. At the height of his career, printers called him ‘Captain’ …

Barnett Freedman’s melancholy cover and spine for the first edition of Memoirs of an Infantry Officer (1930) by Siegfried Sassoon.

Top. The Darts Champion (1956) is one of Freedman’s last works, a Guinness lithograph that shows its subject from the point of view of a pub darts board.

Although he struggled to get by in his twenties, by the mid-1930s he had acquired such a reputation for creativity and technical ingenuity that it ensured a steady stream of paying clients, including Faber, Shell-Mex and the GPO (Post Office). When the war came, he applied his talents to vigorous drawings of ships, seamen and submarines that stand comfortably alongside similar images by better known contemporaries and friends, such as Eric Ravilious, Edward Bawden and his former RCA tutor, Paul Nash.

After an opening splash that includes a pair of nine-colour London Underground posters (from the collection of Paul and Karen Rennie) the exhibition ‘Barnett Freedman: Designs for Modern Britain’ at Chichester’s magnificent Pallant House Gallery displayed his work in largely chronological order through several rooms. Early paintings show his gifts for character and atmosphere, but the works spring to life when applied to sympathetic commissions.

His illustrations for Siegfried Sassoon’s Memoirs of an Infantry Officer (1930-31) gave him a wider audience, and his cardboard ‘peepshow’ (1932) for Shell, showing winter and summer scenes, revealed an ingenious command of print and paper. His increasing range as an image-maker went hand in hand with his mastery of the means of its reproduction.

Freedman’s Silver Jubilee stamp design, 1935, the subject of The King’s Stamp a short documentary produced by Alberto Cavalcanti and directed by William Coldstream for the GPO Film Unit with music by Benjamin Britten.

The catalogue includes three selections from Freedman’s own writing. In ‘Auto-Lithography or Substitute Works of Art’ (published in The Penrose Annual in 1950), he calls for better printed books and makes a fiery denunciation of poor printing, in particular the deadening ‘interminable dot of the photo-mechanical screen printed on shiny or coated paper giving them that dreadful appearance which completely ruins a book.’ Freedman saw auto-lithography (in which ‘auto’ means authorship) as an opportunity for the designer to take control of his work and its reproduction. ‘Nothing is lost; colours retain their brilliance and transparency.’ (The catalogue, printed on rather shiny coated paper, doesn’t quite do justice to Freedman’s luminescent lithographs.)

Compared to his oil paintings, Freedman’s prints are more colourful, and his book illustrations (for classics such as Oliver Twist, War and Peace and Jane Eyre) are infused with the theatricality of his posters. Yet his most affecting pictures often feature regular men and women, like the Personnel of an Aircraft Factory (1942), the cast in his publicity materials for the wartime film San Demetrio London (1943) and Headquarters Room (1944). The Darts Champion (1956), made for the Irish brewer Guinness, is a bullseye’s view of a smart, sharp young dart-thrower.

The catalogue also includes an abridged version of a chapter written by Michael Twyman for the Fleece Press’s limited-edition Barnett Freedman: The Graphic Art. Twyman points out the ‘discipline in planning and mark-making’ required by Freedman’s approach to lithography, which cannot be done in what Freedman called ‘a nice studio in the quiet company’. The artist argued that he must ‘become entirely immersed in the whole gamut of production, finding out for himself, by experiment and failure, all about paper, ink, the temperature of the printing works, as well as “temperament” of the machine minder and the printing works manager!’

Freedman’s litho stone drawings in ‘Barnett Freedman: Designs for Modern Britain’, Pallant House 2020.

Freedman’s wartime work included Interior of a Submarine, which gives urgent purpose to both men and machines, and a series of sensitive portraits of the 60 crew members of the submarine Tribune – both watercolours with pen and ink made in 1943. These dignified portrayals of working men, like the similarly good-humoured pictures of civilian factory workers and the officers of HMS Repulse, demonstrate Freedman’s talent for reportage, showing character through lines and cross-hatchings that capture the body language and facial expressions of a multitude of individuals.

Freedman sought to depict people doing their jobs, and his months on board the Tribune gave him a unique opportunity: ‘Here was this submarine – this great machine – filled with machines; simple elemental machines like huge lumps of iron – complicated and elaborate machines with biased gears and eccentric wheels; and very sensitive delicate machines – the gyro-compass – marvellous to see.’ Freedman described this experience in a BBC radio broadcast made shortly after the war ended in Europe. He said: ‘If you see a man turning a wheel, you can tell immediately whether he cares for machines or not.’

Freedman was an artist who understood machines. His wartime submarine experiences clearly resonated with his own commitment to finishing a job by going ‘on press’.

John L. Walters, editor of Eye, London

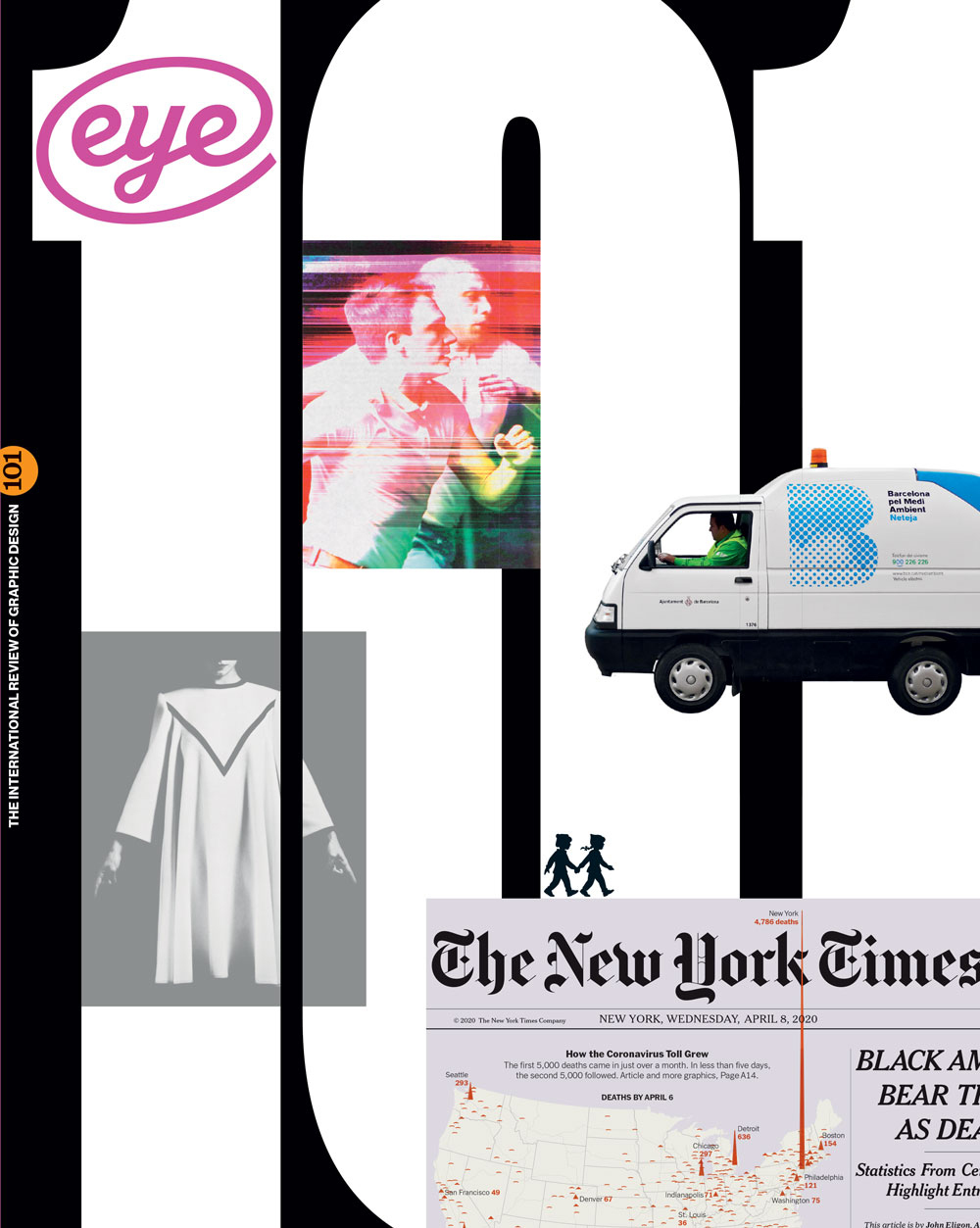

First published in Eye no. 101 vol. 26, 2021

Eye is the world’s most beautiful and collectable graphic design journal, published for professional designers, students and anyone interested in critical, informed writing about graphic design and visual culture. It is available from all good design bookshops and online at the Eye shop, where you can buy subscriptions and single issues.